“The residency gave me the opportunity to experience this neighbourhood, which is interesting because it has many connections with the context I’m used to working in,” says Fabio Santacroce, speaking on a cold, sunny Sunday afternoon in Bermondsey, South London, chatting between steamy cups of tea and a bag of muffins. We’re here to discuss the exhibition Il Cielo a Calci (intro) at London’s Jupiter Woods, a one night event concluding his ten day residency at the space and co-organised with curator Rosana Puyol on March 24. The presentation also featured sound works by Kareem Lofty and Atièna alongside sculptural elements by Olu David Ogunnaike and Santacroce himself.

Santacroce is perhaps best known for his project 63rd-77th STEPS; a platform for contemporary art he created on a section of a stairway in his flat in Bari, where he invites artists from all over the world to exhibit in the space. And despite, or because of, the incongruity of the situation, many artists, including Amalia Ulman and Daniel Keller, have accepted, turning the staircase into a thriving display space and complicating the boundaries between private and public space, creating a forum for the experience of art that escapes the often self-imposed strictures of traditional exhibitions. Since its inception, the 63rd-77th STEPS project has grown considerably, and Santacroce has curated exhibitions on beaches and other spaces in Bari, as well as at Art-o-Rama in Marseille.

Santacroce’s own practice treads a number of aesthetic lines between installation and sculpture, found objects and handmade ones, as well as themes of universality, marginality, disposability and endurance. Jupiter Woods is located at the end of a long street in South Bermondsey populated by council flats, repurposed warehouses, and bustling churches. Just beyond the gallery lies the storied football stadium known as The Den, home to Millwall FC—whose fans bequeathed to the world perhaps the most notorious chant in the history of football: “No one likes us! We don’t care!” Such a social environment could seem an incongruous spot for such a robustly outward-looking practice as Santacroce’s, but he takes pains frequently as we speak to highlight the sense of connection to the local communities in which he found himself situated. He stresses the fact that, often, networks of economic solidarity develop where possible forms of identity might not necessarily promote connection. Sport and music specifically, Santacroce notes, bring communities across social and cultural divides together, however fleeting, and these moments of contact can become the basis for new modes of thinking, experience and self-definition. With these themes in mind, I want to explore his perspective on the roots of the exhibition and the ideas it seeks to present. I began by asking about the Italian phrase he selected for the shows’ title:

Fabio Santacroce: Il Cielo a Calci; it’s an Italian sentence that means when you kick someone or hurt someone, but in this case, you do it to the sky. This includes an impossible but subtle gesture of rebellion, not at any specific target necessarily, but rebellion more generally, and this approach, this feeling imbues 63rd-77th STEPS project. This expression brings this romantic violence, in a way. It comes from a letter that a friend of mine wrote some months ago expressing in such a beautiful way the huge pain coming from her awareness that she was going to lose her daughter. I was totally impressed by her words. I found this sentence so eloquent, and also, it seemed to connect to a larger dimension.

** I’m interested in the notion of interiority. There’s a different kind of interiority to a gallery space than there is to a stairway in a block of flats. Did these different forms of interiority play a role in the construction of this exhibition?

FS: I always found it a bit frustrating, associating the programme with being in a strange or odd location. That was never, for me, the main point. There was always the particular — or specific — space of the staircase being in a domestic environment, and the sense of feeling comfortable in the same way as when you invite people to your place. This encouraged me to focus on an ethical approach. Every time I was doing a show there, it was like inviting people to my place. I was very strict; I never wanted to introduce anything I don’t believe in or anything I don’t like. Also, it was about reflecting on peripheries, not just geographical ones, but also economic or cultural ones, and to trace a sort of generational mood, trying to find, in a specific local context, connections with different areas of the world where certain economic and political dynamics are the same. Being site-specific provides an occasion to reflect on the fact that in this specific period, we cannot be fully site-specific. We are really connected in many ways. So it was also interesting to trace these global geographies starting from a specific context.

** This connectivity you mention is obviously pervasive, not least with regard to market forces, which you’ve examined in other projects you’ve undertaken. Do you feel this form of connectivity, economic connectivity, is a major part of Il Cielo a Calci?

FB: I didn’t want to address these issues in this specific exhibition, but the reference to the market comes spontaneously with a programme, mainly because most of the artists I’ve been working with are now well-established. And this is interesting because reflecting on these marginal positions but also wearing a sort of mainstream dress creates a short circuit that I find interesting. as a way of experiencing and reflecting on market dynamics — which I tend to not demonize because I think there is no way of negating the importance of the market for the artist and for the circulation of art generally.

