“I wanted to find a way to create a work which somehow discussed the relationship between art and money,” says artist Mike Nelson while installing his work at Turin’s Galleria Franco Noero, “but in such a way that it wasn’t too didactic or overtly critical.”

Active for more than 20 years, Nelson has twice been nominated for the Turner Prize and represented Britain at the 54th Venice Biennale. His work often features temporary large-scale architectural installations; immersive environments that subvert the viewer’s sense of place by transforming multi-layered discursive structures into mesmerising constructions. His art is very political, but it’s never strictly about politics, pointing instead toward fundamental human matters. Reality and fiction overlap, and by this, like a meta-narrative, he manages to reveal systems of thought that have been imposed upon us.

In Cloak of rags (Tale of a dismembered bank, rendered in blue), running at the Italian gallery from February 6 to May 15, the London-based artist uses the precious pigment Ultramarine Blue as the jumping-off point for a whole series of considerations. Namely, the complex relationship between art production and finance, in an attempt to map an ‘archeology’ of contemporary geopolitics between the West and the Middle-East and its dynamics through the narrative potential and economic connotations of this colour. Ground into a powder from a deep blue semi-precious stone, lapis lazuli, the colour has been highly-prized since antiquity. It was widely used in Renaissance painting, as well as in ancient Egypt and by the Sumerians. The gemstone has been extracted from the mountains of the North East of Afghanistan for millennia, while recently becoming the second largest form of funding for the Taliban, after opium.

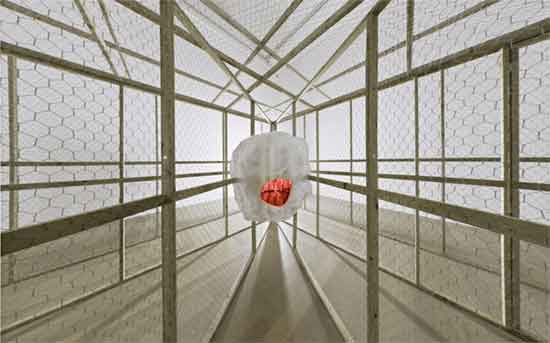

In his previous exhibition, Cloak — a site-specific intervention presented by Nouveau Musée National de Monaco (NMNM) in 2016 — Nelson had completely painted the inside of a large nine-storey headquarters of UBS Bank, in Ultramarine Blue. After the building was demolished, he collected the blue rubble, turning it into the sculptures we now see in Franco Noero.

For Cloak of Rags, Nelson carries out a particular currency exchange: a structure that for years has had the task of guarding money has been painted with a colour that for centuries has symbolized social status. That is, only to be dismantled and transported from Monaco to the gallery in Italy, with the aim to create a show of debris that, in the context of the art, can renew themselves and assume a new value in the form of sculpture.

** Can you tell me about the use of the colour blue for this show?

Mike Nelson: I thought this was an interesting way to think about the historical relationship between art and money, but also the complexity regarding how the world is structured economically in terms of global finance. As a colour, it is also related to political dynamics, in regard to its origin being from Afghanistan. Ultramarine literally means ‘from over the sea,’ and it’s a beautiful image, especially when you stand on the sixth floor terrace of the bank, overlooking the Mediterranean. Rendering something blue also has a phenomenological effect on the viewer: it’s a potentially trance-inducing experience. It aggravates one’s sense of reality, complicating the potentiality of the historical and political meanings imbued in it. It also reminds me of the image of the blue screen of a computer, an in-between image, a reference to another possible reality.

** Your piece has then been transported to Turin.

MN: Even before I realized the work, I was already thinking about the potentiality of the demolition of the building. The reason why I was invited to make a work was because the building was due to be part demolished, and all the interior rebuilt. The imagery of demolition was very clear from the beginning, it was an interesting part of the whole process. So, after the closure of the project we physically cut sections of the building out and brought them back to the gallery. It’s a shift of currency, because in a way we’ve taken the very structure that was once used to house wealth – almost like tomb-robbers of old – and brought them back to Turin. However, all you see from this building now has no inherent value; it held, demarcated and accommodated huge value, but now it’s just bricks, wood, pieces of furniture… Now we’re constructing a sculptural exhibition of objects that potentially have another value, as something deemed art. There’s a melancholic discourse on shifting economies here.

