The intimacies of the work in Sadness of Microtonality 3.3 talk of environment and experience. Nicolas Humbert’s final instalment of a trilogy work of exhibitions and performances, running at Berlin’s M.I/mi1glissé from April 6 to 8, feels like a sincere decision to soften the positions of audience/viewer and artist/performer across his varying fields of production.

An hour or so before the scheduled concert —opening a two-day exhibition to follow —a few people are sat on benches outside. The building’s facade maintains a resilience amid the commercial galleries and cafe-restaurants in the city’s Mitte district. It houses a large artist community throughout the floors above and a re-purposed theatre in the back.

Humbert is in the space setting up. In the window looking out over the doorway is a drawing of the Egyptian God, Set. On close inspection its surface is covered in burn marks and residue from a soldering iron. On the other side of the room is a white bar or counter, pushed up against a wall, a group of Humbert’s works collectively titled ‘Endfile’ convene around it. An LCD monitor sits on top along with two collages in A4 plastic wallets, on the wall a further arrangement hangs in plastic packaging alongside three drawings.

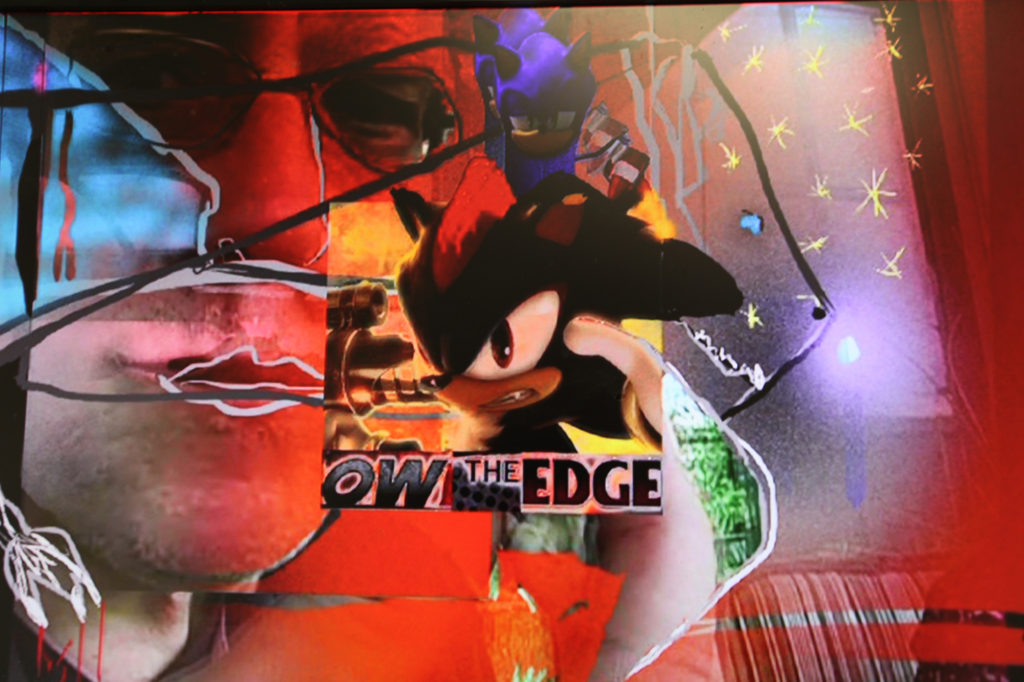

The monitor shows a static, semi-transparent digital composition in front of a YouTube clip of a man filming himself eating a sausage in his home: An instructional, tongue-in-cheek demonstration on how to eat a traditional Weisswurst. At this stage the work feels like a Start Menu for a game and on the floor there is a PlayStation 3 playing the file, tucked beside the counter, which adds to this narrative.

A still of the man’s face burns at me through the pixels. My eyes trace a line drawing of a wolf across the screen and it floats amongst other symbols and logos that I can’t decipher. In the middle of the screen there is a cropped image of ‘90s video game avatar Sonic the Hedgehog with a text that reads “OW THE EDGE”. The text pokes fun at the clip’s content, trolling its simplicity and its lack of edginess. Sonic is shown here in black and red, a revamped character from a more recent version of the game in an attempt to give the hedgehog a new life for a new generation of players.

There is no information to accompany Sadness of Microtonality 3.3, and this coupled with the amount of material in the videos and collages accelerates their rawness. One of the drawings has a note on the counter beside it with a name written in pencil. I ask Humbert what this means. The drawing was made by the artist’s friend as they sat in a cafe together waiting for a filming job to start. Another drawing records observations of a train journey. The lack of information in the space encourages me to talk with Humbert and curator Joel Mu. Access to the work feels deregulated in this way like much of the M.I/mi1glissé programming and does so with its community in mind. Several works contain lines of written code scrawled in pen and pencil. Ancient and futuristic, the specific framework of the coding language is redirected through its new materials into mark-making and symbolism.

In the center of the room two mattresses have been brought down from the living space upstairs to prepare a stage for the 9pm event. Billed as a concert online and not a performance, this wording feels like a subtle interrogation of its context. Sat at the edge of the mattress island, a Nintendo 3DS in a papier-mâché crown displays a video that documents neuesternenkunde.neocities.org one of Humbert’s websites. Filmed using a 3D camera, the video scans the surface of a screen, attempting to focus on and move between elements trying to find three-dimensional depth. What we see being played back is a messy register of the website and its architecture. This video feels really important to the way Humbert presents us with his practice. It effects a technological disuse and our access is directed through the console and its consumer-3D aspirations. The viewer gets entangled between a process of capturing the material and experiencing it.

The concert, a work entitled ‘Denmark Siren’ begins its drone through a pair of computer speakers. Projected on the wall behind, Humbert’s laptop screen shows the program Supercollider, its lines of code have been altered into a familiar/generic gothic font. I close my eyes and focus my ears. Some coins fall to the floor and a small dog wanders around. The volume is subtle and the room’s sounds fold into the composition. Twenty minutes in, Humbert abruptly halts the program and freestyles a pack of irregular clicks and whimpers using only his vocal chords. After a minute or so he returns to the laptop and re-engages the planned material, and after some time, a human voice emerges in the mix. It is a fuzzy repetitive shouting, someone in the audience acknowledges the sample, a possible field recording they collaborated on, or perhaps it is their voice?

After the concert I ask Humbert about the vocal break. He said that the dog in the audience influenced him, and that he is able to replicate subtle animal sounds. He also tells me that the font is the same generic typeface used by notorious black metal band Burzum for their albums. Already codified and specific in its language, the algorithmic composition gets pushed behind a further layer of signification here, unleashing a darker reading to those who may be able to access it. The standard gothic typeface was used by Burzum as a non-aesthetic decision to not have a logo or a constructed brand identity but these things aggregate historically and get referred to specifically within sub-cultures. It feels like a humorous take on a traditional form of branding, like writing in marker pen a band’s name on your backpack, and the sadness in what is co-opted and what is lost in these gestures.

Sat before the humble stage-set, I begin to think about sadness. Is Humbert trying to produce a different space for us to experience it? It’s immersive possibilities are pared down through a quasi-domestic arrangement that feels pragmatic, but what is to become of the concert artefacts that remain as an exhibition? They become sad sculptures, scraps of experience that have been used already. What is the realm of my experience as someone non-native to his codes and symbols? What do I experience if I didn’t make it to the concert? Humbert’s position is open and both his work and the context challenge his subcultures their specificity and what it is we can experience depending on what our access is.**