“I’m interested in how I feel about everything I come in contact with,” says “New Materialist” Nate Boyce, over Skype, about his practice spanning video, sculpture and ‘other’. Born in Kansas and living in San Francisco for the last ten years, he’s worked with the likes of Takeshi Murata and Robert Beatty, while dealing in some pretty big ideas. Talking to him about the complexity of the world at a macro level, beyond human subjectivity, can be as overwhelming as trying to deconstruct the references informing friend and collaborator Daniel Lopatin (aka Oneohtrix Point Never)’s R Plus Seven album, released on Warp, September 30.

The product of endless conversations and infinite variables across social constructivism, surrealism, procedural poetry and the philosophy of Manuel DeLanda, Boyce’s video for Lopatin’s Still Life expresses ideas from the reciprocal working relationship with Lopatin, despite the latter living across the country in New York and working primarily in music. Yet, somehow, Boyce’s sculptures are so abstracted, Lopatin’s music made so tangible that they bridge the gap from material into the immaterial, while exploring the blurred distinction between the physical and the virtual, the natural and the supernatural, in their respective explorations of transmuting (un)forms.

Their creative symbiosis is most apparent in their live performances, where Boyce’s image projections of figures, morphing and mutating, emerging and evaporating, interact with the Lopatin’s lurid, hyperreal soundscapes. Going beyond the earlier “slabs” of sound in, say, Rifts and Replica, R Plus Seven consists complex structural compositions, or what Boyce calls an “unhinged morphogenesis”, that functions on textural contrasts, exploring subjectivity and materiality. While watching these vital, formless forms one can’t help but try to ascribe meaning to them: am I looking at a cell? Is that anomalous ‘thing’ floating, or is it stationary? Is it pulling or parasitising another moving figure? Organic but otherworldly, it climbs the illusion of an incline, a liquid machine-like (non) structure that no words can make into matter.

At one point, during the unsettlingly cheerful melody of Problem Areas, the projection becomes a series of square boxes containing images of obscure sculptures by Joseph Slusky, suspended in a mirage of swirling clouds, resembling a screen, plucked from a portrait photographer’s studio and given life. As Boyce later explains to me via email, “it’s a mode of working that fell off since the art world took a very socio political turn for the last 30 years or so”. That goes some way in illustrating Boyce’s artistic preoccupations, which are anything but sociopolitically driven. Instead, his interests lie squarely in the aesthetic, “anti-anthropocentric” realm, one of objects abstracted: “even though it’s digital material, it’s still something I want to manually move.”

There’s are sense of your work existing in this realm of real unreality.

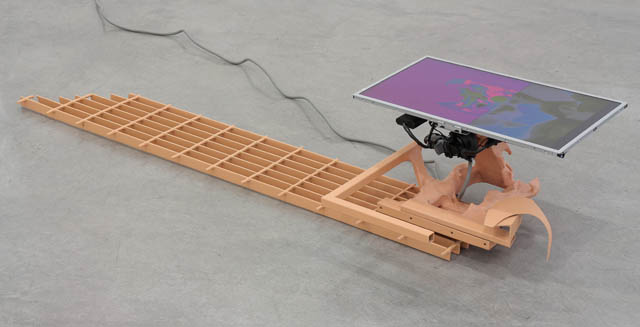

Nate Boyce: This is like the video for Still Life, of morphing out of this grid. The steel grating is thematic for the pixel grid or something but it’s also this organism, kind of morphing out. A lot of the things I do with Dan is purely in this virtual world, this kind of synthetic CGI space. Often times its like exploring a sculptural idea that I’ll eventually get to in real life.

Do you make a distinction between the real and the virtual?

NB: It’s funny because I’m sensitive to the areas of plasticity that make themselves available to me with different materials. With CGI, I’m interested in simulations. You can simulate physics, which I think is being able to become formally involved and formally experiment with gravity, and forces, and liquid simulations, all that. That’s not a set of parameters that is readily available in actual physical space. So I’m interested in all of that when I’m working on a computer; in accessing that set of parameters.

But then, working in the physical space, the computer still has a lot of rules of what you can do and how to make shapes that become apparent once you start working with it. Like, with this video here [Lavender] is actually a carved piece of foam. That’s like a real object that I shot on a green screen. Working with my hands, it has gestural residue.

So you couldn’t have done that digitally?

NB: I could, like I could scan it in or something, but in the computer, there’s something about the residue of gesture that is going to be created differently. This is like holding a tool with a bit of foam. I’m interested in that and then bringing that into the computer.

