To most people in the art world, the name Gerhard Richter is synonymous with blurry photo-realist paintings with echoes of post-war East Germany. Yet, as Panorama, the retrospective exhibition at the Tate Modern demonstrates there is a lot more to Richter than a bit of blur.

Unexpectedly, the gallery known for its resistance to the more traditional curating strategies adopted a chronological hang to structure the body of more than 50 years of painting, photography and sculpture. Starting with the photorealism of the 1960s, the exhibition slowly ushers the visitor into Richter’s thought process. He reveals himself to be a contrary character who has adopted this particular aesthetic that will become his signature as a means to distinguish himself from all the painters in thrall with abstract expressionism at the time.

This oppositional streak is confirmed by a whole gallery space filled with works responding to Duchamp’s sweeping statements about the limitations of art. Just then you might think you have him figured out: he responds to his time by providing alternatives to a dominant aesthetic. Yet, the damaged landscapes and the grey paintings, ranging from thick impasto abstractions to flat blocks of grey tones will confound you, especially since he follows them up with a return to his blurry aesthetic applied to both photo-realism and abstraction.

For most artists, this full circle would be the result of a whole career, but not for Richter who somehow decides to embrace his obvious fascination for abstract expressionism two full decades after it’s run out of favour amongst his contemporaries. What starts as large canvasses covered in angry stripes and splatters of lurid colours will evolve into the other body of work that Richter is famous for: the squeegee paintings. Layers upon layers of oil paint are pulled – and blurred – laterally and vertically with an actual squeegee, leaving behind the traces of partial erasure. These works are fascinating for their weight: in oil paint, in history and in contrast to the photo-realist works he keeps doing in parallel.

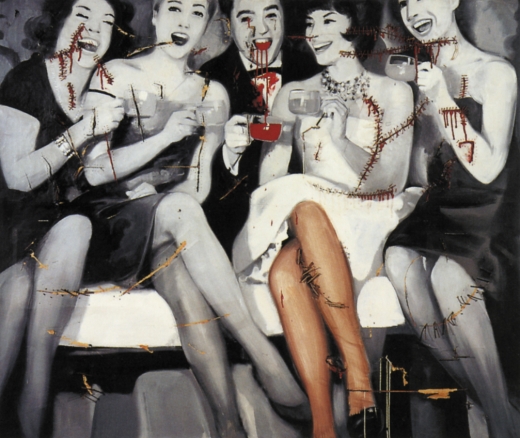

- Party – 1963 by Gerhard Richter

On top of these two intersecting bodies of work, the exhibition also comprises some of the photography that Richter used as source material and a few of his sculptural installations with glass. His painting is so strong and so obviously the result of impeccable technique and years of tweaking a process that his sculptural work appears thoroughly ineffectual and patchy in comparison. Somehow it’s a relief to see that, at the ripe old age of 79, there still things that he gets to experiment with and that he has not yet mastered.