Personally, I didn’t consider the commercial aspect with 63rd-77 STEPS because I want to feel able to establish a relationship with the artist I’m inviting in a different way, as well as allowing for the artist to make something that could be limited through the market. Conceiving a work for being sold is different from considering a work just to create a cultural experience. Sometimes they can overlap, but I think in this specific case, I’ve found that most of the artists are able to deviate from commercial structures, and they were giving something to me that I found to be totally great.

** This exhibition feels quite topical. In terms of the imagery, was this specific set of images something you’d planned beforehand or did it emerge from working in the space and the city?

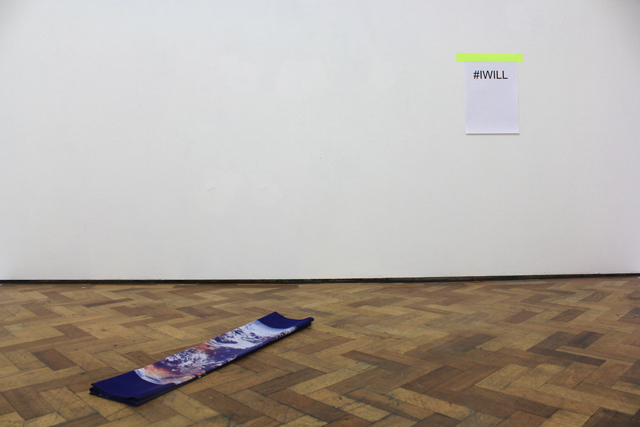

FB: For the exhibition, I’m presenting this piece using the image of George Michael from the album, Older, and these canvases were wrapped using these zip ties, so it’s a very subtle gesture referencing suffocation. Why George Michael? George Michael is obviously a pop music icon, but also he was a way for me to gently and ironically address a UK audience, and his recent passing. In the districts where I work, when his death was announced, people played his music every day, so it became the soundtrack for almost two weeks. Music plays an important social function in this district, as does football, and it was also curious that behind Jupiter Woods there is also this football stadium. But I don’t really do planning, I don’t consider my works planned, I create a kind of overlay that comes from everyday life. Also, being here gave me this impetus to focus on these details — trying to recreate these overlapping sensations that comes from experiencing the city, experiencing the context. This is one of the reasons we left the space untouched. This ceiling, for example, really worked well with the idea of the sky being kicked. And the footballs themselves are not fixed, so, during the opening, people were just kicking them around, and this was creating an interactive element that was also interesting to me. They were also creating a bit of danger too, subtle danger. Obviously, we didn’t want to hurt anyone but it was like the low frequency, subtle violence.

** Though this exhibition concentrates on your artistic practice, there are also elements of curation, particularly the inclusion of the work of your collaborators. Could you speak about why these works resonated with you or fit in with the themes of the show?

FB: For example, Olu constructs these stratifications of different wood from different parts of the world. He overlaps them and creates the panels, he constructs the layers. That was very interesting for me because it was a subtle reference to the many cultural and racial identities of peoples around the world, compressed into one place as one experiences in London. The reference to humanity compressed into one meter square has many layers of meaning, and the wood from the trees is one of the features of the terrestrial world that gets closest to the sky, naturally incorporating different oxygen spaces and different skies. Another interesting element is that this could be taken for a normal, commercially-produced panel.

** Regarding this specificity, did you notice any difference in the way London audience engaged with works as opposed to the way people in Bari have with previous exhibitions?

FB: No, actually. I didn’t notice any major difference, but the main difference was that English people were more able than other nationalities that came to the opening to recognise these images. So, for me, it was a success because the use of George Michael is a way of putting an element, or an image, between myself and the audience to stimulate a pleasant conversation.

** To speak about some of the broader themes in your practice, your work often addresses the hyper-circulation of capital, hyper-circulation of imagery, but at this moment in history, we’re seeing a crackdown on the free movement of people and the determination to re-erect borders. In using mass-produced images, are you attempting to touch on these political dimensions?

FB: Yes, sure this political dimension is totally present in my programme, but also in terms of my personal works. Also, one of the most exciting details of this show that — it wasn’t planned, it came spontaneously, but it was also a chance to proclaim the necessity of reflecting on specific issues like immigration, which is really strong at the moment — but three artists from this show are of African background, Olu, Atiena, and Kareem Lofty. I’m actually the only white person involved. For me, I don’t think in terms of these categories, but it came up. One of the artists realized this and she expressed her happiness to be in a show weighted in this way. So taking this element as a chance to confirm the necessity and importance of being collaborative, of being open, and not negating the access to anyone.**

The Il Cielo a Calci (intro) group exhibition was on at London’s Jupiter Woods, March 24, 2017.

share news item