From a shared can of beer in the twilight of London rave culture to a tragedy at a corporate rave in gentrified Shoreditch years later, Iphgenia Baal’s third book, Merced Es Benz narrates the arc of a doomed relationship. For anyone who found love in an online chat window or was tantalized by the possibilities of its ecstatic immediacy during the early days of social media, the format will undoubtedly be familiar. Pieced together from fragmented Facebook conversations, the novel published by Book Works in March 2017 is an epistolary novel that relies on the ephemeral messages sent from parties, buses and bedrooms to reconstruct hazy personal histories. Punctuated by distance, silence and cruel romantic games, Merced Es Benz ultimately shows the fragility of our online lives, and the difficulty in making sense of our entanglements through the scraps of ourselves we leave behind on the web.

It’s significant then that Iphgenia and I speak over Skype, followed by more emails and collaborative edits. The first conversation gets off to a glitchy start, while I struggle to get the camera on my laptop working and set up the recording. “Sometimes it’s better just to use a tape recorder,” Baal suggests jokingly before everything finally gets going. It’s late afternoon in London, and the darkness is creeping into her apartment, a stark contrast from the lazy Saturday morning sunshine in Los Angeles. In our hour-long call, it becomes clear that the author possesses an unshakeable DIY attitude, and a commitment to approaching her literature — and her life — without compromise.

Set against a wealthy London clique who dominate the art, music and real estate scenes, Merced Es Benz gives an intimate insight into a floundering relationship that is collapsing under the pressures of drug addiction, shady secrets, misleading online personas, and the slipperiness of online communication. As the two protagonists flit across London and the world, falling in and out of sync with each other, ultimately the struggle to keep up with a privileged party crew reaches its inevitable conclusion.

Perhaps most importantly of all, in a world where heroin dependence is a minor medical issue for the rich, but a moral failing for the rest, the book works to preserve the legacy of a relationship that has been corrupted by the clichés and judgments that inevitably accompany addiction. Emerging from the midst of London’s flagging alternative culture, Merced Es Benz embraces the possibility of love no matter what the cost, and grapples with the consequences of refusing to conform.

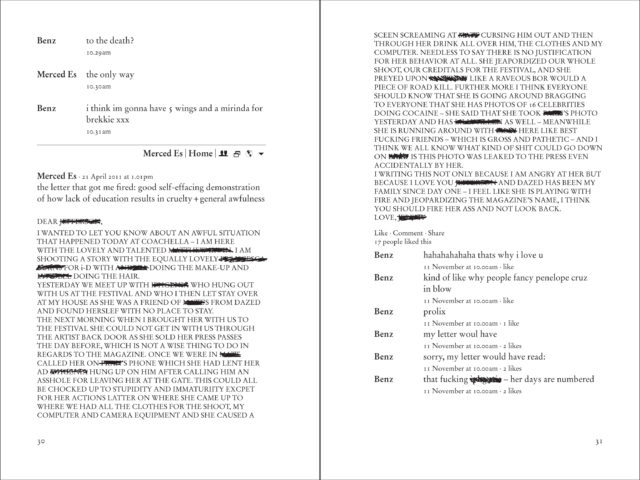

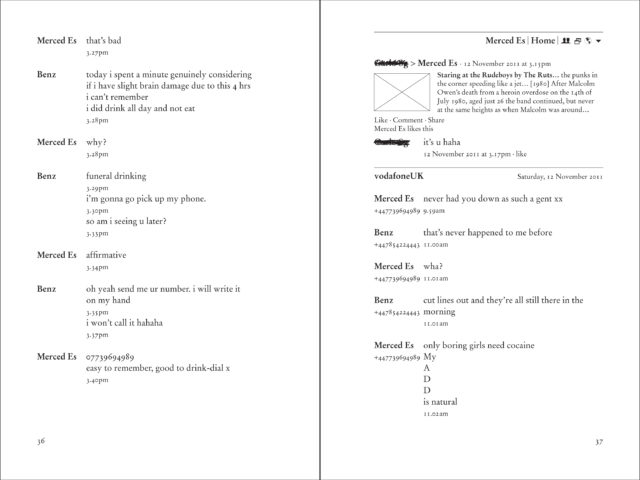

Like Baal’s previous work, there is a visual element to the writing process, with other media forms incorporated into the design of the book. This strange copy-paste technique, full of redactions, phone numbers and timestamps, gives an urgency to the events that would be lost with a more traditional approach, and gives additional weight to what goes unsaid.

