Morag Keil’s video of a foot, in a gold stiletto, and calf tattooed with a shaky-hands copy of Amy Winehouse’s pin-up girl tattoo towers over the ground floor gallery at London’s ICA for the Looks group exhibition, running April 22 to June 21. Faded a little by the daylight, like a hang-over in the morning, the leg is a show of the anti-puritanical body attitude that the late-UK performer lived by. In the original, the elaborately rendered word ‘Girl’ belonged to Winehouse’s nearby ‘Daddy’s Girl’ tattoo, but on this tribute leg it’s any kind of girl: girl!, girly-girl, daddy’s girl, my girl. Keil captures the complex subjective processing of image circulation as it occurs for each individual within the politics of self-representation; the sexualisation of women, the celebration of skill and/or sex appeal on stage, the aestheticisation of feet and skin, the agency of reclaiming it all by self-branding – by both outfit and needle.

Like a personal head-torch illuminating the remnants of someone’s dinner, or party, or life, this work reflects on Keil’s nearby video, ‘Untitled’ (2015), which is a stream of images from an Instagram account. Almost like advertising regurgitated, the work sees the world through the eye of an other after their obligatory and varied decisions and interpretations have been made;. where to go, what to look at, what to notice and record and how. In this context, it might mean which filter to use. The nearby towering leg doesn’t let us forget that the interpretative lens and the decisions of self-representation (through consumption and production, coagulating neatly in an Instagram account) are complicated and layered by structural and historical violence against personhood, which is processed in equally complicated terms by each of us.

Stewart Uoo’s floor rug coats the ground floor gallery, bridging Keil’s videos and the artist’s own dismembered mannequin sculptures, in a huge pink crust of cringe. Testimonies about the often stagnating pool of teenage hormones, social inexperience and libidinal misadventures from Cosmopolitan magazine lie underfoot like a foundation for our collective sexual (mis)maturing. Relations between men and women are rendered in terrifyingly reductive and stereotyped terms. Nearby Uoo’s photographs, collaborations with Heji Shin and picturing New York scene icon DeSe Escobar, render more complicated ideas of identity and desire. The images have the staging, glamour and vague sense of dramatic narrative that you would find in a Purple magazine editorial shoot. But they’re not a performance for the camera, rather the performance is the creating and exploring of identity. This is artifice that is deeply invested in play and provocation, when identity is a contested ground. As a counterpoint, Uoo’s two women mannequins, burnt and tortured into spectres of fashion, display their vacuity with very much inhuman glee.

Juliette Bonnevïot’s series of chemically complex monochromes are surprisingly alluring, with their cum-spurt surfaces and palette of xenoestrogens. The artist seems more enthusiastic about the manipulation and ethics of materials and compounds throughout the ages – to the current day – than the expression of identity, which makes her inclusion in Looks an unexpected one. In saying that, however, the key ingredient – oestrogen – of Bonnevïot’s series, which hangs in the ICA’s upstairs gallery, makes for a dexterous tracing of the contemporary treatment of gender dysphoria. What’s most interesting in the context of Looks, perhaps, is how Bonnevïot draws attention to the chemical and medical control of identity expression.

State regulation of bodies brings to mind Chelsea Manning’s recent judicial win in a US court to access oestrogen hormone therapy in military prison. In Manning’s case these manhandled–threads intersect with state surveillance and the right to information. Wu Tsang’s work, ‘A day in the life of bliss’ (2014), featuring performer boychild as protagonist ‘Blis’, moves lithely through this terrain, where subjectivity is on the run from the law. A sci-fi plot loses its slipperiness in moments of narrative blundering but the work, like Tsang’s practice, is uniquely invested in its subject matter and politically potent. It’s a high production two-channel video installed on two angled screens facing duo panes of mirrored glass, which reflect the projections in the round. The dualities continue in the parallels between the sci-fi narrative of neo-Orwellian networked observation and the reality of current revelations about the extent of government surveillance; the parallels and overlaps of the nature of identity and identification; and the living of life in multiple modes.

