The number of photos in the digital world, especially in the social media sector, can be overwhelming. Whether moving around in these spaces yourself or occasionally peeking the screens of other passengers on public transport, there is an endless sequence of generic images to be caught at any given time. Another historically-nourished view of these sequences places them in a tradition of ‘amateur photography’, where their inherent perspective often fulfils socio-political functions. In a historical review, however, the question arises as to what position digital photos can assume in history, or whether these pictures of the everyday can even be subjected to a new interrogation.

The Amateur Photography. From Bauhaus to Instagram survey exhibition, which ran at Hamburg’s Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe from October 3, 2019, to January 12, 2020, builds a bridge between the first photographic experiments at the Bauhaus to today’s forms of image-making on digital platforms. Attempts to order the material, which has already been pre-sorted by private or institutional collections, state archives or online databases, become clear as central endeavours the show undertakes. In one large room, the exhibition thus arranges an overwhelming amount of photos, albums, journals and excerpts from these platforms in grey supermarket shelves, which superimpose an impression of the everyday on the pictures and thus question their relationship to them. The shelves are set upon a deep blue carpet that evokes colors used in social media. The heterogeneity of contexts then also raises the question of the changing function of amateur photography in society.

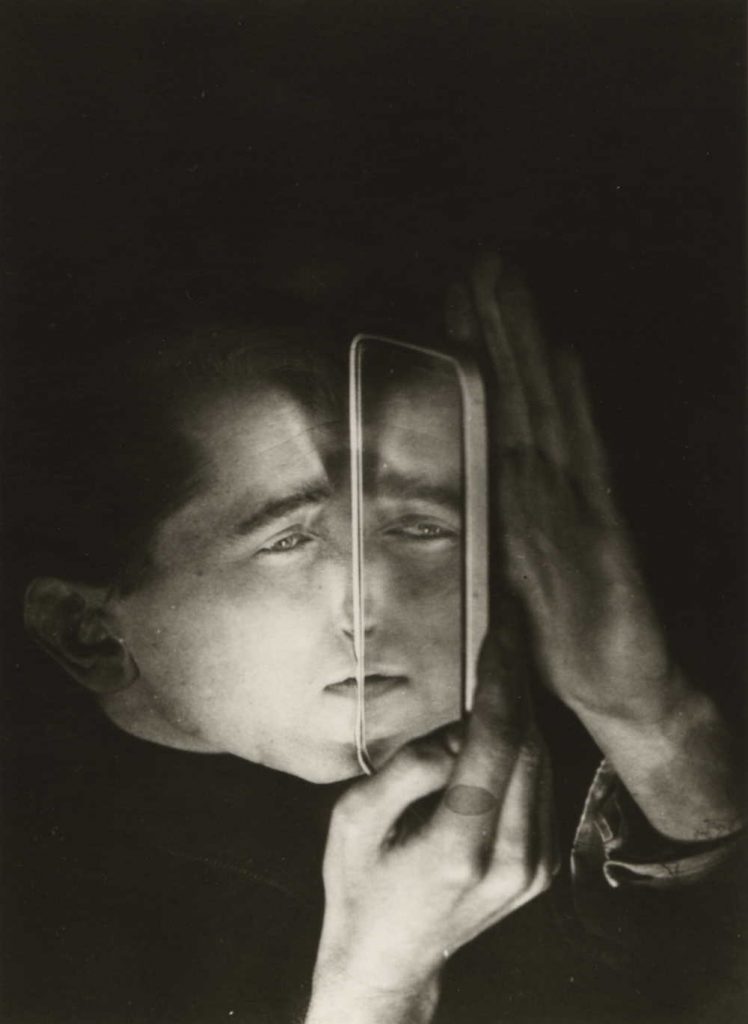

A focus on an early aesthetic form of what is summarised under the term ‘amateur photography’ forms the prelude and introduces a preliminary tension: Iconic experiments of Bauhaus students in exposure, perspective and sharpness—like the ones by Lotte Beese—are taken up and turned around. It reverses the common advice for amateur photographers of illustrated perspectives on objects being deemed unnatural or labelling motion blur as mistake. This marks an ongoing dialectic between the aesthetic and social function of photography and positions the amateur herself within a field of newly overlapping social roles. The first so-called photo amateurs and also advisory magazines appeared at the turn of the 20th century with the spread of portable cameras. It’s also the starting point for a tendency towards democratization in photographic practice, which Amateur Photography. From Bauhaus to Instagram analyses throughout.

Democratization concerned not only the growing range of inexpensive cameras—what can be compared to the explosion of digital photos through smartphone cameras—but also their use as a political instrument of the labour movement. There is ample evidence of this through a range of photographic magazines that were media tools for the emancipation of the working class in Germany in the 1920s and 1970s. The central part of the exhibition is a display of various issues and single-framed sheets of magazines, such as Der Arbeiterfotograf—the official organ of Association of Workers – Photographers of Germany (VdAFD)—or Arbeiterfotografie. Both aimed at documenting labour by workers themselves, thus illustrating the importance of the perspective behind the camera.