** The idea of rebuilding and creating a work of art from a previous destruction was also present in the piece you made in the basement of the gallery.

MN: I think it’s quite a recurring motif in my work. If we go back to my MA show in 1993 at Chelsea College of Art, a work called A staging of the reconstruction of the southern palace of Babylon, it was a reconstruction in concrete blocks of a section of the southern palace in Babylon. The work took as its starting point the somewhat insensitive – especially to western archaeologists – reconstruction of Babylon by Saddam Hussein, who was interested in the manipulation of culture for his own political ends. There seemed a dark humour in the horror of the archaeologists when one considers where the missing parts of Babylon are!

My work was constructed out of similar concrete blocks, to scale and on compass settings. Visually within the gallery space, it felt like a foundation course on which a new building would be built, but also like a set of mock ruins. In many ways it comes back to the seminal work by Robert Smithson, Hotel Palenque: a slideshow of a half-constructed hotel in Mexico, narrated by Smithson, in which the period of construction has been so drawn out that it exists in a state between construction and ruin. I think this idea is a constant in my work, and is very prevalent here.

In the gallery in Torino there’s a dark humour towards this idea of an archeology of the recent past, which is actually an attempt to plot an archeology of our political present. Among the more visually seductive objects within the exhibition are the classical columns cast in plaster, which we cut from the building. In their state of ruination they remind me of visiting Palmyra back in the 1990s, and the sense of beauty that a ruin can have. There’s an idea of the fracturing of economics and politics, but also a more physical fracturing. These things are feeding into my thinking whilst I’m making the show.

** What did fascinate you the most in Palmyra’s area?

MN: When I was at college in the 80s, I traveled to Turkey. I returned again in the early 90s, and in that period I also went to Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia. I became quite obsessed with this region of the world. The reasons for my interest are probably multiple, but I think one of them was my position as being British and from an incredibly colonial, imperial past, with a history around the idea of the exotic and exoticism. I was interested in my position within this lineage, which had very much to do with the prevailing interests of the time, the cultural climate of talking about ‘other’ cultures and the histories associated with them. To try to engage with this discourse from my position was highly problematic at that point in the 80s, but it was this aspect that intrigued me. As time moved on, I think it’s become less contentious as the world has been deemed ‘globalised.’

I’d been brought up in the countryside in the centre of Britain, I hadn’t traveled abroad at all except a French exchange in my teenage years, so my first trip away, to the east of Turkey, was shocking. It had a similar effect to that of intoxication somehow: the sensations of sounds, colours, heat, food, smells, it was so intense. I think it laid the foundation for trying to make work which somehow captured this experience and dissected it, retaining the history which underpinned it but using the tangible sensation of it too.

** What do you remember about the cultural climate of that period?

MN: In many ways what I experienced seemed very much the antithesis of the culture I’d been brought up with. The increasing secularity of British culture was very much at odds with the constant sound of the call to Mosque, something that seemed to underline the importance of religious belief that existed in these countries. I suppose it was a political awakening in many ways: whilst speaking with young people – men – in Pakistan in 1995, it was very clear that a young generation was becoming very antagonistic to the West, believing that there was a conspiracy against them as Muslims by the western world. If I had been a teenager living in Pakistan in the mid 90s and I was looking at what was going on in many places, such as the Balkans, or in Chechnya, or the constant situation of Palestine, I think I could have believed in a conspiracy, or plot, against the Islamic or the Muslim world.

** That was before the internet.

MN: I think the internet in many ways aggravated the process. Here I’m saying that I can understand this, I’m not justifying it. When I was at college, I remember watching a favourite film by the incredible partnership of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. The film was about a British and a Prussian soldier: they meet before the world wars, they become friends but are estranged through warfare, meeting sporadically through their lives. The narrative of the film is about the shift of warfare, from something that at the end of the 19th century was somehow played like an orderly game of chess, to the onslaught of the Second World War and the Nazis, where you see that any idea of rules, or decency – as misguided as it might have been – are gone. I remember watching it and thinking that the next world war would be just a state of constant terrorism all around the world. One could make a legitimate claim that we are in that state now.

