“THE LAW OF RIPOLIN”: the words greet me even before entering the Kunstkredit Basel-Stadt 2017 group exhibition where Garrett Nelson’s ‘Pique his Vanity’ installation is displayed from August 29 to September 3. The large capital letters are woven on a black carpet hanging opposite the entrance of a room at Kunsthalle Basel. Below, a white curved shape is represented. It is a protection cup – the plastic device used by male athletes to shield their ‘manhood’ from painful shocks.

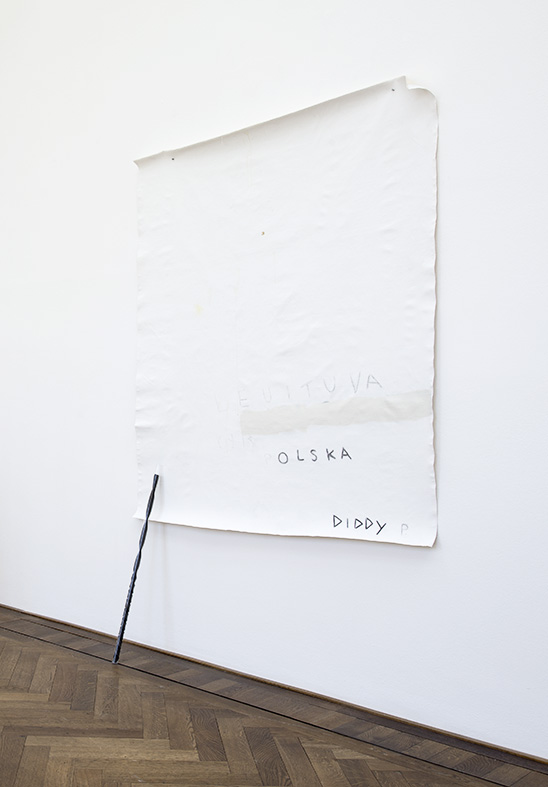

The Berlin and Mexico City-based artist’s project spans an entire room, through various objects and media. It is composed of – in addition to the rug – a black marble, slightly oversized replica of another modern codpiece under a Plexiglass box on a pedestal, a white canvas with barely legible inscriptions and markings and a video work showing three performers declaiming a text by the artist, while interacting with their architectural surroundings.

Looking back at the words on the suspended fabric, I recognise a quote from the 1925 text The decorative art of today by Le Corbusier declaring that ornamentation should be banned from modern homes and “replaced with a plain coat of white Ripolin.” The architect substituted adornment with a bare, white interior as a means of achieving the necessary purification for people to enter the modern age. The first ever commercialised enamel paint, with its ability to cover a surface with a resistant and hard coat of glossy white, was thus, in Le Corbusier’s discourse, a factor and guarantee of purity, not only of the architectonic space, but also of its inhabitants’ minds.

Garrett Nelson’s reference to the modernist pioneer’s words is a provocation. Embedding a quote from the apostle of industrial design in a handcrafted object appears as a direct challenge to his gospel. It mocks the idea of what Le Corbusier called ‘productive morality’ as a prerequisite for a new society, and in particular the fantasy that it could be achieved with a simple coat of bloodless paint. What’s more, the motif of the protection cup is used, in Nelson’s own words, as an allusion to the vulnerability of the male ego. What looks like an empty shell is here ostensibly referring to masculinity by reducing it to the fragility of a man’s genitals. One cannot help but look at the association of the quote with this giant depiction of the motif as an ironic allusion to Le Corbusier’s reputed misogyny.

