David Turley’s artistic practice is compulsive. Genetically predetermined to hoard and unbound by any single mode or medium, he follows the story of his collected materials faithfully, even when they lead him across the world, enticing him to transplant his life in pursuit of one beguiling tangent.

After a prolific eight years showing his sculptural installations across Australia and a successful long-term collaboration with Korin Gath (D&K)in Tokyo, David, like so many before departed his remote home town of Perth, Australia for London. Through all of his works run notions of memory and broken narrative, whereby forgotten, left behind or disposed objects offer up their obscured histories to become enmeshed with his own. By doggedly researching and reconfiguring these ready-mades, David uncovers new stories that then trigger further exploration. What’s fascinating is the shift that occurs between the artist’s elevation of these objects and the objects then shaping the artist’s own life trajectory.

In a scenario not entirely dissimilar to Indiana Jones’ search for his father in The Last Crusade, it is one man’s diary that led David oversees on a pilgrimage through England and Eastern Europe. Only, instead of the Holy Grail, he discovered a rich tapestry of anecdotes connecting everything together. With the final outcome of the yet-to-be-titled project being exhibited at The Royal British Sculptors Society later this year, David caught up with aqnb to take us back to the beginning.

aqnb: I guess we should start with diary you found?

David Turley: Yeah, well, the project started in Perth and it came about because of my bad habits of collecting shit. The deceased estate auction house was a favourite… it’s kind of sick really, but I always felt that I was giving things a new life as opposed to people who were just buying them to resell. There were always the antique dealers there, and you got to know them because every week the same guys would be there

aqnb: So you were re-imposing sentimentality into other people’s ephemera?

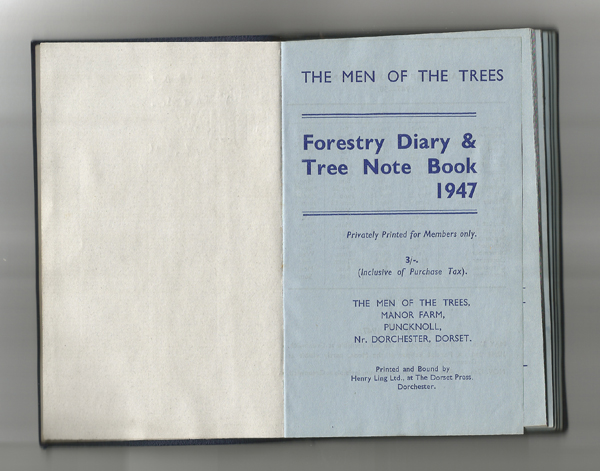

DT: Well, they were just getting them to sell them and I was getting them because they were beautiful and because they carried these histories. But I ended up buying this lot of stuff, which was just an old leather suitcase and some paperwork, just personal documents, but there was one photograph and this diary, which I’d wanted straight away because I’d been collecting diaries for years. The minute I opened the diary I thought, ‘well this is something nice’. There was stuff that was linked to my life straight away, addresses in my neighbourhood. So there’s this guy who kept this diary and he’s moved from England and come half way across the world and ended up just around the corner from where I walk every day.

aqnb: Is there some voyeuristic intent there – the thrill of peeping into a strangers world?

DT: I don’t know. It’s a fascination, I suppose. I’m not sure I’d go so far as calling it voyeurism…

aqnb: Have you ever stumbled across something that’s too private to include in your work?

DT: Yeah, I have found some strange things, little books that have peoples private writings… weird little leaflets for their next psychiatrist appointment. But in any piece I’ve ever done, none of the names are really revealed. With the diary project I’ve tried not to use the full name; it’s just Arthur. It’s really about my connection to this man and where it leads me. There’s this parallel investigation going on.

aqnb: You’ve said in the past that your work has a life of its own and you just try to keep up, which makes me think of religious belief, that some greater power might act through you.

DT: Yeah, that’s sometimes how I feel about my work; the classic thing of channeling… without all the hippy connotation bullshit. I find with the work, it really does lead on by itself, whether it’s me walking down the hill collecting pins…

aqnb: I saw you stop on the hill and pick something off a tree.

DT: Yeah, I had an urge [produces rusty stud pin from his pocket].

aqnb: David, that could make a hole in your pocket, or your leg, it’s not a very practical habit!