That makes me think about Dan’s use of OULIPO and procedural poetry, creating these self-imposed constraints.

NB: Yeah, constraints relate to selection pressures too, like in evolution. I’m interested in observing how, if you work within these constrains forms can emerge. In a sense, making sculpture is like a microcosm, or a simulation, of evolution in general; where within human subjectivity you create these constraints for the evolution of these objects.

You could even apply that to music. Like, after No wave destroyed any set rules on what constitutes music, you have to place limits on yourself within this new landscape.

NB: Yeah, this Cagean expanse of where all sound is all music.

And that could also apply to both Dan’s narratives and your sculpture?

NB: Yeah, totally. It’s funny because I use all my tools very intuitively. Theoretically, you can make any form in the computer and it’s going to be easy to do but at this point, I like to toggle back and forth in terms of accessing sets of formal parameters that make themselves available to me.

It sounds like your respective ideas really feed into each other’s work.

NB: I think this idea of R Plus Seven, which kind of implies this whole system of contingent structural possibilities, was a way to enter into a more sculptural approach to the music. You can see that with how the forms are much more complex, the pieces have so much more textural contrast and they go to different places and kind of morph.

I think that our discussions about sculpture kind of factored into that. Obviously my work is essentially, sculpture; it’s video but I’m interested in form. It’s like a kind of hyperformalism, a ‘morphogenetic formalism’, as I like to think about it. Maybe it’s like a bridge between my sculpture and this formal, procedural text-generation.

When I watched Still Life it felt like it echoed a lot of DeLanda’s ideas from that ‘DeLanda Destratified’ piece by Erik Davis that you and Dan both reference, particularly these motifs of liquid systems and synthetic organisms.

NB: Yeah, there’s this recurrent idea of morphogenesis; this sort of infinite mutability that anything can potentially become anything else. That it’s all matter and energy flows is another thing that’s important. A lot of my work seems like it’s getting into this. I’m interested in the idea of the natural versus supernatural. In the Still Life video there’s all these things that look like apparitions and there’s a certain cosmic horror. It’s Lovecraftian, in a sense, but it’s a very natural horror.

Do these ideas ever make you anxious?

NB: There are different ways of thinking about it. I’m more fascinated by the possibilities. I have a number of different emotions. I have a fetishistic relationship to materials and I’m interested in witnessing the potential for morphosis. I’m interested in this infinite potential for form and the complexity of how the human mind confronts those forms. Super-complex forms can be loaded with different emotional information and that can become very intense.

It’s not necessarily just about anxiety. It’s about a wide range of affective responses to the complexity of form. Sometimes it’s a sexual kind of feeling, like a sensual arousal, a fetishistic thing, and sometimes it can get into anxiety or fear. I think that range of emotions is on R Plus Seven too, at least with what I’m trying to get across with my work. I’m interested in the complexity of human affect in relation to the material world around us. I’m interested in how I feel about everything I come in contact with; different finishes on different types of material and the experiences or memories I bring to those interactions too.

Do you ever interact with these materials symbolically, say, if you saw the McDonald’s arches?

NB: If I was looking at the McDonald’s arches, I would just be thinking about the vacuum formed plastic that those are made out of [laughs]. I’m not interested in socio political commentary so much.

How come?

NB: You could say there’s something political about a certain philosophical vantage point and, in my case, it’s an anti-anthropocentric one; against this idea that these materials are subservient to human interests. I’m interested in different theory, I’m into DeLanda, I’m into Bruno Latour, phenomenology. Ultimately, I’m aligned with, maybe, some kind of New Materialist way of looking at things.

Do you think that if you were in different circumstances that your philosophy would be different, if you were being violently exploited by the machinations that these materials might represent, for example?

NB: Maybe my philosophy is developed within a purely aesthetic way of thinking about things. There is a kind of violence and aggression in my work though, a range of associations and feelings. Hopefully it’s extremely complex, that there isn’t just one kind of feeling that’s being conveyed.

There is an aspect of pathos. I like images and sounds to be aggressive because they make you aware of your body. But I can’t go so far as to say that I’m somehow a conduit for some sort of nefarious system of exploitation that ultimately underlies the technology that’s being used. I can’t really speculate on it so much but I guess someone could read it that way.

The ‘complexity’ you talk about. Watching your videos there’s a mood that I can’t put my finger on. There’s a sense of the awful sublime.

NB: For instance, at the beginning of that Still Life excerpt I did, there’s this quasi-arm plunging into this surface. Maybe that’s sort of a metaphor for how I want to deal with the video. I just want to reach into the screen and manipulate the material. **