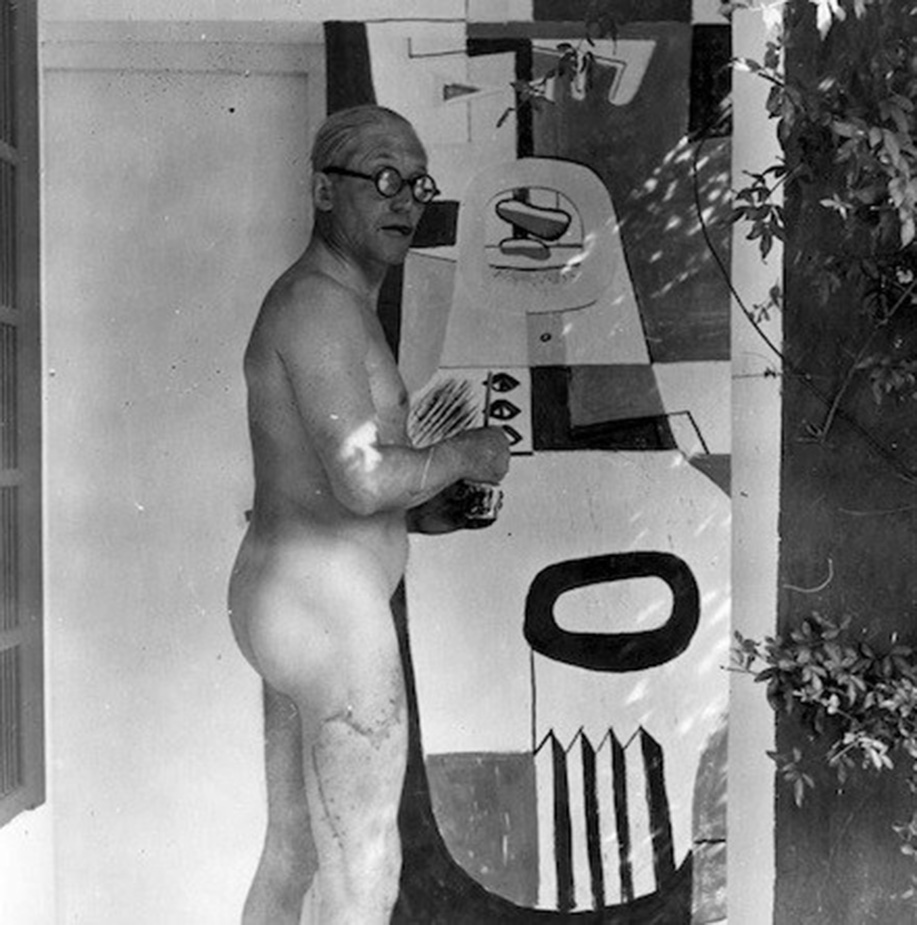

That’s when I remembered this peculiar photograph of the architect in the nude. He is standing in profile, brush in one hand and paint can in the other. His face is turned towards the camera with a look of surprise, or is it defiance? He is painting on a façade. On Le Corbusier’s naked body, a huge scar is visible. It is the summer 1938; he is spending holidays at the E-1027 house, an enchanting modernist villa on the Côte d’Azur, property of Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici. The Irish furniture designer, founder of a successful carpet-weaving workshop, and the French architect had designed this house together as their love nest a decade earlier in what would remain their only collaboration. At the time of the photograph however, the couple had already separated, and Le Corbusier and his wife Yvonne were staying with Badovici. The nasty scar on Le Corbusier’s right thigh is a few days old. While swimming in the sea, the architect was hit by a boat and seriously injured by the propeller. But more critical in the tale than his accident is that during his stay, Le Corbusier painted eight murals on the walls of the E-1027 house. Gray called it an “act of vandalism” and considered it an affront to her architecture. Despite her requests, Le Corbusier never removed his frescoes. He even photographed them and published a book in 1949, where he intentionally omitted the fact that the house was Eileen Gray’s design, simply stating that his murals “burst out from dull, sad walls where nothing is happening.”

It is said that Le Corbusier was obsessed with the E-1027 house, perhaps even jealous of such an achievement of modernist architecture. Although he tried to purchase the villa, he never succeeded and resolved to build a vacation cabin right next to the object of his desires and envy. What he managed to do, however, was to take credit for the house through frequent mistaken attribution at the expense of recognition for what was the work of another person, a woman. Calling it like it is, Le Corbusier’s ‘burst of creativity’ on the walls of this house represents a gesture of misogynist vengeance and physical abduction of Eileen Gray’s success. His ego was piqued by Gray’s mastering of modernist vocabulary, so he reacted by coldly humiliating her and sabotaging her work in a spectacular territorial gesture.

Enshrined like a devotional object, the second protective shield in Nelson’s installation, carved in black marble, furthers this thread of a caustic critique of the modern male figure. The three breathing holes of the cup make up a face, a ghost with an expression of surprise at its own futility and sacralisation. What’s more, the sculpture also refers to modern aesthetics and its search for formal purity through essential shapes. Just as Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse epitomised an entire body through the abstracted representation of a single head, Nelson’s stone codpiece brings into play an ambiguity between the masculine presence suggested through the shape and the absence of actual human body parts. It thus enters the realm of suggestive power, while questioning the symbolism behind the object. It is as if the object was lying there to claim the obsolescence of masculinity as constructed myth by staging the emptiness of its exaggerated curves.

