As a person who has spent extended time in Rust-Belt America, I have come to think of malls as a thing of the past. Sprawling, abandoned buildings and endless parking lots that have become quite common outside of metropolitan centers are eerie monuments to a not-so-distant past version of America. An America that thought it would always be on top.

Sophia Al-Maria ‘s solo exhibition, Black Friday at New York’s Whitney Museum, running June 26 to October 31, is in many ways the nightmare of this past America, one with which the Qatari-American artist is familiar. Al Maria, who is also a writer and filmmaker, is perhaps best known for coining the term ‘Gulf Futurism’. It refers to the idea that the Arabian Gulf’s present state “made up of interior wastelands”, she writes about the concept in collaboration with Fatima Al Qadiri in Dazed Digital, “municipal master plans and environmental collapse [is] a projection of our global future”.

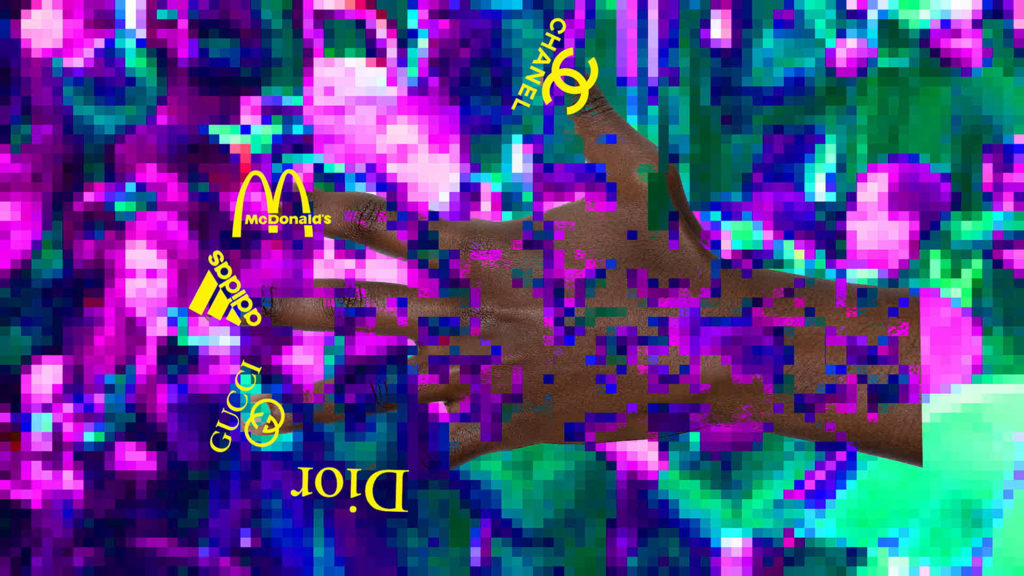

The small, but dense exhibition, takes on the idea of the mall in both the Gulf and the United States as “a weirdly neutral shared zone between cultures that are otherwise engaged in a sort of war of information and image.” Upon entry to the darkened room, one is immediately confronted by a wall of intense sound, coming from several ceiling-hung speakers, frequently emitting an intense, droning blast that almost makes the entire space quiver. Its intensity varies from said drone to a sort of eerie sci-fi music, to personal and fictional narrations, and is associated with the projection, which is the focal point of the installation. An elongated, vertical screen sits on a mound of sand and broken glass, strewn with wires and hundreds of broken phones and monitors, each flickering with a different image, tittering away in a glitchy jabber, that only emerges when the primary soundtrack is subdued.

The imposing situation of the screen recalls a space portal, or a ceremonial altar rather than a more traditional cinematic image in a dark room. By activating the architecture, and creating a new opening for interaction, those who enter the space are denied the luxury of passive consumption of that which it offers. Other aspects of the show preclude passivity. Nothing about this place is comfortable. The museum attendant wears earplugs, a mother who comes in to sit on the viewing bench almost immediately ushers her three boys (who are holding their ears) right out because the sound actually hurts. If you approach the screen, the frenetic flashing and snickering of the glitchy monitors distracts and overwhelms. I was not able to focus on it as a whole, often closing my eyes to listen, covering my ears to watch. The film projection is shot in dizzying angles, blurring, fragmenting, twisting and spiraling its images of vast, fantastical malls almost, but not completely, out of recognition. A digitized fun-house mirror that doesn’t let up.

