I remember lying in a hospital bed, head turned, gazing out of the window. There was sky, I did not call it that. By then, the thoughts had been completely silenced. A bird flew off in the distance. I did not call it a bird, nor did I need to recall its distinct bird-ness in my head, nor did I really go so far as to discern the fact that it existed at a distance, only that it had, rather flatly, entered my field of awareness, like a fallen leaf passing on a stream. It was neither here nor there. It simply was. I understood that and took it for granted, along with my own was-ness. I let it be. Permitting it, without desire to follow it or to understand anything more, I then allowed it to be completely erased from my consciousness once it disappeared from view. What is more, I should say, that the I that saw the thing in the sky also did not exist. The boundaries between myself and every other possible thing was gone. I became reminded that I was an I when I saw a reflection, or felt pain.

I’m no semiotician or neuroscientist. I’m just a person who suffered the symptomatic equivalent of a stroke and congestive heart failure because of an unidentifiable brain infection, then recovered in a very condensed period of time (two years). I lost language, it happened over the course of three months, and in stages. First I lost reading, then auditory comprehension, then short term memory, then generating words. Regaining linguistic functionality took three times as long and re-emerged in the exact opposite order than when I had lost it. But I kept memory of the entire experience.

What we don’t realize when we see things, is, I think, that we recall every other instance of having seen something like it. And all of those instances sort of coagulate into a wave that forms a chain reaction, all underneath our consciousness, and too fast for us to notice (I was able to notice because my own functionality was slowed before it halted). A thing leads to the word for the thing, then an image, or images of the thing and things. Images are associations themselves, which lead to other associations (iterative image-inings or experiences), leading to feelings — distress, awe or, less dramatically, interest (all probably some variation of desire or repulsion) — finally precipitating in what we experience as top-level thoughts. Thoughts like, ‘There’s a bird flying around out there.’ There is also a lot of noise in our heads at any given time. Below our surface thoughts are all of the other processes leading to those thoughts, as well as whatever new information is still being processed at the same time. Then there are those long-standing psychological hangnails, like anxiety, insecurity, fear. Somewhere in all of this is a place where we draw a distinction between an idea of what the self is, versus everything else.

So – try to imagine. Without words, I lost the ability to imagine the thing-ness of a word in my head, or what it represented. I wanted a spoon, but hadn’t the word for spoon. Closing my eyes, I attempted to imagine what I wanted. I had no image either. Over time, the loss of this associative or imaginative capacity, led to a loss of feelings about things. I did not want anything, nothing was good or bad. Without thoughts, I was also free of anxiety, sadness. I had no need to “express myself.” I felt calmly coextensive with my newly democratized surroundings.

That is not to say that there wasn’t meaning. This is harder to explain. I could still understand that there was something that I needed – a spoon for example – not know the word or image for it, but generally know where it was. This may have been motor memory associations, still intact. Many times, I felt the meaning moving through me – like a magnetic current flowing through my abdomen in the direction of what I needed. I would follow the current with my eyes, or point to ask for assistance. I still didn’t know what it was that I needed until it was right in front of me. When presented with something that was, I could confirm or deny needing it.

My mind was also silent, completely and totally silent. Any time new, worded information tried to come into my head, with a doctor visit or a television show, it was deeply frustrating and confusing. As words were being spoken to me, I felt as though a waterfall was pouring down on my head. I could easily sit in silence for hours, watching a TV show on mute — images coming, going. As I said, I wasn’t unhappy in this state. I wasn’t really an I. I just was, and the world flowed around me. There was crying when pain or hunger was felt, or the urge to urinate. But when the urge was gone, so was its memory. I was in a space of radical presentness.

Out of the hospital, slightly more functional but still care-reliant, I woke up one morning to music blaring. It was Tom Jones singing ‘What’s new Pussycat?’ [Whoaaa Whoa Whooaa-oh!] but the song seemed to be stuck on the refrain. I slowly sat up and put my legs on the side of the bed, covering my ears. The sound wouldn’t stop and it was so, so loud, blocking ears didn’t make a difference. Then – I realized. The song wasn’t coming from anywhere. It was in my head. My brain had started working again, and it had announced it with a 60s adult contemporary pop hit.

This was the beginning of the most unpleasant part of my illness: I started getting better. The language came back, yanking me from my calm, quiet place, my bacterially-induced silent retreat, and into the iterable world. The progress was slow, staccato, it would happen momentarily and in bursts, but then revert. My brain would get tired, and I would stop processing again. After a year, my short-term and long-term memory had improved. I could make statements and tell stories, I was able to listen to people when they spoke and respond accordingly. With this renewed awareness came fear, anxiety, agoraphobia, and all of those fun internal dialogues we have about life and existence. Like, ‘I could be dead,’ or ‘I am afraid of dying.’ After a year and a half, I started being able to read again, slowly. I would lose focus like someone just learning after one or two words, then after five, then after ten, and so on.

I’ll warily admit that I have some nostalgia for the most serious stage of my illness, the radical presentness that I spoke about earlier. It was beautiful. Many of us spend much of our daily lives aspiring to stay ‘current’ or ‘in the know,’ using apps to stay connected to others, or to re-present our self(ies), endlessly swiping, scrolling. And to me, now especially having come out on the other end of this illness, I wonder what it all amounts to.

