Candice Lin and Patrick Staff presented collaborative project LESBIAN GULLS, DEAD ZONES, SWEAT AND T. at Los Angeles’ Human Resources which opened May 4 to the 21, 2017.

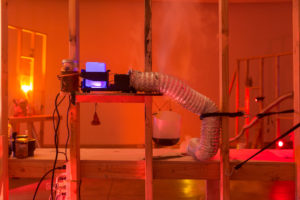

A framed wooden structure in a hexagonal layout was placed in the centre of the room; a reference to “the chemical compound of benzene, part of a phyto-hormonal change that occurs during the aromatization of certain plants.”

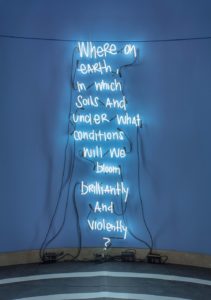

An exploration of botanical knowledge and chemistry, the installation became a ‘slow forming cloud’ that proposed both a cross-pollination and infection between “bodies, ecosystems, and institutions.”

Both artists’ practices are concerned with ecology and botany through a queer re-reading, and invite the viewer to “to lose the illusion of their bodily boundaries and float within the influence of a hormonal mist.” Read our interview with Candice Lin to hear more about these ideas.