As in a house of mirrors, where you turn the corner and see a warped figure, then realize it is yourself, there are startling moments of recognition in the installation. Dead ringers of our present and past “war of information and image” abound. Whether or not we recognize them as dead ringers becomes part of Black Friday‘s game. Some of these moments are more superficial than others. The exhibition’s title, for instance, references the American mall ‘holiday’; the day after Thanksgiving when people risk getting trampled in discount shopping stampedes in search of desired products — new technology or a hot kids toy. Is the mound of beached technology discards the refuse of such a consumer stampede? Or is this image a dead ringer for the infamous ‘electronic graveyards’, on the beaches of West Africa, here lit up as if by poltergeist to haunt us with ourselves? On one or more of the screens, one sees a flickering GIF of a teenage boy with his back to us, wearing a hoodie — an immediately recognizable, now reverberant signifier of invented white fear and actual black victimhood in America’s present epidemic of racial killings. This domestic information war is presumably situated in an Arab context, and thus takes on more international implications. Race isn’t just America’s problem. Indeed, on another video an image flickers showing a woman’s face, as though in a beauty advertisement, the hot pink words, “SKIN ELIMINATION MATERIALS”, flashing over the top. This is a grotesque radicalization of existing products, popular worldwide, designed to “lighten’ one’s complexion. Why not just eliminate it? Cheerfully jittering in the frame in bright colors, these images assume a pop/viral status, showing that in the end, they will be reduced to another tactic to entice consumers, only to be later discarded when they are no longer popular or ‘of use’.

The most deadpan moment of recognition in the exhibition, however, comes in the large-scale projection in two short scenes in the 16-minute film, which mirror each other — two sides of the same looking glass and the central moment in the loop. The scenes show a moving walkway, running in opposing directions, shot from above, an uncanny reference to the two towers of New York’s World Trade Centre. One, played in reverse, is shot over an artificial white background, the other, playing forward in time, has a black background. I was startled at how hard these images hit me — at this point I am so used to seeing this particular symbol used in critiques of late-capitalism, and to conflate it with Qatari mall culture feels so easy. And yet, I receive its gut-punch, perhaps because of the sound, or the undeniability of the reference, staring at me almost jeeringly as you if to say ‘you can’t un-recognize this’. The footage of the twin towers is an icon of the international war of information that we find ourselves in now. Situated in the ‘neutral territory’ of a mall makes it no less powerful, perhaps as testament to the incredible force and omnipresence of nationalist propaganda in architecture and the mainstream media. That I am relatively powerless against this image is a jarring revelation, and this particular moment in the film hones in on that. The walkways (and the people riding them) simultaneously ascend and descend (to where?), perhaps prodding towards the moralistic undertones that an picture of the skyscrapers now assumes. The scenes, though shot differently and showing different people riding the travelators, also move backwards and then forwards in time, two sides of a broken mirror. History repeating, but differently. An icon of our past-future dream-turned-current-nightmare and the inevitability of its repeating (not only in the looping structure of the film, but also our looping Gulf-futuristic present) is relentless and writ large.

Our ability to recognize signs from our past and our present is a major driving force in this exhibition. Much of this message is delivered through confronting, bombastic, hyperbolic and blunt visual and sonic strategies, isolating sci-fi malls, mainstream media images sent back to haunt us, a sneering narrator with a British accent. However a single, prolonged interlude voices the cruel realities of our ability and inability to recognize ourselves and those around us, and places it in a more personal light. A soft-spoken female narrator with an American accent, talks about visiting a mall in Doha. There they see some American military personnel in civilian clothing, recognizing that they were military by their “buzzed haircuts and combat boots”. Then a deeper moment of recognition: that one of the men was an old classmate of hers “from the ‘States”. She noticed that he did not recognize her at all in his ‘international distance’, admitting that she probably looked like one of the images they saw in ‘target practice’. And she, knowing her place, does not approach him. Had he also recognized her, how would this interaction have changed?

As much as its intensity has the power to repel and isolate its viewers, Black Friday uses moments of inevitable recognition to lure us into its reality. The exhibition prods us to recognize our past in this present moment. We can leave it, showing a present-future which might read as an apocalyptic, sci-fi, futuristic fun house, but it will follow us because it is already inside of us (if only we would recognize it). It is buzzing in our back pockets, flickering on billboards and screens, and in the dark recesses of our own identities.**