** How much of your relationship with BT in Merced Es Benz is fictionalized?

Iphgenia Baal: It’s all fiction, insofar as the act of writing something down requires omitting 99 per cent of reality in order for it make sense, but since a lot of the relationship was written in the first place — we spoke as much over Facebook and in texts as we did face to face, so the ‘fiction’ was built in. It wasn’t two people talking, it was two personas interacting, a phenomenon exaggerated (if not caused entirely by) Internet and telephones. The conversations [included in the book] are like clues, evidence of real people and real events, but who the people are and what actually happened remains unclear.

** Was it tough to go back and revisit some of the experiences you chose to include?

IB: Not really. I mean, the first messages I read after [BT] died were the ones we’d sent on facefuck, mainly because the conversations didn’t take much finding, they were just there. The first conversations I read were some of the last conversations we’d had, mostly empty threats and desperate sounding messages. Reading those made me cringe, but months later I found a load of texts on an old Blackberry and when I read those, I didn’t recognise myself at all. I suppose I approached them in the same way a very nosey stranger would. And what I found, or maybe constructed, was this spooky subtext—pretty death-obsessed. Also, the constant miscommunication: messages sent without previous messages being read properly or at all… plus the lazy assumptions people make. Like, if you post a picture of yourself at the beach, everyone assumes you’re at the beach, when you could be anywhere. Things like that can be a mistake, or done on purpose, but in the end have the same effect. I mean, maybe it’s a trite example, but when you add it all up, it totals a deluge of misinformation… why our communication these days is so frayed and basically fucked.

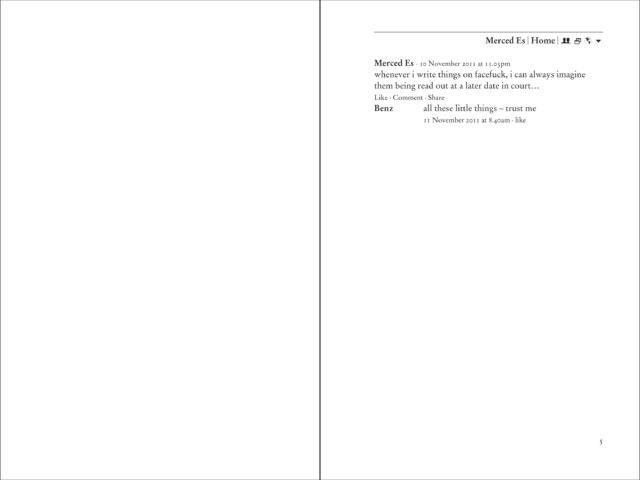

** The first line in Merced Ez Benz reads, “Whenever I write things on Facefuck, I can always imagine them being read out at a later date in court…” Can you talk a little bit about that?

IB: It was, amusingly, the first interaction Merced Es and Benz had online. Other than that, the sentence works as a pretty smart modernisation of the old ‘publish and be damned.’ So, it’s a disclaimer. The idea that simply stating an idea is enough to offend people has always tickled me, but then what with all the online shenanigans these days, the ‘burn the witch’ mood in society is heightened to a tiresome degree. People love a lynch mob, which is in fact what I was writing about in The Hardy Tree—A Story about Gang Mentality. It’s not the gang mentality people assume—drugs and dealers and guns and stuff. More people grouping together, towing the line…

** In Merced Es Benz and The Hardy Tree the climax occurs at a rave. Did you grow up in rave culture?

IB: I went to squat parties when I was a kid but, as people never tire of telling me, I’m too young to really remember rave culture. It belongs to the generation before mine, so all the free-party-living-in-a-trailer-M25, blah blah blah, was ultra-mythologized for my lot, because it was the thing we’d missed. But look at London now—that whole culture is dead. It’s been suppressed completely. Not just squat parties, but the whole mentality of feeling like you owned your city. Only yesterday I got fooled into going to a bar in Dalston and as soon as I walked in I thought, ‘What the hell is going on?’ It’s so boring. The music is shit, the music is quiet, the décor is bad, the drinks are expensive and everyone’s dressed up. I dunno, I looked around and just thought, ‘you lot have no fucking idea…’

I only realised recently that The Hardy Tree and Merced Es Benz not only have the same sort of structure, but also conclude in the same sort of way and I think it’s just because, for me, raves were always the most romantic, they were where stuff happened. And now, no more, so yeah—lighter in the air at an emo gig—RIP the rave. Goodbye.

** What are your thoughts on ‘counterculture’? Does it exist anymore?

IB: The current consensus seems to be that counterculture is dead. I mean, I’ve heard it enough times, but I think there are always going to be too many people to catalogue who aren’t willing to do what they’re told, but I think these days it’s more difficult to find evidence of them. Maybe one aspect of today’s counterculture is that it wants to be incognito, in protest at the rest of culture’s constant thrust to promote.

