share news item

A planetarium of loss + grief: David Blandy sifts through the macro + micro of The End of the World at Seventeen, Nov 2 – Dec 16

share news item

“When I say my character is fictional, I mean it’s based on all the negative attributes that I see in myself, so it is fictional in that it is based on a caricature of what I already see present in myself” explains Patrick Goddard about his role as a video artist/documentary filmmaker in an interview at my house, “In that sense, it’s a parody or a confession of my worst attribute.”

Here to discuss his recent solo exhibition at London’s Seventeen, which ran April 23 to June 3, Go Professional is presented as a trilogy, where each 30-minute video occupies its own room, an individual narrative unfolding through documentary-style language. Pre-scripted and with a GoPro camera attached to his head, the artist engages with the subjects in a fictionalized one-on-one scenario. Both playful and politically charged, the work highlights the complexity of one’s position and the didacticism of critique through a humorous undermining of self.

As you walk into the space, the first room you enter has been transformed into a half-ass wilderness; the floor is covered in dirt and there are logs dotted around for the viewer to sit on. An old rusty barrel and a stack of crates become shelves for speakers; ‘Gone to Croatan; (2014) features Adam Burton, an old friend of Goddard’s who opted out of society to live in a cabin in the woods. Cynical of the character’s attempt to live by his morals, Goddard positions his camera to become the judgemental lens to his inner thoughts, ‘scoffing’ at any hint of hypocrisy and highlighting the fine line between bullying and critique. The second room, playing ‘Greater Fool Theory’ (2015), is lit red and stuffed full of office chairs; the installation has me laughing before I’ve even seen the work.

Each film is varied in relationship dynamics, moving between the behaviours of bullying, to banter, and opting out of competing completely in the final one. They all share an underlying dissection of authority, turning the focus of subject around onto the artist himself, to question (as Goddard notes) “the presumption that you are somehow outside of the situation in which you are talking, discussing, viewing or observing.”

** Can you expand on the role you play in your work?

Patrick Goddard: I’m playing myself, but I’m playing a version of myself. I’m still Patrick Goddard ‘The Artist’ but full of naiveties, bullying tendencies and manipulativeness – essentially a version of myself minus redeeming qualities, hopefully. So I’m kind of performing this parody of a liberal bourgeois artist, which is part of who I really am, but I am definitely using myself as an example of this. So hopefully in the films, it’s not so much that I’m following around a subject. In many ways the subject, certainly in the first two films, becomes the character of this presumptuous, at times self-righteous, artist character who’s also a bit of a bully, a bit of a would-be-alpha male, which I kind of wanted to poke fun at – at certain documentary, or ethnographic, or even artistic stances of removal.

PG: In ‘Gone to Croatan’ with Adam, I knew instantly with the concept that he would be perfect, because he’s softly spoken and charming and various other things, and the politics aren’t that far away from his politics, and actually my politics, as well. There are moments of things that aren’t scripted, cause he’s quite a charming, funny guy. Sometimes he’d fluff up the script or get it wrong, and then just go off into some sort of surreal tangent, which I then keep in the edit.

Some of the characters are based on having chats with people I know who work in finance, or not necessarily friends but, you know, your mate’s new boyfriend who she brings around for dinner one day and turns out he’s a banker, and you get drunk and pin him in the corner and ramble at him and sort of trap him. Then I base a lot of the characters or things that were said, on those moments, which wasn’t always necessarily deliberate research for the films.

** How did you get to this place of making in your practice, a place of almost anti-making. Did it come from a place of dissatisfaction with hearing your own voice and critique, or being embarrassed with being an artist?

PG: It started a few years ago with some other artworks – I believed in all of these things I was writing about, but this sort of self-righteous pomposity of the voice that I would have when writing, I kind of wanted to keep that to a degree but also poke fun at it. So rather than toning down the didactic tones of writing, I would bring in a second voice that would decry the pomposity of the primary narrator, of me. So that happened in a film I made in 2013, ‘Free Radicals,’ which actually had Adam as the second voice, so there’s a kind of free verse poem and I got him to do the voice for that, who heckles my character.

** I found myself trying to figure out your position the whole time in ‘Gone to Croatan’ but it’s a nice tactic because our inner judgements are already being played out by you, they almost cancel them out.

