For Hito Steyerl’s ‘Liquidity Inc.’ (2014), the ‘Inc.’ is essential. An incorporation, a corporatisation, it as much refers to the stable value of an economic asset as it does the “gorgeous, displaced animated water” of an online CGI lesson, playing out while Steyerl and associate Brian Kuan Wood joke about selling weapons for funding on screen. They communicate via countless chat and email windows that eventually inundate the frame, in the same way that water, or a simulation of it, engulfs the whole 30-minute film.

Water incorporates everything, and everything is incorporated. Reference to liquid is expectedly pervasive, whether it’s through a projection during central character Jacob Wood’s Martial Arts tournaments or on a plasma screen behind his back when sat in an office, at a desk, dressed in a business suit and writing on a notepad, “BE WATER”. It features in the mantra recited by Bruce Lee through an iPhone –his image reduced to its dimensions, voice distorted and autotuned as he repeats, “Be water my friend” –and it features on the main screen of the ICA theatre. That’s the biggest and most central of the five films scattered across rooms, this one is full to the brim and emerging to the right on walking into the pitch-black space of Steyerl’s self-titled survey of work between 2012 and 2014.

Liquid, along with the light it refracts, bubbles up, out and through a glass container, words and the very screen. It’s whipped up into a satellite view of a hurricane and washes through a jetty behind Wood as he recounts his early history as a refugee from the Vietnam War’s ‘Operation Babylift’ –a US imperative to evacuate and assimilate its enemy’s orphans into American life via adopted families.

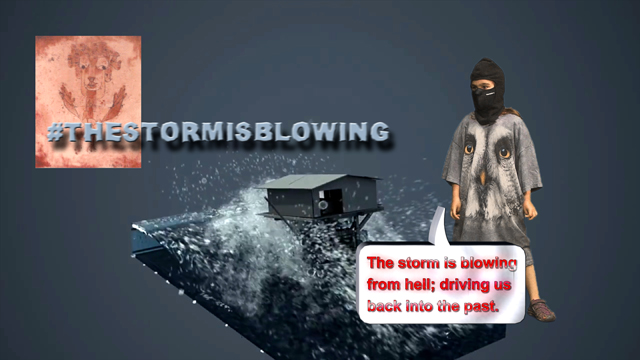

Wood would grow up to be a financial advisor, lose his job to financial collapse in 2008 and find a new calling in the Martial Arts. It might sound like a bizarre vocational digression but ‘Liquidity Inc.’ insists that it not only makes sense but it’s inevitable. In humanity’s networked and endless “fight to the bitter beginning” –as translated into English from the mouth of a little girl speaking German –a news report on Google Glass plays out as “a storm is blowing from hell; driving us back into the past”. The girl is wearing the same balaclava and t-shirt with an owl print, watching, as the adult representative of militant meteorologists Weather Underground does. He declares “your feelings are affecting the weather, and you are feeling not that great”. Those are the real-world effects of affective labour as illustrated via these weather forecasts and a tiled background of Ukiyo-e’s ‘The Great Wave’, mass-produced and flashing for popular consumption: “I am liquidity incorporated… the rainbow… torrent…cloud”.

There’s another browser window pop-up with its presenter announcing, “when you have liquidity, you’re in control” but one wonders if that’s true as animated 3D sketches of men in suits drown in the synthesised flood of a burst bubble with Wood describing a time when the money flowed freely during the 90s Dot-com boom. “It’s kind of like fighting,” he explains, while outlining the “shock proof portfolio” necessary to survive another economic disaster like the one that cost him his job.

The connection between business and war is made all the more insistently by ‘Guards’ (2012) to follow, while strongly implicating art in the process. Down a dark corridor and with its own narrow room, a vertical screen the size of its subject (or is it the authority?) presents Art Institute of Chicago security guard and ex-Marine Ron Hicks pointing his loaded fist directly at the viewer. But it’s less a standoff between Hicks and his audience than the invisible intermediary of the camera that faces him; its destructive, predatory nature felt all the more keenly as manager and “seasoned” police officer Martin Whitfield’s eyes falter under its gaze.

Hicks goes on to demonstrate his skills and training in ‘engaging’ his opponent, the gallery thief, while also explaining the “ancient art” of a particular defensive stance (“from there, we can do business”). Whitfield meanwhile explains that “art rather than people” has become the “priority response”; low-resolution images of social unrest playing out through frames of hung paintings, portraits of uniformed servicemen superimposed on the same walls that Hicks stalks in response to a hypothetical intruder: “Run my walls. There is no threat”.

Applause is audible from somewhere behind the ‘Guards’ screen, a sign saying “exhibition continues” points in that direction where the ‘I Dreamed a Dream’ (2013) and ‘Is the Museum a Battlefield’ (2013) lecture performances are playing on loop. Here Steyerl herself expounds on the unsettling collusion between art, business and war by making the logical connection between an artwork and German telecommunications company Siemens’ defence division, as an example. Audience laughter during the consciously farcical, though strangely lucid association between the 7.62 mm diameter of the hole in Barbara Hepworth’s ‘Single Form’ sculpture installation shot and the calibre of an ammunition cartridge, is punctured by the barking commands of Hicks in ‘Guards’ playing on the other side of the thin wall.

Steyerl connects her visit to a battlefield, running along the customised press release spam in her networked smartphone, to an exhibition funded by the very corporate body producing the ammunition her phone camera lens is apparently inadvertently pointing to at the moment she receives it. “Don’t’ ask who fired them but who sponsored them”, she says while Kris Martin’s 700 WWI Howitzer shells of ‘Obussen II’ become visible in the gallery, only when they become an artwork. The hole in Hepworth’s sculpture on the other hand is only “a shadow of a bullet’s existence”, where the effect remains but the cause is more elusive.

Decoding these symbols and abstractions of networked connectivity, making associations and implicating her audience in a funny, vigorous and intensely unsettling way is Steyerl’s ultimate strength. Her words from ‘Is the Museum a Battlefield’ –“it could be a data cloud or even a gentrified suburb” –echo through ‘How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File’ (2013), within its own four walls, separated and set between ‘Guards’ and ‘Liquidity Inc.’ An eerie automated voice narrates the mock instructions on visibility in a digital world, as a pixel-based resolution chart zooms out from the scale of Steyerl’s bust to the camera resolution test charts of aerial photography, then satellite imagery, on a planet where becoming “smaller than the pixel” is the only way to evade the gaze.

“Shoot or be shot” Steyerl tells us, while illustrating the ubiquity of the camera lens in her lecture. In ‘How Not to Be Seen’ “camera crews disappear when invisible energy rays emanate from the iPhone”, while the omnipresent automated voice explains “how to become invisible by disappearing”. The frame surveys a CGI plaza, its human-shaped inhabitants reduced to white silhouettes of negative space, while announcing “Love is invisible. War is invisible. Capital is invisible.” According to Steyerl, “resolution determines visibility” and there are ways of disappearing, into gated communities, military zones or by being female and over fifty. Better yet, become an enemy of the state, when you’ll be “eliminated, liquidated”. **