** I’m interested in the format of this book. There have been a few books lately that pursue an epistolary style that use email or text message, but yours is one of few that I know of that derives its material from Facebook.

IB: I think a lot of the reason why people don’t admit to using Facebook or don’t use it as content is because it’s lame. Also, it’s a more recognisable brand than email or text, even if these are also delivered by specific carriers, but for some reason it’s less immediately obvious.

** Your books tend to include a lot of visual elements. There’s a piece online, one where you’ve written inside a phone bill. Or in The Hardy Tree, which pieces together the story of Thomas Hardy’s ‘Resurrection Men’ who cleared gravestones in St. Pancras to make way for the railway with newspaper cuttings, handwritten letters and other documents…

IB: The Hardy Tree is the only book I wrote in Word, because it was before I learnt InDesign, which has now become what I write in. I used to write in-house for a magazine and found the best way to edit text was by giving it to the design department, who’d say, it needs it to be five lines longer or three lines shorter and I’d hack at it accordingly. It made me less precious about what I’d written. Like, if something’s got to go, it’s got to go. Plus, I like having different processes. If I just write, I go mad and design without content is dull.

I guess I’m begrudgingly learning to be more professional—I’ve always been decidedly anti-professional and highly suspicious of professionalism, mainly because I remember reading books when I was younger and thinking, ‘How could I ever do that?’ But what I later came to realize was that this idea of the ‘great author,’ the ‘exceptional individual,’ is a myth. Almost all cultural produce, books included, goes through countless stages of editing and making, usually by multiple people. Weirdly, I think it is in these stages where the cost or worth of a book is defined, rather the actual writing. The creative… or the entertainment industries, whatever you want to call them, professionals seem to radiate a sentiment of ‘We are the ones who know what we’re doing, you’re a moron, so buy the book and shut the fuck up.’ So, I’ve always liked the idea of being unprofessional as in opposition to that, but I suppose in the end, being professional is just knowing what you’re doing, which sometimes means knowing that the right thing to do is to let someone else do it.

** Do you think people’s accessibility to other people’s thoughts and rants on social media has made this fragmentary style of writing more acceptable when packaged?

IB: I can’t speak for anybody else, but I love bad writing as much as I love the rants of lunatics. Most people accept whatever, as long as it is presented in the right context. The wrong context, or confusing them, can provoke all sorts of reactions, but mostly being totally ignored. Course this can be played with. People have certain expectations of books, the same way people have certain expectations of screens—but imagine trying to make someone log into your Facebook and force them to scroll back for months and then read all your boring shit… I mean, it’s not gonna happen, but in a way that’s all Merced Es Benz is.

**[Spoiler] In the first chapter of Merced Es Benz, BT has died basically, but then you lead with a conversation between the two of you. There are these long gaps where he doesn’t respond. It’s almost like he has already died in a way. You just keep talking and there’s no response.

IB: BT wanted to be wanted and he was very aware that not responding to people was an effective tactic, but Merced Es Benz is a dual narrative. His narrative might seem the dominant one—a story about this crazy, crazy guy, clever, amazing, fucking lunatic bastard on a death trip, but the other part, the female narrative is not some meek, long-suffering… she’s a menace. I guess I was trying to out myself. I mean, it sounds stupid, but after BT died I briefly entertained the idea that I’d texted him to death. But no, at its core, whatever else is going on, it is two people who refuse to do what they’re told—maybe a decent example of the sort of counterculture I was talking about earlier. People who won’t accept what’s given to them and who’ll break even useful rules on principle.

** Jumping to the end of the book, explain the tabloid material.

IB: The first draft of Merced Es Benz was an edited version of a series of private conversations without explanation, but as the idea of publishing the text became more real and I started to think about how to make it not only make sense to someone else, but to mean something to someone else—death is cheap in fiction, the inclusion of the hack journalism worked as shorthand for the shitty state of culture.

Summing up [BT’s] life as ‘Mick Jagger’s son’s friend’ is so crass. But I mean fuck, it’s not like BT is the only victim of this shit. I mean, the Rolling Stones have quite a trail of dead bodies in their wake. I’m not laying the blame for anything at anyone’s feet. I mean, everyone’s a victim of this shit, even the ones who are doing it, and yeah, ‘sympathy for the devil,’ but no actually, he’s a cunt—and Jerry Hall married Rupert Murdoch. What more do you need to know? No one can help who or what they’re born to, but they can help what they do with it. Which is always jack shit—I mean bless them, but no, I don’t need Rupert Murdoch’s stepson telling me to ‘save the oceans’. It’s like, ‘Fuck you, fuck off.’ This is why I don’t get invited to weddings, I just want to egg Rupert.**

Iphgenia Baal’s Merced Es Benz was published via London’s Book Works in March, 2017.