PG: Adam’s character keeps coming up short, he’s not equipped to live in the wild, and from the viewer’s point of view, you could quickly denounce him as being simplistic or naive or whatever else, but I found that to be too lazy a conclusion the audience would take. So instead of saying, ‘no this guy’s actually really great and he’s actually trying, what the fuck are you doing?’ and holding him up as a hero, I try to embody the would-be criticisms of the audience in this kind of smug, city-slicker, supposedly liberal but essentially a bit self righteous and a bit dismissive filmmaker. When Adam says things like, ‘oh yeah, well last winter I went back to my mum’s house ‘cause it got cold,’ if my character didn’t say anything then the audience might be like, ‘oh it’s like that is it.’ Re-scripting that would-be criticism into the film and into the mouth of quite an obnoxious character. When I say what the audience are all thinking, ‘bit of a middle-class luxury isn’t it’ then hopefully it kind of holds up the laziness of criticism in relation to Adam’s political endeavour.

But I was also fascinated at the time of how people who are making no particular effort to live out a kind of politics or professed ethics are so quick to denounce anyone who tries for being naive, or like, ‘oh you know it can’t work or it can’t be effective ‘cause of this, that and the other’ are always quick to point out the impossibility of living an ethical life. I wanted both those characters in the film. My own political views are probably closer to the portrayal of Adam in that film.

PG: I’m very vocal about my politics and my ethics outside of the artwork, or amongst friends, or in an expanded art practice in talks, or in other public roles. I think it’s obvious roughly where I sit in the films, but the character in play doesn’t necessarily have the lines I agree with. So I may even give my opinion to another character, the character’s in the film might alternate with who gets the best line or who gets the lines that I agree with. You might agree with some of the things Sam says. At first, in the script, my character had all those lines, and I thought, ‘no, this banker guy is just seeming too one-dimensional, and too dislikable, or too apolitical. I’ll give him some of the seemingly left-leaning lines,’ and then I just kind of literally take the lines from one character and give it to another. And I know in the end it seems like they’re up against each other but they’re not.

** You make both characters hypocritical in a way; is that something at the root of your work – the hypocrite?

PG: I think a lot about hypocrisy, and I think hypocrisy gets a really raw deal in society and I think people are very quick to criticize the hypocrite. There are different types of hypocrisy obviously, there’s hypocrisy where somebody seems pure in word but makes no effort to back that up and that’s obviously problematic, but there’re also hypocrites who are trying, but fail, or trying and succeed sometimes, and fail other times, or who have ideals but have to compromise for various reasons. It’s better to be a hypocrite who actually tries to live an ethical and political life and falls short sometimes than somebody who recognizes the inevitable hypocrisy of the ethical project and just doesn’t even try to make or have ideals.

Because of Adam’s character in Gone To Croatan, what I really want to get across is like, at least he’s fucking trying. It’s so easy to point and laugh at his character, but like, you know he’s trying. This idea that once you are born into consumer system or just liking Pringles say, or salty food, or whatever it might be, it’s very difficult to just suddenly cut it out, and go live in a hut in the woods without any withdrawal symptoms from contemporary metropolitan consumer life, “once you pop you can’t stop” to a degree but like, you know you can try and stop.

The second film is all about evading accountability, so Sam’s character, this quantity analyst working in the city, in some ways he seems to come out winning all the arguments, but he really, in my opinion, doesn’t because the main formula for writing the script was that he’s never accountable, he never answers the questions. If my character has a problem with the ethics of the place where he works, instead of responding to that he goes, ‘oh yeah, well you think you’re so fucking good? We can’t all get sent to art school.’ He’s constantly avoiding ethical accountability, in a very clever and kind of natural way – ‘oh, we’ve all got to get a job, so is the secretary also complicit, is Rob the sandwich guy?

** Do you think the language of critique is irrelevant?

PG: I think portraying a critique makes it sound politically illustrative or academically illustrative, which I think a lot of work can be and often can be a bit boring, didactic.

I don’t necessarily want to criticize contemporary art and I do in the films a bit via the characters, or going to Frieze Art Fair. While I do think a lot of art is shit, and so does everyone, I would say the profession of art is of course smirched by capital, and money, and art fairs, and all the rest of it. The idea that once the artwork leaves your studio it’s somehow no longer your responsibility…I’m perhaps more critical of, rather than perhaps what other people choose to make work about.

**Yeah I guess I was referring to critique as a form of nihilism, where there’s no route out or a feeling of being stuck. Even though there is this aspect of being in a ’whirlpool’ with your work, you manage to somehow bypass nihilism in a nice way. In a way it feels hopeful, it lets in room for faith or belief. Would you agree with this?

PG: The gap between faith and nihilism – both seem to be crystallized opinions. Faith is belief in something outside of, that can’t be confirmed. I don’t have some sort of consistent faith, or even necessarily some consistent ideology or underpinning philosophy that is at the driving heart of my practice…

Marianna Simnett is presenting solo exhibition Lies at New York’s Seventeen gallery, opening November 20 and running from November 23 to January 22.

