The art world loves dead women. With innumerable recent efforts to expose artists until now neglected, an urgent question emerges about the mechanisms underway. In writing these recuperative histories, intricately involving an artist’s work with their biography, it is necessary to plot responsibility. And how might this extend for younger artists, perhaps those already being seen, who face the same world of reductions? Crossing time, Carol Rama and Darja Bajagić are two artists whose practices might map some of the uncontainable means for resisting such easy interpretation.

Carol Rama lived and worked from 1918 to 2015 in Turin, Italy. Only a few years past her death, Antibodies, the first major museum exhibition of her work in New York, and the largest ever in the US, opened this year at New Museum. In May, Space Even More Than Time opened at the Archivio Carol Rama at the Palazzo Ca’nova in Venice, the first here in a decade, during the Biennale (where in 2003 she was awarded the Golden Lion). In 2014 the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) opened The Passion According to Carol Rama, which toured Turin, Dublin, Finland, and Paris until this year. The show was curated by Teresa Grandas and Paul B. Preciado, who sought to rigorously ‘expose’ the work of Rama and map it as a critical ‘anti-archive’ of mutations and reformulations. The list of ‘firsts’ (and other excited claims) could be mapped across the years of Rama’s life, and might just tell of the power and brilliance of her work, of the induced desire to somehow both possess and celebrate it, particularly when encountering it for the first time. Knocked out, this was my sensation, too.

Italian critic and curator Lea Vergine is often credited with the first ‘first’: in 1980 (Rama was aged 62) Vergine included her earliest watercolors in The Other Half of the Avant Garde, an exhibition of over 100 women artists at Palazzo Reale, Milan. In this moment Vergine ‘discovered’ Rama, crucially bringing long-overdue attention to her work within the space of the museum, where she had remained largely unacknowledged till then. This is an interesting problem, because Rama had, in fact, exhibited consistently throughout her life until this point. Mostly, the artist had received gallery shows across Italy with the committed and repeated support of significant gallerists and critics, as well as fellow artists and poets, since her very first show at the Faber Gallery, Turin, in 1945 was swiftly censored and the works seized (stolen, lost) for obscenity under Mussolini’s government before it opened.