Originated in Germany in the 1920s and integrated into the labour movement, working-class photography became a social documentary practice close to the trade unions. Its own documentation of everyday life—and thus often also of suffering—was explicitly opposed to a bourgeois perspective ascribed to reporters. Therefore the photography seen here very much challenged assumed roles within society and can be placed in a historical tradition—as described by Rancière in Nights of Labour—that looks at the figure of the worker artist in 19th-century France. The shelf formations fulfil their function most clearly here, transforming the space into an archive that, in addition to prints of individual photos, holds folders and collections of magazines. These provide insight into an everyday working life that was structured by its repetitive activities. In a 1975 issue of Arbeiterfotografie, there is a series marking the ‘Year of the Woman’, for which Oskar Krause was commissioned to document his wife’s everyday life photographically. Under the generic title ‘A worker photographs his wife’, the images explore the usual life situation of a working-class couple pointing at the situation of women from a male perspective. The magazine commissioned Monika Krause’s husband to record her at work as a saleswoman in the supermarket, at trade union meetings, as well as in her daily housework and childcare routine. Through the juxtaposition of the snapshot-like photos of these two jobs, Krause highlights her work as a ‘double burden’. The photographic practice also reveals a hesitant self-awareness, as he describes in an accompanying text, ‘When I had taken this picture and saw the photos, one says to oneself: That a woman can manage so much!’

The thematization of the importance of the perspective behind the photographs, as well as their audiences continues nearby, where the private archive of a West German family from Düsseldorf shows solidarity with the anti-nuclear movement. The grey folders gather glossy colour photos of protests, from around the radioactive waster transport in Gorleben in the mid-90s. Followed by the picture series is a handwritten letter under the warning title ‘Attention (all)!’. The text addresses the potential viewer of the album. For them, it is clear that a media public was equated with state control, whereas their private sphere is positioned as political resistance. The function of a collection, as well as its audience that is only hinted at here, is found in the trace of the letter as an instruction. This also refers to the ambivalences that a contemporary exhibition and reception of these initially private photographs still brings with it, positioning them in contrast to pictures on public digital platforms.

On the other side of the worker photos are printed screenshots of differently-frequented Instagram accounts, such as julian_inic, who shows himself standing around with a dog, or in front of art. This is initially a harsh break within the exhibition, which evokes the question of the exact connection between the two. The framed extracts taken from accounts fascinates, perhaps because it is strange to see screenshots in a museum exhibition of what one might otherwise see on one’s own smartphone display. In addition, similar motifs are repeated as an experiment in another form, as a slideshow on a screen: A cooperation project with schools in Hamburg where pupils make their mobile phone photos, or a selection of them available to the exhibition. Teenagers follow the cliché of seemingly randomly photographing everything in their environment, but predominantly themselves. Both these ‘works’ in the exhibition primarily draw attention to the production of a large number of images, of which we only ever see small sections. At the same time, questions arise as to the reception of the pictures and their actual addressees, as well as a feeling of foreignness towards the photos. The fact that a sociopolitical, or even aesthetic location of the photos is not so easily applicable certainly also plays a role here.

