Emily Berry writes she struggled with the responsibility as the annual editor of The Best British Poetry 2015, beginning her introduction with a tentative “Hi, it’s quite scary to be the sole editor of an anthology.” It’s an admission that feels distinctly gendered in its hurried disclosure. I felt it beginning this review, knowing no other way to acknowledge my own felt inadequacy as poetry critic than to deflect. The only honest critics, I am starting to believe, are the ones that know how to tell a story.

“On the one hand…who am I,” Berry writes, “to be deciding, on my own, what is ‘best’ (not to mention ‘British’)?” The question barely has time to register before she follows it with: “On the other hand I thought I was exactly the person to be deciding it. I mean, we all think that whatever we like is the best, right?” To be sure, what has made its way into the book is not the best of Britain in any way that is quantifiable or conclusive in its execution, but rather the best of Berry’s research, which proves to be quite enough.

In my mind –where what I like is the best –her results are extraordinary —a 70-plus collection of writings that manages to feel both timeless and patently of this time. It is no coincidence, perhaps, that the first five poems of the anthology are written by women, and that the gender breakdown of the anthology itself veers distinctly towards the feminine. That’s not to say that it is a “feminist” anthology, or one of “female writers” —it seems simply that given the opportunity to select content based on one’s intuition, as Berry did, one always chooses that which elicits a personal response. And what could be more personal, I suppose, than one’s gender and its tenuous existence in the strata of society.

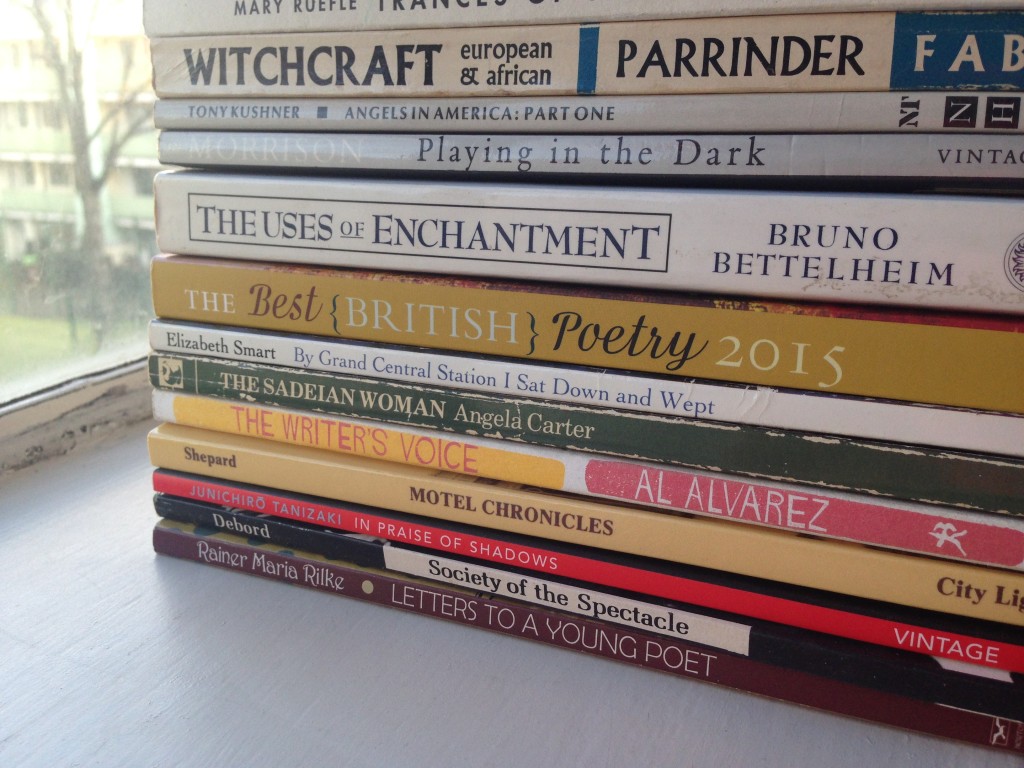

Aria Aber opens the anthology brilliantly with ‘First Generation Immigrant Child’, tossing her freedom and religion at each other like firecrackers—her “sucking and studying / another girl’s body, my mind a knot of tinkling beads / tangled inside a stranger’s unwashed hands,” then her headscarf in a mosque, her cousin whispering “Blood is thicker than water, / even for whores, her breath a verve of Darjeeling and Marlboro / Lights.” Astrid Alben’s ‘One of the Guys’ follows like the continuance of one long, interrupted thought (“not too much poetry / should be done by too many girls. You see, or elthe!”), taken up by Rachael Allen like a baton in a relay race with the poem ‘Prawns of Joe’ and this single, devastating opening sentence: “When I had a husband I found it hard to breathe.”

It’s not all women, certainly, nor is it all ‘women’s issues’ (though only the witless —of which there are so many!—would use that term). But the collection has a particular feeling, which, while basic enough once articulated, remains almost absurdly elusive: it seems to hold the experiences and idiosyncrasies of one sex in equal regard to the other, presenting each as nothing more or less than the experiences of a single person responding to the world around them.

One such experience, and my favourite piece in the anthology, is Paula Cunnigham’s ‘A History of Snow’, told in a broken dialect reminiscent of writers like Flannery O’Connor and the characters of antebellum. “It was a wild sudden,” it begins, following a young girl as she falls severely ill and is saved, in a moment of almost banal kindness, by a stranger at the hospital.

There are too many good pieces to enumerate –including pieces by Sophie Collins, Daisy LaFarge, Sarah Boulton, Jesse Darling –and besides: often it is the lines, not the works, that stay with you. There’s “…and I am running out of places to hide…” from Janette Ayachi’s ‘On Keeping a Wolf’; “another part which I can only describe as / the distance between distance / and distance” from Crispin Best’s ‘poem in which i mention at the last moment an orrery’. Then there’s basically every existing line from Kit Buchan’s ‘The Man Whom I Bitterly Hate’ and from Niall Campbell’s ‘Midnight’, which begins with the discovery that “all because I’d held my child, / oh heart, and found that age was in my cup now” and ends with this single indisputable truth: “no heart grown heavy, heavier, with caring”. **