Some people say collaging is lazy—a colour by numbers-style of art for those incapable of creating their own images. Some, who have spent no time consuming it, think only of grade school posters or the deliberate, sociopathic lettering of serial killers. Some people are dense, this we know. Because—and forgive the poetic sweep of this particular metaphor—what of life is not a collage? What that we do and say and think and draw is only a piecemeal reproduction of some other, more original thing—note that I said more; there is no point of origin for anything—that we’ve cut from our memories, consciously or subconsciously, and pasted to the present saying: I did this, this is me, this is my art.

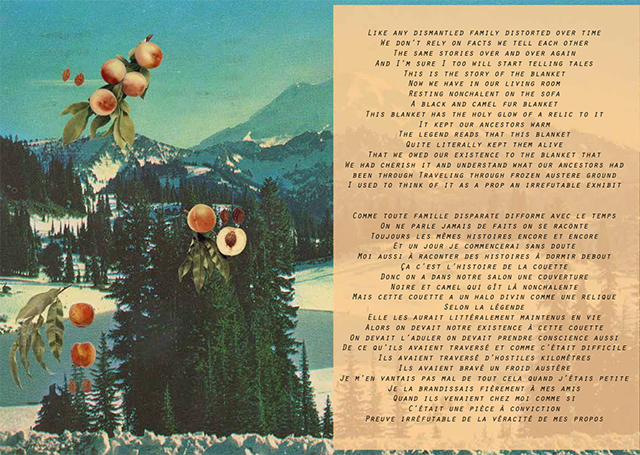

Orpheus Standing Alone’s new book, Menq Enq Mer Sarere, translating in English to We Are Our Mountains, looks at first like merely a book of collage, interspersed with compact poems that appear in both English and French throughout its 170+ harlequin pages. The book’s title, presented on the cover in its Armenian form, takes its name from a 1969 film by Soviet Armenian director Henrik Malian. The film—and the book, as we begin to see to deeper into it we go—encapsulates the sacred place that mount Ararat holds for Armenians and for the Armenian diaspora.

The two artists behind Orpheus Standing Alone—sisters Camille L. and Anna L.—follow up their initial self-titled publication with Menq Enq Mer Sarere as their second issue. The self-published collection chants an “ode to memory”, its multi-textured pages ringing out with photographs, poems, and collages produced in commemoration of the Armenian Genocide (1915-2015), crafting a “new way to think our memory”. It is, they write, “a memory for which no recollection is necessary”.

Memories for them, as for most survivors, are not merely historical: they are visual, lyrical, corporal. They cannot be written out chronologically or captured logistically; they are without time, without place. What do the two overlapping gold bands against the backdrop of the Ararat mountains mean for its creator? What does the tuft on green hair neatly clumped in a folded white paper mean for its? Who do these memories belong to, who were they taken from, and who are they being returned to?

The opening page in Menq Enq Mer Sarere begins with the word ‘memory’. Below are six definitions of the word and above, sepia-coloured photographs of women, their faces intersected and obscured by the rolling hills of the Ararat. The following page shows a woman in a patterned dress with yellowed arms, her face a sprouting flower. Beside the image, the text states: “The term memory does not or should not automatically mother memorial.” A few lines later, it reads: “This here is about how we embody our memory, about how our memory educates us. We lean on our memory, that of things that last. We are our memory.” And later still, we read: “A memory that operates discretely without our noticing, a memory of our senses constantly whispering to us. Sisters, we wish to embrace this memory, and have slipped it carefully into this box. Our history maybe a bit of a blur, and our memories sketchy and disjointed. Our memory, though, it inhabits us. We are our mountains.”