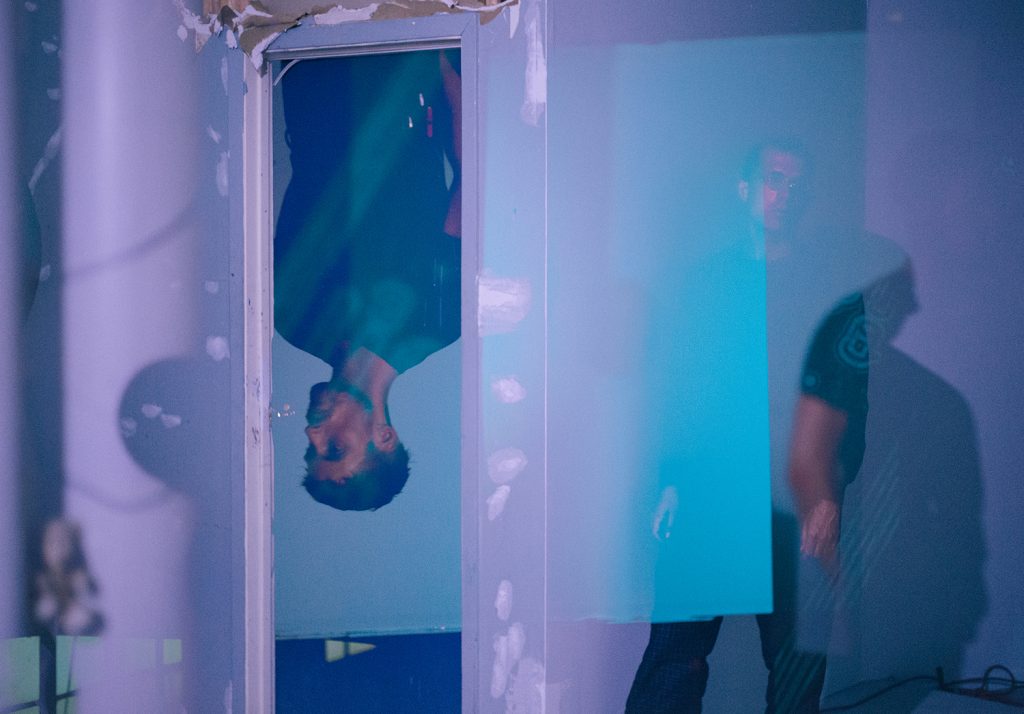

In the hot moonlit room of a role-play festival in Zagreb, flute calls melt into gothic trance while two figures move through space—hunting, playing, calling, cruising. As bass lines float through open windows, a delicate web of choreographed sounds and gestures emerge. These momentary encounters are marked by operatic crescendos and camo gear.

“We’re interested in how shifting linguistic systems can undermine meaning production,” explains Belgian composer and performance artist Billy John Bultheel as he sips coffee with American artist Alexander Iezzi on a Croatian terrace. The duo has produced three iterations of their concert-based performance ‘Shadow Hunter’, which premiered at Zagreb’s Galerija Močvara in July last year, with two more iterations since surfacing at New York’s No Moon and The Watermill Center.

Employing the archetype of the hunter, the performance encompasses an unlikely assemblage of military survivalist aesthetics and music influenced by Venetian Baroque composers such as Willaert and Monteverdi and their construction of multiple voices or sources to produce a single sound; early versions of synthesisers. Bultheel draws on his research in Early Renaissance polyphony and electronic composition to develop a layered ensemble with profound rhythmic and melodic language. In observing the Berlin-based artist’s dark soundscapes—like the recent ‘Signs of Invasion’ or ‘Spat from My Mouth: Piano Concerto’—our senses are overwhelmed with the echo of choirs and dungeon synth; a mix of ambient sound and black metal. These pieces are sublime in effect, at once violent and uplifting. Bultheel’s work as composer of Anne Imhof’s recent performance trilogy Angst, Faust and Sex—a series of durational operas contemplating violence, desire and power—is indicative of his wider interest in spatial notions of sound that poetically give shape to social structures.

