Dutch artist Jacqueline de Jong joined the Situationist International in 1960. Comprising a network of writers, artists and theorists, the collective synthesized traditional Marxist thought in various attempts to derail the expansion, and embrace of capitalism and Keynesian economic policies following World War II. The Situationists employed détournement (French-to-English translation: hijacking, misappropriation), a prominent technique used in anti-authoritarian disobedience in the mid-twentieth century where corporate logos and symbols were reworked as a means of capitalist parody and critique. Fifty years later, this tactic at its best might look like early 2010s obsession with 1990s posthumanist theory cloaked in sportswear and energy drink apparel. At its worst, Banksy’s trivial analysis of Disneyland in a ‘Dismaland’ theme park. This system has seemingly become really subsumed, reifying irony as sincerity, a self-effacing détournement of détournement.

Void of common brands and overly-legible contemporary referents, the works in Imaginary Disobedience at de Jong’s first solo show at Los Angeles’ Château Shatto, running from March 18 to May 6, understand the potential problems of weakened methodologies in world-making. Social and political action is often attenuated to performance and mere image-sharing on privately-owned public networks, allowing for flattened yet permissible standards of attention that ultimately mitigate paradigmatic change. This generates a phoney arsenal for disobedience, a profusion of weapons made with cheap metals that create a collective delirium after recoil. These tools and their affects leave us reincorporated into the institution and State, while feeling falsely accomplished in its disassemblage.

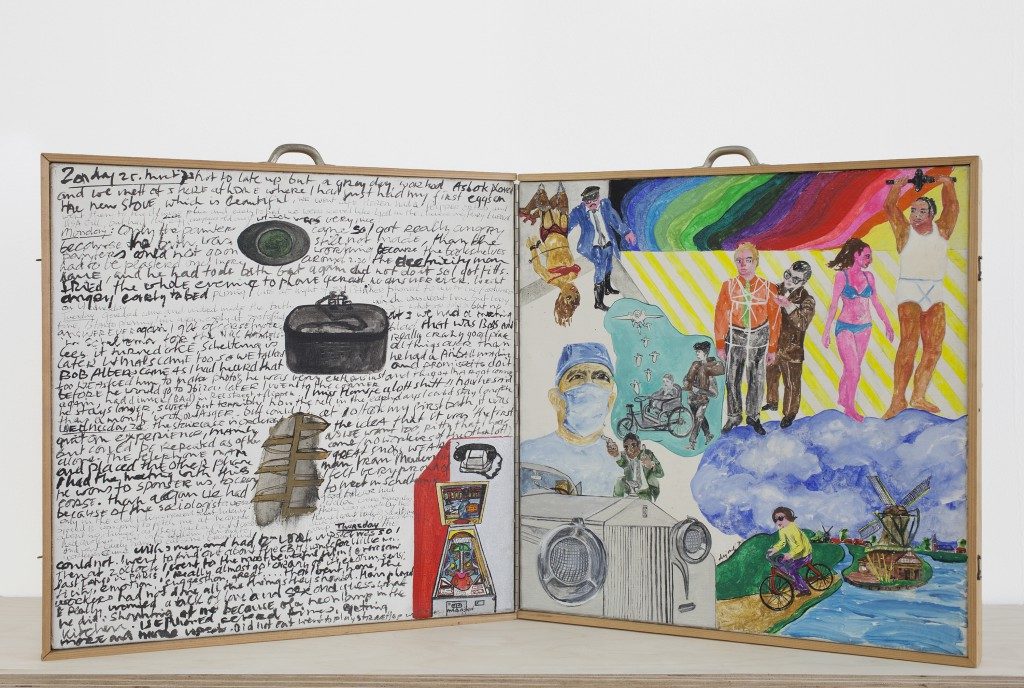

The left wall upon entering Château Shatto presents three acrylic paintings of the same format on separate shelves. Each one is composed of two wood panels (on the left are diaristic texts from de Jong, on the right are various illustrations of characters and events of the late 20th century) connected by a hinge in their center. Though impossible to make out a complete phrase, the painted internal dialogues are enticing enough to elicit curiosity by a rare, clearly-scripted word and the mention of names and places; the sentences are legible until they aren’t, history can maybe tell us how the complete texts might read. The right panel of ‘After four hours the beans are revealing themselves’ (1971) depicts (amongst scenes of nuclear weapons deployment, bondage and pastoral bike-riding) a doctor clad in a surgical mask, a possible reflection on the opening of the first legal abortion clinic in 1971 in the Netherlands, where de Jong was born.

The most engaging works in the exhibition express an analogous relation between animal subordination and the instruments of control (racialization, incarceration, revoking health insurance as eugenics) that Man indoctrinates to designate and reproduce others as non-human, prematurely dead, socially and materially regulated and disenfranchised. The foreground of ‘The Ultimate Kiss’ (2002-2012) shows a goat’s skull being licked clean after its fibrous muscle tissue and organs have been devoured. Its eyes are still intact so that it may bear witness to its own slaughter in sync with the tribe of goats in the background. Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe writes that “in the logic of survival one’s horror at the sight of death turns into satisfaction that it is someone else who is dead. It is the death of the other, his or her physical presence as a corpse, that makes the survivor feel unique.” The separated living tribe don’t quietly watch death as much as they bask in their own libidinal affectability. ‘The Ultimate Kiss’ names a depraved psychosexual act wherein unilateral exertion of power and atrocities committed by the State, the war machine, the colonist, transmute horror into an erotics of survival and aliveness.

de Jong’s impressive body of work beginning in the 1960s does not (and should not) produce a litany for threadbare methods of insurgence. These resistance attempts indulge a timeline of the end of the world that is maintained with wicked quantum calculus, using constant recursion to insist the apocalypse always begins in the now. In not shying away from the manifold and historicized ways that pain and violence (real, sublimated, abstracted, law-maintaining) animate, vitalize and hide themselves, de Jong presents an archive contra Western sensibilities that are delayed in enunciating long-known axioms of turmoil for the first time. Imaginary Disobedience as a whole functions as a cruel aphorism not dissimilar from Biblical parable, wherein Man’s dissimulation of his own hideous origin are revealed to himself.**