The London-based artist works with film, often weaving disparate yet connected narratives together to explore the contaminated body and the visceral reality of identity. Rooted in layers and histories, there’s often a violent undertone to most of Simnett’s work; a balancing act between constraint and subversion.

Simnett first screened the new film as part of the Serpentine Miracle Marathon (2016) in October and had a solo exhibition Valves Collapse at Seventeen Gallery London earlier this year.

See the Seventeen gallery website for details.**

share news item

The Morning uber, evening oscillators group exhibition is on at London’s Seventeen gallery, opening November 17 and running to December 17.

“Weird, he never really rested, he said, the light and the consciousness of the waking world didn’t let him feel properly rested. And if your productivity and consumption are set to night, everything changes, he added. I felt, I knew what he meant.”

Organised by Attilia Fattori Franchini, the show brings together work by VALIE EXPORT, Eloise Hawser, Sebastian Lloyd Rees and Hannah Perry. The four practices unite to explore “urbanism, negative spaces, fragmentation and dream-states” and respond to deeper narratives in our contemporary, consumer culture.

See the Seventeen gallery website for details.**

share news item

The Lonesome Wife group exhibition is on at London’s Seventeen, opening September 30 and running to November 5.

Organised by Attilia Fattori Franchini, the exhibition includes Lisa Holzer, Isaac Lythgoe, Victoria Adam, Adriano Amaral, Noah Barker, Luis Miguel Bendaña, Patrizio di Massimo, Justin Fitzpatrick, and Vanessa Safavi.

The exhibition takes its name from American novelist William H. Gass’ 1989 book Willie Masters’ Lonesome Wife. The press release includes an excerpt that states “…there’s nothing female about a column of air, a gall on a tree – surely both, like bloomers on the swing’s seat… so I’m a spiky bush at least, I like to think, knotty and low growing, scratchy though flowering, a hawthorne would suit me”, alluding to the themes of the show.

Using text as a starting point, Gass creates “a parallel between a concrete use of language and the female body of Babs Masters, both employed as tools of persuasion, absorbing the reader-viewer in a game of intimate eclipse and revelation”. The exhibition explores seduction and how it can serve as narrative tool as well as “an antidote to boredom and disinterest”. Exhibited works hint at the body, the physicality of text and the linguistic capacity of objects. They move between form, process and content, to be read or to be felt.

See the Seventeen website for details.**

Luis Miguel Bendaña, ‘Blush On A Man’ (2015), Detail. Courtesy the artist.

share news item

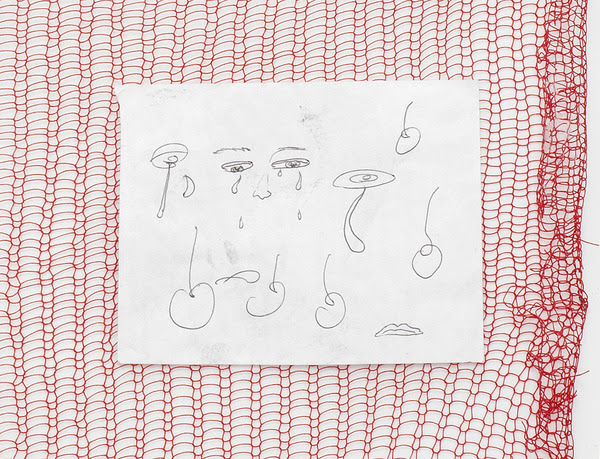

Marianna Simnett’s Valves Collapse solo exhibition was on at London’s Seventeen Gallery, running January 15 to February 20, 2016.

The installation featured the London-based artist’s most recent video ‘Blue Roses’ (2016) —about which aqnb interviewed Simnett in 2015 while it was still in production —in one room, and a sound and light installation called ‘Faint With Light’ (2015) in another. As described by the gallery, the Valves Collapse presents “the body in states of transformation and distress, blood, surgery and fainting”, with work that stimulates the viewer’s sensations.

According to Seventeen, ’Blue Roses’ alternates between three main locations: a bright, sterile operating theatre; a murky blue netherworld representing the area under the skin at the back of the knee; and a parallel world, filmed in a real-life Texas laboratory, in which cockroaches are subjected to invasive experiments that hijack the insects’ nervous systems to remotely control their legs. Some of the spaces seem ‘real’ —the hospital scenes, significantly —while others resemble fairy tales, paranoid hallucinations, or cinematic interpretations of the protagonists’ traumatised consciousness.

Meanwhile, ‘Faint with Light’ is an installation work that in its pared-down intensity both simplifies and amplifies the themes and moods of Simnett’s film trilogy, where the artist repeatedly fainted by forcing herself to hyperventilate.**

Exhibition photos, top right.