In Bultheel’s collaborative compositions with Iezzi, sound reveals a delicate sensuality through the exploration of queer resistance; the negotiation of desire outside of financial value systems. Drawing on his research of identity in relation to facial recognition technology, artist and theorist Zach Blas points out that when queer politics gain visibility they become identified in recognisable ways. However, through mainstream co-optation they often lose their radicality through such visibility. A key form of defiance therefore becomes in-visibility. The ‘politics of escape’ Blas proposes is a building of conceptual weapons against such fixed identities. In ‘Shadow Hunter’, unrecognisable sonic gestures take on significance. Deafening instrumental hymns, operatic screeches, echoes of apathy—these become weapons to escape recognisable forms.

“Sometimes we get along very harmoniously, but that doesn’t produce the most interesting work,” hints Iezzi, as the two of them unpack a lunch of fruit, gherkins and hummus; he and Bultheel are used to these fluid exchanges, playfully challenging one another. It is precisely the tension between their practices that results in the duo’s tangential landscapes. While Bultheel grounds his research in spatial music composition, Iezzi focuses on notions of social, chemical and psychological transformation. His recent solo show at Brussels’ Kantine poses the question, “what if pilgrimage could be thought of as a scurrying?” It examines the concept of beatification, a religious honor in which the Roman Catholic Church declares a dead person as holy. Voodoo doll sculptures of the beati adorn the space, devoting their lives to the undeserved; transforming sour to sweet. Vinegar stenches with bags of fermented fruit—will the sweetness of the world soon turn sour? Iezzi’s uncanny conceptual framework conflates chemical and religious meaning, looking at the ways in which intentions are unravelled and remade. His thoughtful narratives are often paired with experimental sound-based elements, ranging from classical percussion and harpsichords, to gabber and screamo Aerosmith remixes. Sound and experience are reshaped ad nauseam; becoming at once melodic, bitter and harmonious.

In their collaborative practice, Bultheel and Iezzi combine their respective research to create transitory encounters based on processes of undoing, remixing and remaking. The act of reconfiguring sound and gesture becomes a stratagem to resist the violence inherent in linguistic and choreographic structures. As they prepare to release their first album later this year, the duo discuss their ambitions—from fighting discursive captivity to operating outside of marketable machines—and envision a world in which poetic devices become artillery against weaponised meaning.

**In Shadow Hunter you draw on Monique Wittig’s The Lesbian Body (1973) as a point of reference. In this text, Wittig notably splits the French impersonal pronoun j/e to signify a multiplicity and resist linguistic (male) domination. It is also extremely sensual.

Billy John Bultheel: The Lesbian Body is a kind of poetic case study on affection. Wittig dissects her lover’s body through intense visceral descriptions. Her obsession becomes this poetic exposition. For us, that is a very interesting tool; to see how we can shift and utilise the archetype of the hunter and approach its subject from a poetic perspective.

There is this passage in which [Wittig] portrays two sphinxes hunting each other—but you’re not really sure if they’re hunting, making love, or exploring a more sensual connection. The entire poem is constructed around the two sneaking up on each other and then disappearing once they touch. This poetic landscape that lies between vigilance, affection and violence is an interesting starting point to making music and performance.

Alexander Iezzi: The gaze shifts during the performance. At times I’m watching Billy, at times he’s watching me. [We are] evading domination by reversing roles over and over.

**There is a strong emphasis on this continual game of reversal. Is this dynamic also present in the way you compose sound?

AI: I think there is most definitely a conscious act of reversal in our entire collaboration. Some of our best ideas have come from one of us taking another’s idea and really messing it up, or really pushing it past the limit that the other set for it. It sounds violent when put into bodily or affective terms, but when working with aesthetics, it is one of the strongest things a collaboration can produce.

BB: From building physical instruments together, to composing in an almost cadavre exquis style, to interconnecting patchboards on analogue synthesisers or even writing poetry to one another. We keep the dynamic of our collaboration active by constantly reversing roles and shifting the comfort zone away from one’s personal practice into the other’s.

