“You haven’t actually ever seen any of my work”, says Cally Spooner, less as an accusation and more matter-of-fact over breakfast at a Middelburg hotel in the Netherlands. The artist would be correct. I’d made the three connecting trains and six-hour trip from London to the picturesque capital of the Zeeland region’s central peninsula only to miss the ‘On False Tears And Outsourcing – Singers deliver timesensitive instructions’ (2015) live presentation, having confused Vleeshal Markt in the city centre with the Vleeshal Zusterstraat gallery around the corner. I’d spent the eight o’clock August 1 event –which is, ironically, listed as “just-in-time, daily” in Spooner’s On False Tears and Outsourcing exhibition program –staring at a sign written with Dutch directions, while five minutes walk away the flash performance of singers was going on without me.

By all accounts, the four-minute event held in the cavernous late gothic city hall is a great success. I arrive in time to see the last of the audience loitering on the marble floor of the former meat hall with wine or water and the singers being congratulated for a job well done outside in the historic Middelburg town square. Spooner considers asking them to perform the piece again for my sake but as professionals it might be too much for their vocal cords. A passer-by on a bike says the sound had come like “a wave” and –perhaps delivered with a dose of that renowned Dutch directness –was “just bearable”. I can only imagine what went on. But the fact is I never saw ‘On False Tears And Outsourcing – Singers deliver timesensitive instructions’ and I have no idea what it sounds like.

“My shows can be very physical”, says Spooner about her body of work, which by now, being in her early 30s, is sizeable. “Maybe they’ve got screens, and lighting rigs, and speaking. But normally all of these components are hired, like the people. They’re these temporary assemblages of things that come and then go.” The ‘go’ part is key to what’s become my understanding of Spooner’s work, which extends well beyond business processes and affective labour, hysteria and the conflicted self of On False Tears And Outsourcing’s loose thematic thread and into the function of an artwork, and by extension its artist.

After all, my first encounter with Spooner’s practice was through what she had to say about it at a Lunch Bytes panel last year. As part of a selection of people put together under the Life: Language title at London’s ICA, Spooner spoke eloquently about the “big musical collapse” of her Tate Live commission ‘And You Were Wonderful, On Stage’ (2014) and an opera inspired by, among other things, Jean Cocteau, acrimonious online forum comments and the Lance Armstrong doping scandal.

Spooner’s ideas were intriguing and when the opportunity arose to see the real thing, I jumped at it. Except that what constitutes the ‘real’ in the case of Cally Spooner is complicated by the fact of her works’ impermanence. “I find this really difficult because in the absence of the work, which is regularly absent, I am all the time supporting it with this discourse, which is actually even not even a discourse that should be around those works. It’s just what I’m thinking about while I’m making it”, says the artist, who as a writer and voracious reader as well, tends to think (and talk) a lot.

Curated by newly appointed Vleeshal director Roos Gortzak, Spooner’s On False Tears and Outsourcing solo exhibition comes in several components. It’s treated more as a research project than a complete piece of work, and the program includes the aforementioned singing, a dance (with the overblown title ‘6 dancers, responsible for delivering self-organised efforts to resolve difficult and time-consuming issues, ‘go the distance’ across multiple overlapping phases, using appropriated competitive strategy and appropriated intimate gestures’) and an intensive Stanislavski’s method course including a notable Dutch instructor, volunteers and a financier. While I’m in Middelburg, there’s a pink sign on the door of the Vleeshal Markt that says “FINANCIERS ARE TRAINING TO PRODUCE TEARS; THE GALLERY IS THEREFORE CLOSED TO THE PUBLIC”. By now it would be gone but the exhibition still continues.

“Within the dance, within the sign, and within the song, there are choreographic movements within all of these things”, says Spooner about the three elements developed for her solo show at Vleeshal Markt. “There are vocals, there are textural gestures, there are graphical implications; there are things within all these that I do actually think stand on their own”, she adds about what she calls the “awkward politics” of her performances in their raw, unfiltered form. “It’s always this thing that I come up against because they might not contain any of the things that we’ve just been talking about. I’m talking to you about the mechanisms that enable me to make work or why I make work. But like, I think, all artists, the objects that come out –although mine are living objects formed from temporary assemblages of people, or temporary signage, or temporary lighting rigs, or whatever it might be –they could also carry other things.”

Anchored by the 1986 Bruce Nauman video ‘Violent Incident (Man-Woman Segment)’, Spooner’s Violent Incident exhibition, co-curated with Gortzak is the longest-running component of Spooner’s solo show and includes none of her own work. Instead, it draws from the collection on loan by De Vleeshal from Belgium’s M KHA and includes pieces by Nauman, Jef Geys, and Andrea Fraser; as well as other independently sourced works by Rosa Aiello, Danh Vo, Gil Leung and Bernadette Corporation. The three rooms of the second floor exhibition space are stark and white, but the sentiment is warm and vibrant. There’s a sense of humour here, a humanity that mirrors Spooner’s approach to taking potentially alienating business models and applying them to an art practice. It’s an exploratory procedure focussed on trying to understand the problematic nature of affective labour in the workplace by essentially replicating it, along with the paradox, whether by design or not. “I’m just interested in those spaces where you do manufacture emotions… industries that are designed to build certain machines or systems, or mechanics, or songs, or courses that produce affect in people. It’s just a big industry, isn’t it?”