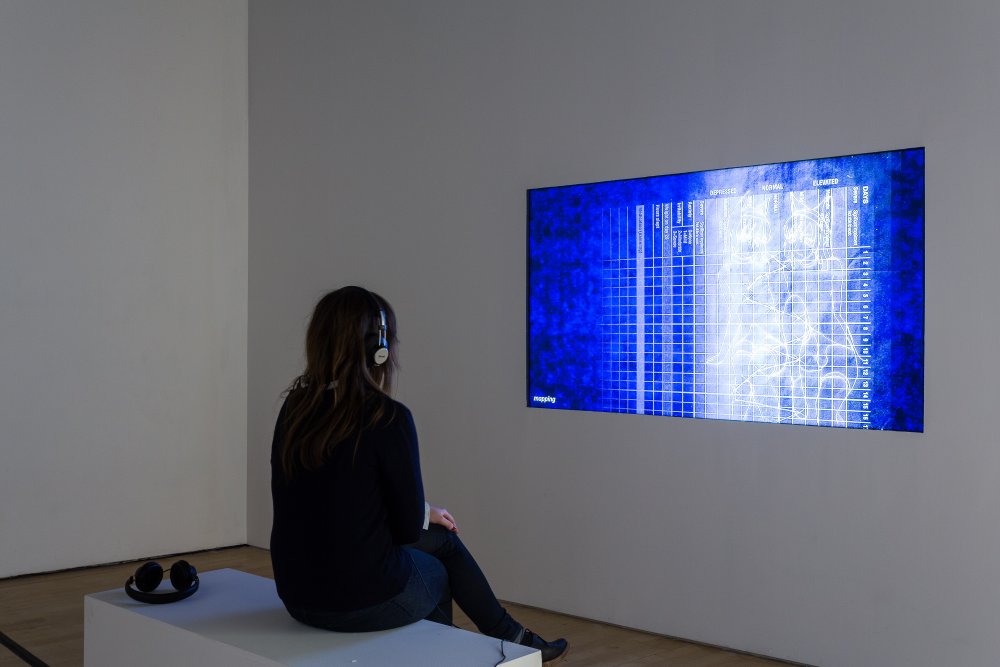

In Andrea Crespo’s video work ‘Parabiosis – Neurolibidinal Induction Complex’ (2015), a plurality of selves, commonly known as dissociative identity disorder, finds a community online where alternative subjectivities and bodies coalesce in a space of digital possibility. Online these subjects, that are otherwise unrealisable or dismissed, express corporeal experience and connect by compiling and sharing testimonies and images. Drifting over a darkened satin sheet the work levitates us into a sensual and yet non-physical space where drawings of ‘Sis’, a symbiotic sister-self, give form to bodies and libidinal desires that are until that point unrealised. Sex and desire online is particularly auto-erotic and Crespo shows the blurry intimacy between self and other, and self and self.

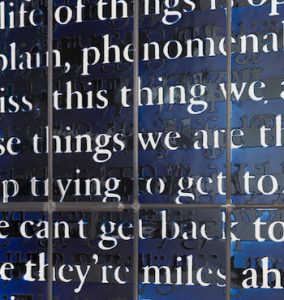

Terms expressing the variability of human subjectivities stream past on Crespo’s hypnosis-blue screen, alongside the language of psychiatry that categorises experience through mental health prognoses. Crespo’s language modes are poetic, diagnostic and self-identifying in turn, the last as a stream of hashtags: #actuallyautistic #polygender #stimming #borderline #bipolar; a cross-hatching of dialects to expand and reduce the subject.

The subject of Looks – the post-human world in relation to gender and sexuality – is broad, and to cover it with the work of five artists is a compromise. From the medicalisation of gender to the chemical splicing of matter, the social media hall-of-mirrors to the control of subjectivities, the net was cast perhaps too wide, which risks painting complexity as style. These artists are directly, inherently and consciously working in and with a context of marketing and dissemination but to mistake their treatment of gender, sexuality and identity as a trend itself would be to throw politically urgent issues out with this season’s look-book. **

Exhibition photos, top right.