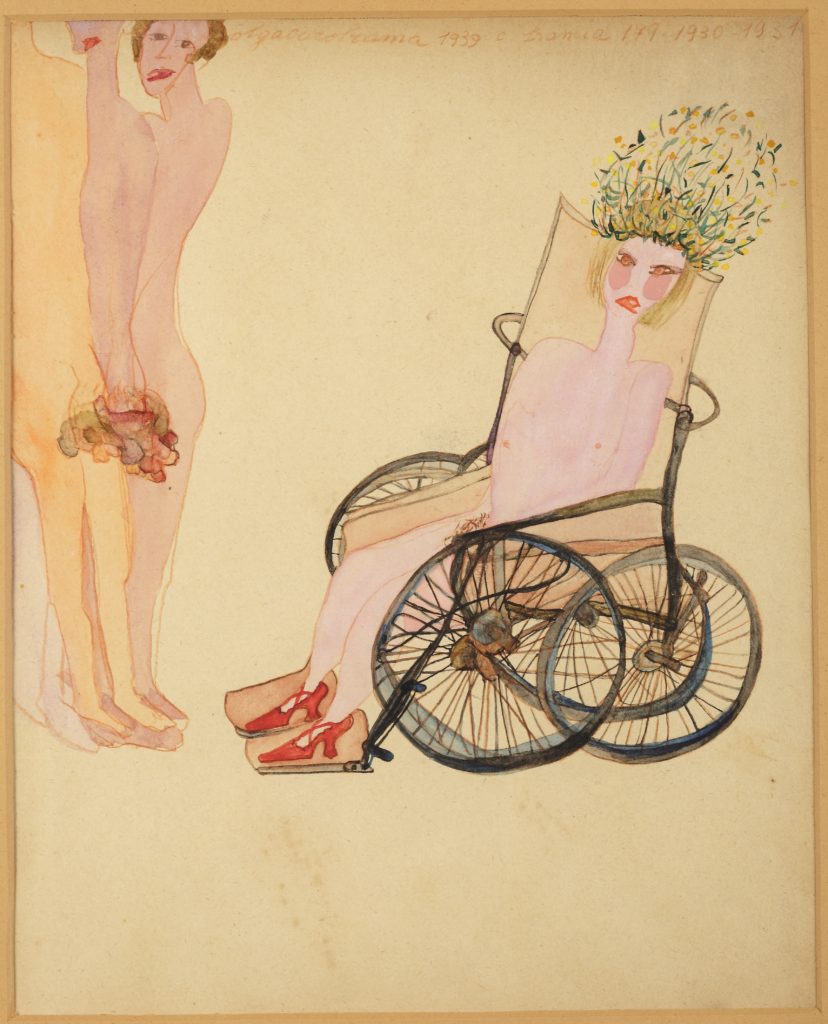

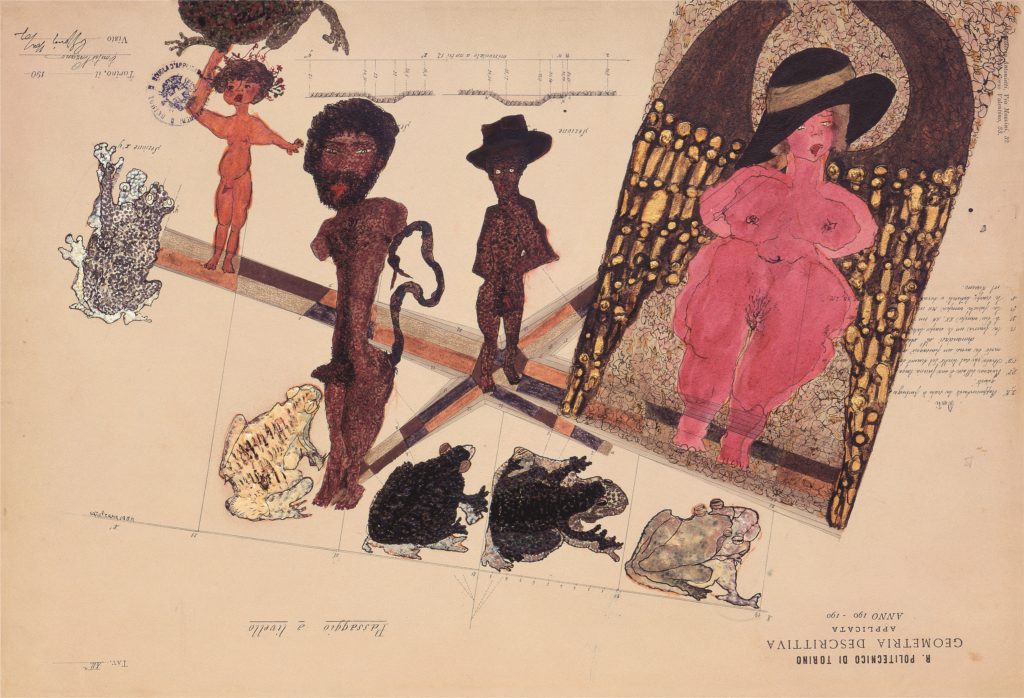

Self-taught, it was Rama’s Appassionate works, begun in the 1930s, that were to be presented in this earliest unseen exhibition, and then again, as if for the first time, in Vergine’s major show decades later. In these pieces Rama renders dismembered figures crowned in flowering gold, strapped to beds and wheelchairs, tongues wagging, naked and blessed with multiplying dicks and cunts, twisting feet, floating teeth, sometimes shitting, also fucking. Beasts and snakes often also take part in this frenetic situation. Rama spoke in interviews of spending time with her mother in a psychiatric clinic around the age of 12, learning a freedom in the gestures surrounding her: “I saw these women, squatting on the ground, with their legs spread, their asses in the air, and I believed the entire world looked like this, no?”

This censorship and labeling of Rama’s art as ‘pornographic,’ and later Vergine’s ‘discovery,’ describe two of three “critical operations” — invisibilize, discover, reduce — that Preciado (in an essay titled ‘The Phantom Limb: Carol Rama and the History of Art’ for the MACBA exhibition catalog) declares ensure the construction and continuation of a dominant art history, a time and place that would rather omit Carol Rama, or at least until it might recuperate her far too late. Living in this delay, Rama recalled to Vergine her memory of attending the show, “I go to the opening… and I see myself presented there in such an extraordinary way, I was afraid I’d be physically ill. It pissed me off, sure, because if I really am so good, then I don’t get why I had to starve for so long, even if I am a woman.”