At one point long after I’d staged my recovery, a friend of mine asked whether I was afraid that I had lost language forever when I was sick. I responded that both during and after the illness I feared that I had lost my self forever; it wasn’t clear that what I thought constituted my identity would ever re-member itself. I recall wondering, as wonderings started floating around my head again, ‘Could I still be funny?,’ ‘Was I smart?,’ ‘Would I still be able to draw, to make friends?’ My experience of language, generating and receiving it, was inextricably tethered to who I imagined myself to be – that when it disappeared, I did too. As I was staging my recovery, I became brutally detached from the clearly delineated face I saw in the mirror. That person looked cohesive, it had a beginning and an end; it looked young and healthy (many people said to me “you’re too [young/healthy/pretty] to be sick”). But it was a stranger. What is more, posting images online became an odd ritual for me — abstracted from its original intentions, more symbolic of my regaining my former life than participatory social behavior. Interacting online felt very strange, like I was play-acting, showing a person that was active, engaged. I became a voyeur to the idea of myself, as I was constructing it.

Now that I am well beyond this phase of recovery, and feel slightly more integrated, I can’t help but reflect upon our current moment, where, for instance, more people post to facebook than vote. As humans existing in society, we often become so absorbed with how we are represented, or how others see us. It seems to me that we are so embedded in this act of engineering our selves, in this cannibalistic validation-seeking, data-mining cycle, that we are now in some kind of baroque era of linguistic/pictorial identity composition. We operate under the illusion, both in our literal and virtual lives, that whomever we are is stable, to be pruned and lacquered, presented and performed. This is nothing new, and many people have said this sort of thing without having had a near-death experience. Still, I’m going to put it out there: I wonder what would happen if we divested ourselves of this noise, momentarily, and attempted to witness the world from a more egalitarian viewpoint, truly democratic, unbounded. In a world where the ‘I’-ness and the ‘You’-ness didn’t matter quite as much, what would empathy feel like, or would it be the basis of all interactions? Language creates lines between things. What would happen if those lines became porous, tenuous? Having had unfettered access to the side of my brain that exists outside of language I know that it still exists in me, and in anyone with a brain. I imagine if we tapped into that space more, we might be able to relate to each other differently, finding more spaces for commonality than difference.

I think about this when I am casting judgment on somebody, or getting absorbed too deeply in others’ lives. I try to go back to that place where I could notice things, allow them to be – neither in contradiction or in conversation with anything – just being. I know this place to be part of me, but accessing it has become more difficult. I remember it fondly. And I have gone in search of it.

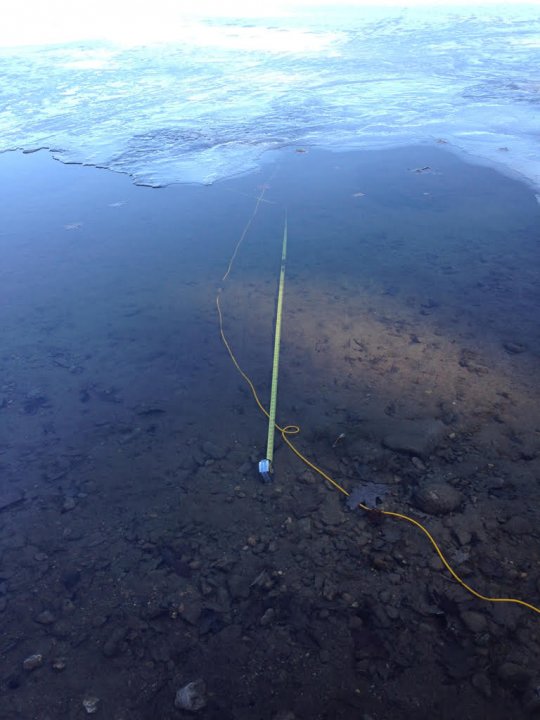

“What you’re talking about here is very zen,” a Buddhist friend once mentioned to me after I recounted some of what I’d experienced. (Many people have tried to project their beliefs onto this ordeal, and I’m still unsure quite what to make of it.) I allowed myself to be open to that label as a potential inlet to the part of my brain that I’d been missing. I joined a silent yoga retreat in the mountains to see if I could get closer to the place I once was, but voluntarily this time. Instead, I grew restless and anxious and went on walks in the snowy hills. On one of these strolls, I happened upon a lake. It was January, and the water was frozen, but snow made the temperature slightly warmer, and some of the ice had started to melt. There was a deep, glottal groan reverberating from the depths of the body of water, followed by laser-like superficial sonic pings that skidded towards you or away, echoing on the lake’s surface, which was stretched like the skin of a drum. This skin remained still, white, but the sound echoed in the basin of the surrounding mountains, and the impenetrably black depths of the water. I had been back in this place of words for about a year and a half, but still lacked a solid feeling of who I was or where to locate that “I.” But at that moment, I felt that I was seeing myself for the first time.**