** Where does the name The Amnesiacs come from?

MN: I wrote a proposal for a residency in Berwick-upon-Tweed whilst on a train to Budapest in 1996. I wrote it as a science fiction story. I took a character from a J.G. Ballard novel, and I transposed him into a structure borrowed from Solaris by Stanisław Lem. The character was a loner, a beachcomber, and I tried to imagine him collecting the debris from the coasts of every continent and viewing them as a language that had been thrown out by the oceans, almost as if they were intelligent entities that were trying to communicate with us through this debris. It was a strange mixture which also drew upon the Tarkovsky film Stalker which was taken from the story Roadside Picnic (Arkady and Boris Strugatsky). But when I arrived in the North East of England where the residency was based, the first weekend my friend Erlend Williamson and his girlfriend, Ania Rachmat, an Indonesian-Dutch artist, were coming to stay but they never arrived. Three days later we got a phone call. Erlend had fallen whilst climbing and died in Glencoe, Scotland.

So I spent the next six winter months on the edge of the English-Scottish border – it was a hard time. I had to deal with this loss, we were really close. I became very interested in Lem and the Strugatsky brothers, I became interested in them through the idea that whilst writing during the Soviet era, science fiction was used as a low-brow fictional genre that could bypass the censors of the time, criticising the state and commenting on the human condition. I decided to dumb down the narrative in a British context. I chose the British biker genre of the early 70s, which is a very niche market. I thought that I could attempt to use it in a similar way, to somehow talk about the social and political issues in Britain in the 90s. I liked the idea of a sort of white rural underclass that listens to heavy metal, existential bikers without bikes, and it seemed perfect for this. But when Erlend died it made it more complicated, because at the base of the narrative of Solaris is the idea of loss. Chris Kelvin, the main protagonist, is haunted by the return of his dead girlfriend who is a hallucination made real by the sentient ocean of the planet Solaris.

In a way, the fiction became real for me, in terms of this sense of loss at the heart of the project. So, rather than emulating this idea, I was actually going through a real sense of grieving. To come back to the question, I think I was watching a Hal Hartley’s Amateur, and I decided amnesia was the closest expression to what I felt, of the loss of somebody so close to you. Because you’re still existing in a world where everything appears to be exactly as the world you remember always was, but it somehow feels completely different. If you imagine a ricochet, like a bullet, it has a certain trajectory and then it hits something and it goes off at an angle. In a way this seems to be a state that I could equate with the idea of amnesia. I would imagine that if I had amnesia, I’d occasionally get a flashback, a glimpse of the life before, a life before the death of someone close. So I decided to invent the motorcycle gang called The Amnesiacs, which have no bikes and have no bodies, but were searching among these debris from the sea to try to make sense of life, death and the manmade world. Interestingly, I was thinking about The Amnesiacs in regard to the rise of Brexit and Trump recently. In a way, the idea was that The Amnesiacs were born out of the Gulf War, in a similar way the Hells Angels were born after WWII, and the Bandidos came after Vietnam. They were veterans, predominantly, but not always, with an assumption they were white males from the disenchanted working class.

** It’s interesting to talk about your work in this particular period, where you can sense a tension between fiction and reality, and a sort of swap between them. In your work an overlap between the two is always present.

MN: The reason why I’m more successful now than I might have been, is because of one work from 2000 called The Coral Reef, again borrowed from Stanisław Lem, Italo Calvino and William S. Burroughs. It was based mainly on the structure of A Perfect Vacuum by Lem, a review of non-existent books whose first chapter was a review of itself. I used this sort of literary structure to make a space made of multiple reception rooms, based mainly on minicab office receptions. By observing them in London, I always felt they were a front for something else, there was always something going on behind these that you never quite saw. The installation was a series of receptions, that led from one to the other, with mirrored rooms each depicting a different belief structure. The work invited you to become lost in a lost world of these buried beliefs. It now seems very pertinent in terms of the world today.**