Rama’s words and Preciado’s theory echo for the many recent recuperative arrivals of artists like her (“somatopolitical minorities,” in Preciado’s phrasing) very late into their lives, even only posthumously. These efforts at present appear across the entire field — in alternative spaces, galleries, museums, at auction, and in the publication efforts of these spaces and others — soon embraced within the market, treasure troves of an entire life’s powerful work. In Preciado’s argument, even Vergine’s exhibition inevitably maintains Rama outside of time, denying her contemporaneity by representing only her earliest works many years later. The decades in between and the work she was actively making at the time remained thus invisible at this exhibition, which is so often notated as Rama’s first major public exposure. At the same time, Vergine’s presentation prompted her active return to the figures of the Appassionate, now vividly grafted onto the pre-existing grounds of technical maps (of cities, of the world, many titled Seductions). These later works, made from the 80s onwards, are populated once again with freakish figures amid textured animals, twisting appendages, powerful waters, casting spells. Both troubling and emphasizing Preciado’s argument, this speaks to the powerful ranges and returns in Rama’s work.

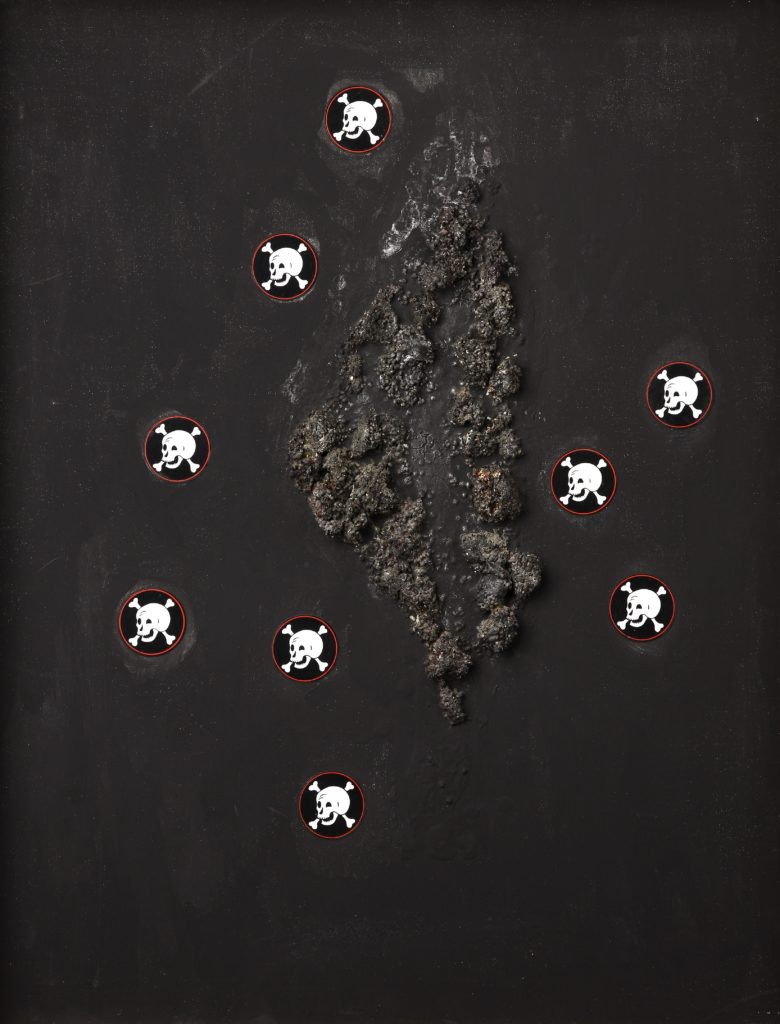

Facing the blow of censorship and by “her own radical determination,” (as Vergine reports in her now oft-referenced and republished 1985 text, ‘Carol Rama: Heroic, Exotic, Heretic’) by the 1950s Rama had turned to the order and limits of vastly more abstracted compositions. This transition is such a visible one, into larger paintings containing flattened constellated forms in glistening and textured paint, “but for those who are capable of seeing it, the subject is always the same.” Into the 60s Rama developed her Bricolages (so named by her friend, the poet Edoardo Sanguineti, who presented and wrote on her work in Italy until late into his own life), where these abstract compositions began devouring other materials. Taxidermy eyes, syringes, teeth, tangled wire, false eyelashes, animal hides, and other things amorously grasped by Rama from her world tell of immediate bodily sensation, as exploded innards would. Nearing 1970, she introduced rubber tire inner tubes cut open and splayed, pulled, or draped limp. Rubber recurs incessantly until her death, and is key to considering Rama’s understanding of materials as they cross with her biography (the story goes that her father committed suicide after the family’s tire factory went bankrupt, although there are alternative tales): “Tires remind me of my father, the factory, they remind me of power. But then this is not completely true, because they were unimportant bicycle tires.”