In looking at Nelson’s ‘Pique His Vanity’ in light of Le Corbusier’s destructive E-1027 anecdote, not only does the work become an explicit critique of a certain modernist ideology, but also an unintentional homage to the figure of Eileen Gray and her achievements as an architect and designer. Gray’s views on Modernism were radically different from Le Corbusier’s. She famously criticised her fellow architect’s concept of machine à habiter by saying, “A house is not a machine to live in. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his emanation.” Opposed to Le Corbusier’s determinist ideology of modern homes as purified places to morally shape citizens, Gray’s understanding of Modernism was that a building had an essence, which should organically match both its physical surroundings and the inhabitants’ mind. When asked about the white canvas hanging in his installation, Nelson told me it is the replica of a prison cell wall. It is painted white: rational, neutral, pure, moral. Ripolin? The inscriptions on the canvas make no sense. Looking at them, one simply feels an urge, the urge to express something, anything, to leave a trace, but also to provoke, to defy authority. With no pencils available in jail, inmates use whatever they can: cigarette butts, bodily fluids, sharpened objects, to scratch the paint from the wall. From this collective act of subversion, an incidental fresco emerges. It is an anonymous work of art, and at the same time it is an act of rebellion, a rebellion against the patronizing system and its morals.

A simple stroke or a scratch on the clean surface suffices for the illusion of purity associated with white walls to be shattered. Le Corbusier himself knew it and it is precisely the strategy he resorted to while vandalising Gray’s house. Although both architects had opposing views on the purpose of architecture, white was nevertheless as fundamental in the E-1027 house as in “The Law of Ripolin.” What both architects were disagreeing on was in fact the function of Modernism. Thus, when Gray criticised Le Corbusier’s machine to live in, it was not the modernist architecture as such that she was condemning. Rather, it was the moralising myth imposed through his authoritarian discourses that she found objectionable. When applied to the working class, modernist dwelling units can indeed become like prison cells. It is no longer the pomposity of a beautiful villa, garishly displaying its white walls as the claim for a new lifestyle. It is the standardisation of housing and the totalitarian utopia of a machinist society that consciously alienates individuals. While it would certainly be unfair to minimise the importance of Le Corbusier’s contribution to the practice of architecture, it is true that his mechanistic vision was problematic for its treatment of people. In his writings, architecture becomes at times so distant from humans that it turns into a shell as empty as the protection cups in Nelson’s installation.

It’s this oppressive purity that the video work in ‘Pique His Vanity’ challenges. Three models wander around a stage of architectural surroundings. The trained eye will recognise iconic Berlin buildings: the Luckhardt-Villa/Haus am Rupperhorn by the Luckhardt brothers, the Unité d’Habitation/Corbusierhaus and the Kreuzberg Tower by John Hejduk. The spoken text, a poem perhaps – “when measuring / the length of / your penis / please push / ruler firmly / against the / pelvic bone” – is at times being recited by the actors, or read by a voice-over. The actors move around the buildings and pose – reclining over a balcony, mimicking a radiator through a window or embracing a protruding gutter – interacting with the different buildings composing the stage of this bizarre choreography. It almost seems like a sensual dance where the characters are engaging in a form of sex with the architecture, celebrating it and bringing humanity into the cold concrete frame.

A coat of whitewash, the “moral act of purification,” will always cover up the traces of vandalism and tame the insubordination to oppressive discourses. A deeper act of resistance is necessary. In this regard, Nelson’s video is like a symbolic ritual of liberation from the tyranny of Ripolin. It stages a softer act of rebellion. It is a ceremonial way to break the curse of the dominant narrative that influenced modern housing, and culture, under the premise that architecture should become an engine for influencing its occupants. An answer to the architect’s writing in “The Law of Ripolin” (“Whitewash is extremely moral”), the text is a succession of short aphorisms celebrating the human in its complexity, ugliness, impurity and multifaceted nature. It is about sex, anxiety, love, loneliness and community, queerness and beauty. It is humanity against the machine-man and joy against obscurantism. Most of all, it reminds us – at the time of renegotiating notions of identity, gender and race – of the importance of freeing ourselves from the stranglehold of the deterministic discourse that shaped modern society. There are still too many ‘Le Corbusiers’ out there, taking advantage of their privileged position to oppress and dominate, claiming credit for what is not theirs and their peers. It is only by encouraging disruptive actions and discourses and celebrating diversity that we can hope to finally overcome the discriminatory Law of Ripolin. A building is not moral, nor is a colour.**