DT: Yes [laughs and shows a large tear in his trousers]. The work kind of leads me. With the diary, that was the whole thing. It was like, ‘well here I am, I’ll just simply walk the streets he walked’. The last diary entry he wrote was when he arrived in Australia and he says he went to his house in Maylands and so I went to the address and I discovered my own connection to that place. I used to walk that street very often when I first arrived in Perth, to visit a friend of mine… and across from this house was the oval were we used to go at night time to kick the football around. So it unlocked this memory from my own life and I started researching the oval, which was the home of the wonderfully named blind cricket team ‘The West Australian Venetians’. And so I ended up contacting the team and organising a cricket match. That was a really lovely project, to have a game of cricket on that oval dedicated to this guy – and nothing more than that.

aqnb: A happening, creating another memory

DT: Exactly.

aqnb: So a lot of it was triggered by your own memories in Australia but I’m wondering if you’ve found it hard to identify signifiers in the UK?

DT: Well, it was all in the diary. That’s what bought me over here. I’d followed everything I could at home and I thought, ‘why don’t I take this one step further and go to the other side of the world just to see where it leads’. But I started painting, of all things, places from the diary. There was a house in Cricklewood for example but the next day the painting would come from my own world, something in the newspaper I’d picked up. So it never really changed by coming here.

aqnb: Is that because you are reappropriating symbols from existing social constructs; religion, sport…?

DT: Yes. I’m more interested in what the symbols are to other people than what they are to me, even when I reference my own memories of growing up, or to do with my grandfather… there’s a distance there, you know? To take a step back and look at these things and it’s very strange.

aqnb: Those silent, unwritten social contracts we all go along with?

DT: Yes! But don’t really stand back from and question! The religion thing is in everything, I can’t avoid it. Belief, faith, it’s the essence of everything – a none-belief is still a belief. So that thread runs through everything I do. And in the diary, again it’s layered, every Sunday without fail he’d ride to mass.

aqnb: Where did the diary lead you once you arrived in England?

DT: It took me to Dorset where the book was actually made. The Dorset Press have been operating for 140 years or something and they’re still running, so this original ‘Men of the Trees’ book; the diary that Arthur wrote in, was printed by them. For me there was this really lovely idea of going back to the origin of just the physicality of the book. And I looked into whether this place could print the same book with Arthurs writing in it… they thought I was weird because I only wanted one copy. You could print thousands of copies of this thing and it wouldn’t really make sense. The act of coming across the world just to produce this one thing, this is my contribution.

aqnb: So how will the book live on?

DT: It’s going to be a sculpture, a structure, which actually displays the book. There’s also going to be another book printed, which is all of the nonsense that’s happened surrounding it.

aqnb: Your own diary?

DT: Yeah, I suppose. The paintings I’ve done, sculptures I’ve made, there will be this little publication with all of that in there and some text, where I’ll probably talk about my bloody grandfather again. So the final presentation will be of the two books embedded into this one structure that comes from all these things I’ve been looking at, whether it be shrines in Eastern Europe, or the bell tower at St Joseph’s Church in Northam,[Western Australia]. Having gone back there recently for my grandfather’s funeral, having the bell ring again, which rang 20 year ago for my grandmothers funeral and which I used to ring as a kid as alter server… So the structure I’m working on is a steel and concrete thing to hold these two books.

aqnb: With the finality of your grandfather’s death and your residency next month in the Ukraine, where he grew up, is it all culminating to some end point?

DT: No because it’s opened up so many new projects. Going home for the funeral, I had to go through all of his things because it was really hard for mum. So here’s me sitting in his bedroom, you should see some of it, there was this ring he used to wear when he was young, his compass and binoculars from the war.

aqnb: What did he make of your art?

DT: He didn’t have a clue. I don’t think it made sense, that kind of equation of art and who we are. You know he was 90, coming from Eastern Europe and going through all the things he did. Of course, he knew classical painting, but contemporary art, my god! A month before he died he said to mum, ‘make sure David get’s this box’, which was the box he made to ship all of his possessions to Australia. But he didn’t know about the stuff I’d been doing and the last thing I made before I left Perth was a wooden box, which was a copy of a box I’d found on the side of the road…

aqnb: Did you get that from him? Was he a collector?

DT: Yeah, being Eastern European and going through the depression he never threw anything away. He’s a carpenter, so every piece of wood he ever found is at the house. Of course I’ve been going, ‘dad you can’t throw any of that stuff away’. There are so many layers there. There’s the box he made, the box I made and the box this stranger made. And the layers of where he grew up. When he was eight years old he was involved in pulling down this wooden church, which was shipped to Lviv; where I’m going for my residency. So there’s this huge three-domed church, which I’m going to and, as a kid, he went to. The next show’s already coming together. So to answer your question, I don’t think it will ever end.

Dave Turley will be Artist in Residence at The Museum of Ideas in Lviv, Ukraine in October 2012 and exhibiting bursary holder at The Royal British Sculptors Society in November 2012.