As a result of Spooner’s fascination with this idea of “deploying affect” as a productive tool within the workplace –whether it’s in pop music, or a start-up, or method acting, or even Andrea Fraser’s embodied institutional critique in the ‘Official Welcome’ (2008) video featured in Violent Incident –she winds up perpetuating it. Gortzak emails me a fourteen-minute video documenting the earlier dances at the Vleeshal Markt, where six people embrace, push and pull against each other’s bodies in an act that is both intimate and supremely violent. Personal space is disregarded and tone confounds content as performers sneeringly shout out each other’s names, along with things like “Have a great weekend!” They’re in a slowly moving scrum of bodies that are repelled and propped up by each other; oppositional forces creating a precarious, and short-lived sort of balance. “You feel the struggle yourself, standing in the space, more so than when you’re watching it on the screen”, Roos tells me, next to Spooner at the Middelburg hotel, about these labouring bodies in a choreographed performance that appears spontaneous but is in fact highly structured.

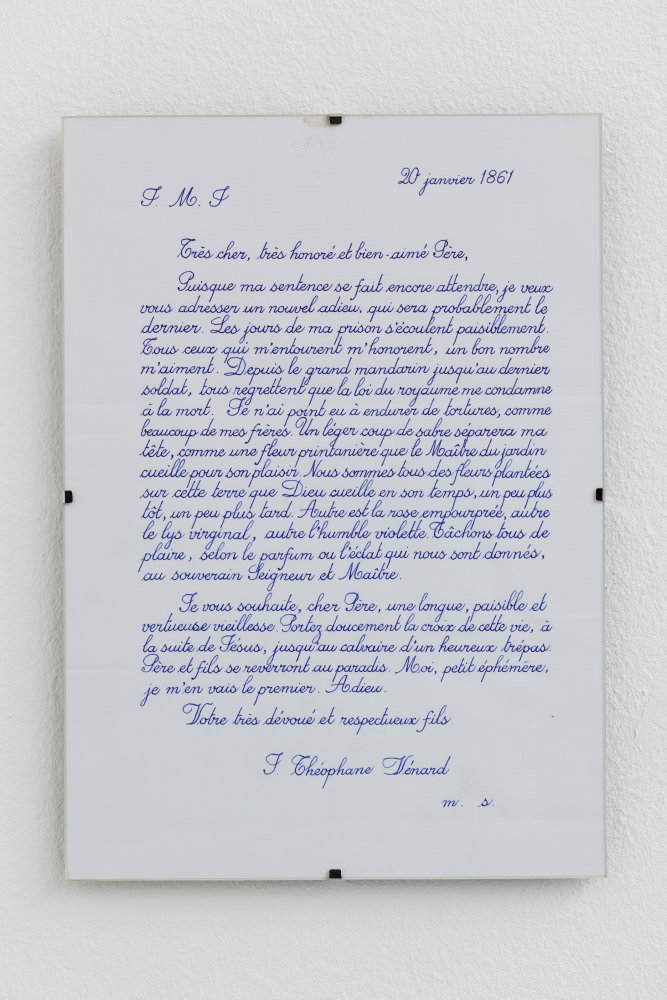

A “fucking cunt!” plays on loop from Nauman’s ‘Violent Incident’ (a video of two actors hired to mechanically hit each other over what looks like an intimate dinner) in one room of the Violent Incident exhibition. Gil Leung’s audio of an a capella of The Beach Boys’ ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ refrain competes in another. Fraser’s ‘Official Welcome’ is in the corner of one room. Rosa Aiello’s ‘Serving’ (2015) video –revealing the editorial tropes, devices and cuts, the invisible mechanics, of persuasion in cinema –is in a corner of the next one. Both videos have its viewer facing the wall, back towards the rest of the room and listening to the audio through headphones. The experience is intimate and it’s embodied. Jef Geys’ ‘ABC Ecole de Paris, 1959-1961’, ink crayon and coloured pencil on paper illustrations, hang across from Danh Vo’s as yet untitled Budweiser beer box with a pattern consisting of a repeated “Your mother sucks cocks in hell” printed in red Gothic font. His 19th century death letter, written in French and copied rote by the artist’s Vietnamese father is on the wall above it. In another room Bernadette Corporation’s ‘Oh snizzap!!!’ (2010) luxury bathroom fixture, inspired by a surprise series of naked Rihanna selfies and engraved with social media responses, is in the centre of the last room on a pedestal.

“I believe that an artwork should be able to carry all this stuff that we’re talking about without me having to say it,” says Spooner about the awkward position she inhabits as an artist essentially working in immateriality. “But the works do talk about that but you haven’t seen them because they’ve come and gone. I’m also not at a point where I feel like I can stabilise those works into discrete objects,” she adds while continuing on with a “breakthrough moment” that might minimise the problem of work that, in its absence, is always being explained:

“Six dancers arrive in the space, they run around, they clear the space, they start to call each other’s name, they gather together, they touch, they bind, they squat, they build the team, they do several handstands; they tackle each other to the ground, they embrace, they roll around, they fight the wall. I think I need to change my tactics.” **

Exhibition photos, top right.