**Your compositions can be described as baroque in style, yet how does spatiality interact with these sound-based landscapes?

AI: Both of us have the potential to be quite maximal in [our] approach to music. I spend a lot of time building up layers of sound and cutting back into them and reorganizing them. I think this level of detail […] comes from our two practices combining.

Spatiality becomes increasingly important in this mixing. We’ve been using five-channel audio in order to fit all the pieces together and also to play with their movement around a space. It’s another way to build additional levels into the music: entering a space with a preconceived idea, and getting to stretch it out within a new context.

BB: I’ve been looking at medieval and baroque composition methods since my time at the conservatory, [which] made me understand music or composition as a machine-making practice. One where you can combine different musical elements and release algorithmic formulas to build complex sonic worlds. And rather than writing melodic lines over linear harmonic developments, a composer would create these complex relational structures that offer a spectrum of melodic and harmonic possibilities, almost more as an interactive score for their musicians.

I think Alex and I set up these kind of musical practices too, but we expanded this idea into multiple, interrelated disciplines. It’s setting up these creative worlds that we can improvise and play within. You could call them ‘baroque machines’. Some kinda weird steampunk idea of an instrument, an AI-controlled piano on a steam engine.

**What role does the concept of queer weaponry play in your work?

AI: This concept became an interesting entry point into the theme of hunting. Hunting is a weaponised practice and there is a certain violence built into that. We spoke a lot about how language can be weaponised. Is there a potential for language to resist bigger oppressive forces? Poetry evades normativity through the structure of language. It shows how you can use the tools from a given structure and reconfigure them to produce meanings that have a less determinate outcome.

**So linguistic systems embody their own set of politics. If words (as bodies) can resist servitude and domination, what is the role of an author?

AI: An [author] is not someone who necessarily has to deliver meaning. Artists can create a space in which meaning is freely open to peoples’ own encounters. An ethics and a politics can still have space to be free and move around, but give an entry point into the work rather than providing concrete meanings for it. This strict meaning is what we refer to when we talk about weaponised meaning.

**It’s difficult to resist the co-optation of queerness, particularly within the arts. What tools—linguistic, poetic or otherwise—can be used to this end?

AI: Once you name something, you fix the meaning. This practice comes from the market and capitalism, and this idea that you only become relevant or powerful if you define yourself as an artist with a political stance. How are you able to evade that categorisation but still have visibility? Being aware that queerness is consumed by the same normalisation that straight life is, through something like capitalism […] it feels more poignant to look up and see what these bigger structures are.

**It seems collectivity plays a role in this poetic reconfiguration, the battle of words and gestures against larger structures.

AI: Whether it’s two people collaborating or a whole scene, I think collectivity is a big part of resisting the capitalistic tendency to suck culture dry of its meaning. With collective solidarity you are able to create your own system (lexicon included) where meaning can retain its initial value.

BB: In a collective experience, there is a place for creating meaning with and for each other, a meaning that holds collective value. Contrary to living in a financial and political system that constantly renders ideas and actions meaningless, creating meaning for each other has almost become a necessity for us to survive.

Earlier, you asked us if we considered ourselves to be queer artists. My instinctive reaction was to immediately say no. This reaction baffled me for months. I didn’t understand why I was so quick to respond. We are subjects with a queer experience and we are people who believe in the queer project, and we are artists that work and challenge ideas in this field. So why did I not want to own up to this term? I feel the term ‘queer’ has become a [form of] branding rather than a political project. Its meaning has been captured and used as a way to promote artists or musicians, values that [in my opinion] have more to do with individuals becoming interesting market assets than the belief in solidarity on a larger socio-economic scale. The interesting part of being queer is that one does not have to comply to comprehensive descriptions, but rather can engage with actions, desires and agendas that are incomprehensible to the market system.

The challenge is [to resist] rendering ourselves empty while surrounded by aggressively empty value systems. Poetry and play could be mechanisms to do that.**

Billy John Bultheel & Alexander Iezzi are releasing their new yet-to-be-titled album in late-2020.

share news item