Elsewhere, one can find an analogue photo series from the 80s and 90s, suggesting a section of a much larger collection. The pictures, in a glossy 9×13 cm format, shows the same 20-something woman in different poses and situations. She’s in the kitchen or in front of a stack of boxes, but always in new trendy outfits. The person is unidentified and it’s unclear whether these are self-portraits or not. The pictures are arranged under the title, ‘Woman Displaying Various Outfits’ and are part of Neu-Ulm’s Walther Collection. Because of their essential anonymity and privateness (like a lot of amateur photography) they are ambivalent objects in public collections. They direct the focus once again onto their function, which—in addition to aesthetic moments—arises here even more through the repetition of their motif: In today’s nostalgia, they illustrate a particular fragility in the attempt to stage a self through portraits, thus establishing a connection to contemporary digital photographic practices.

According to social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson, photo sharing platforms promise your images will be seen but they also fulfil a social function. In his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media, Jurgenson argues for understanding digitally-shared photos as a form of language that is constantly expanding via shared pictorial symbols, such as emojis and memes. According to his hypothesis, the charge that too many banal photos are in circulation implies that these images are subject to an aesthetic evaluation, a perspective that is not relevant to social photos, since they fulfil a social rather than an aesthetic function. This tension runs central throughout the exhibition, as becomes clear at the Bauhaus section opening the show, but also in the workers’ photographs, which were opposed to a bourgeois aesthetic.

The fact that the ways of a different institutionalisation must be applied to each photograph, becomes particularly clear in a black box in the middle of the exhibition space. Here, two private slide series face each other: On the one hand, there are the private photographs of Axel Herrmann, a West German pilot who—together with his stewardess wife—recorded joint journeys around the world in the 1970s on 35mm slide film. In the course of their son Daniel’s studies at the HfG Offenbach, these images were digitised and turned into the artistic work ‘Continental Breakfast’. Slightly faded, it shows the generic holiday motifs of the upper middle class, as endless pictures of airplanes, pools, hotels and beaches. On the other side, running in the same rhythm, one sees even more faded travel pictures of the East German teacher Hildegard Schneider, who also recorded her travels, in her case to socialist countries. As stated on a label outside, these 35mm slides were shown by her in school lessons with the idea of representing solidarity among socialist nations. This photo series is now kept in the public documentation centre of everyday culture of the GDR in Eisenhüttenstadt: showing portraits, switchboards that give us no clue about their location, a missile memorial in Moscow and high-voltage systems. But it is not only the differences in motifs that come to the fore in this juxtaposition, but also their changing function—between a private collection, art or historical documents in the archive of a bygone era.

These tensions and dialectic movements within the genre of amateur photography are made explicit in the exhibition, drawing attention to the differences that affect the respective histories of the photographs in their time. Depending on their order and context, they fulfilled different functions, as aesthetic or political objects, or ultimately as historical documents. The spatial arrangement of the images in Amateur Photography. From Bauhaus to Instagram creates an impression of superficial similarities, behind which a history of differences opens up. Within that set-up, there is a sense of disorder regarding the position of digital photos, which ultimately confronts us with our own expectations towards their assumed function within society. As in the exhibition’s historical retrospective, it is guided by implicit aesthetic or political evaluations. In contrast to this, however, the most fascinating examples of amateur photography become evident as social practice and means of communication, to which we as visitors of an exhibition are not necessarily the intended counterpart. Thus, the exhibition perhaps unintentionally draws attention to the resistance that disorder implies.**