Rama resists reduction. Although by the moment of her public discovery this might already be underway. This is the third operation, per Preciado: “The artist is reduced to their biography, ethnicity, body, sexuality, class or social condition, functional differences, mental health… as if these were universal and stable parameters and not the effect of existing relations establishing the field of visibility and power.” I’d like to press at Preciado’s call — that “it is necessary to defeminize, defolkoricize, defetishize, depathologize, and depornographize Carol Rama” — which, if already too late, seeks to assert how we might handle Rama and her work now, today, in its increasing public circulation and prominence. And how might this extend even further into the present? Preciado’s own inevitable involvement in these processes indicates the complexity in establishing such urgently delayed discursive mappings. Writing for this year’s Venice exhibition catalog, Lia Gangitano also suggests a means for mapping, finding artistic kinships “like pentagrams, crossing time,” that might leave behind the rigidities of chronology or a pathological reflex. This might also be understood as a mode for responsibility, seeking to care and then care further for how and where an artist is placed.

Darja Bajagić was born in Montenegro in 1990 and currently lives and works in New York. Her work most often features explicitly pornographic and graphically violent imagery combined with other contents, refusing any point of a moral stance. These materials include imagery from fetish porn publications and sites, ‘murderabilia’ relating to the violent deaths of women who appear named in her works, circulated images of missing girls (also named), tabloid news on such events, and other materials produced by the sheer enthralment that seems to tie these things together. While on the road her father, a long-haul trucker, collects the motorcycle patches that provide the text in many of her works (they are also found online). The 2014 work Come To The Dark Side We Have Cookies!!! takes its title from one of these patches placed at the corner of a large black expanse. This red-lined text flap turns open to follow, ‘Welcome to the Dark Side/Surprised we lied about the Cookies?’ In other more recent works, text might be placed directly atop a named face. This sense of humour remains.

All these materials and their channels indicate an obsessive and expanded form of consumption (research), standing as a multiplying and temporal volume that the viewer accesses through careful formal arrangements. Bajagić seeks to deterritorialize meaning, opening and entering the charged spaces of her materials while refusing to pornographize in a reading of these images. Rather, they are held open to ambiguity and ‘switching,’ acknowledging and muddling the drives behind this desire to collect and possess. By this, Bajagić’s work has faced processes of censorship and biographical reduction, but has also already been exhibited widely and received critical attention. While with visibility an artist, still young or past their life, might not face outright ‘invisibilization,’ they do by these operations face reduction, being misread, pathologized, poorly handled.

As contextualizing shorthand, writing on Bajagić often recounts the story of her experience as a student at Yale. A BlouinArtinfo feature quotes her on this: “I met with Robert Storr, the head of the department, and he literally told me I was crazy […] And that Yale would pay for all of my counselling and therapy during a leave of absence to seek help for my obsessive-compulsive behavioral habits of collecting images of girls and porn… that I should look deep inside of myself to figure out what are the problems I have with myself, as a woman, for being okay with these kinds of images even existing in the world, let alone propelling them in paintings and in the gallery system.” The article rounds out, “Bajagic countered that she was already achieving some degree of recognition for the work, outside of the academic program. ‘Of course,’ she remembered him saying, ‘Sex sells.’”

Knobloch, and Beate Zschaepe’ (2017). Courtesy the artist + Carlos / Ishikawa, London.

This reporting is embellished by the title, ‘Contrary to What You May Have Heard, Darja Bajagić Is Not Crazy,’ in the strange, if not reckless, but unsurprising form of clickbait copy. Already twisted, Storr’s words and BlouinArtinfo here corroborate this process in live-time, an inborn acceleration of Preciado’s invisibilize-discover-reduce problem, landing fast upon absolute pathological reduction. This reduction continues when the work fails to receive any responsible reading, already dismissed for its shock value. Or, of course, when it is mediated precisely for this effect.

During the 1940s, Rama’s work, still in its own early phases, was marked and removed for its pornography under Mussolini’s fascist rule, the context within which she would nevertheless continue making work. Yet, even the tastes of the Italian art world, its parameters inevitably also marked by this regime’s processes, had little means for placing the artist within its dominant movements.

Today, a whole other time and place in which Rama’s work also lives, Bajagić faces the possibility of censorship and controversy each time her work is shown, processes which seems at present likely only to expand in reach and control. A more injurious threat might just be in visibility, in the knowing hands of the critics, curators, gallerists, collectors, donors who take up the task of handling this work, forming this history. But Bajagić, across time with Rama, shares in knowing the power and the trouble of debasing interpretation. Admitting one’s own obsessed involvement, and still refusing the production of meaning.**