My interview with Juliana Huxtable didn’t go great the first time. Speaking over the phone in Lisbon, while waiting for her boyfriend at the airport, the conversation with the Texas-born artist was stilted, and I was failing. “It’s hard for me to manoeuvre if I don’t feel like I’m in the flow of the conversation,” she tells me from her base in Berlin a few days later, having graciously agreed to a do over. “I don’t mean to be stressful. If it’s something that I’ve been asked a lot it can make me lose interest, but I totally sympathize because I also do interviews with artists.”

Among many other things, Huxtable is also a writer. Her broad reaching interdisciplinary practice includes elements of poetry, performance and visual art, DJing, fashion and events but she’s been writing since childhood and thought that’s what she’d do after college. “That’s what I was assuming I was going to be before my art took off,” she says the second time we talk for a far longer, easier and more enlightening chat, breathlessly covering the gamut of socio-political subjects—including, race, gender and sexuality—Huxtable is known for engaging. “I’m starting to get back into it because I realized that I enjoyed it and miss it a bit.”

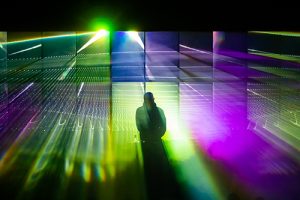

After moving to New York, Huxtable famously gained attention for her Tumblr, while working as a legal assistant at the ACLU, joining ballroom-inspired collective House of Ladosha and throwing her own genderqueer club night, Shock Value in the 2010s. Even now, the reason for this conversation is to promote her upcoming Break Off party, organised with producer Ziúr at Berlin’s Traumabarundkino on February 29, but Huxtable is just as keen on talking about college debate team and a formative fifth grade writing club: “From that point, I wrote poetry obsessively. I did write poetry before then but I really took that on as an identity.”

It’s with this in mind that it seems almost perverse to write about and reinterpret the work of someone who already has such a strong grasp on language. As the author behind 2017’s collection of texts Mucus in My Pineal Gland and a novella called Life co-written with another artist-writer Hannah Black, Huxtable has her own space to say exactly what she means, unfiltered by the point of view of another person. I had considered making this interview a prose piece to try to cover all bases—the relationship between trauma and identity, the ideology of representation and a childhood friend called Caitlin whose parents were formative queer figures in Huxtable’s life. But the artist is so effortlessly eloquent that it made sense to allow her own words to speak for themselves.

**You had a hard time growing up, right? I’ve often wondered, is creativity a thing that you’re born with or is it a coping mechanism?

Juliana Huxtable: My inclination is to probably say is can be either or and is probably a combination of both in most instances. It’s like gender, I don’t think that you can reduce it to whatever that innateness is. That would be a form of essentialism and determinism that I generally find myself at odds with.

I was always very artistic, so I think there is something innate there but I don’t know if it was a coping mechanism, as much as it was just a way to express what I was navigating. To ‘cope’ with something implies to wrestle with it, or acknowledge it, or work through it, and I don’t know if that was necessarily what was happening. That seems like almost a psychological question that I would be unable to answer.

It wasn’t so clear to me at the time but that all the things that I was struggling with were coming out. I dealt with a lot of physical abuse as a child. I dealt with a lot of verbal abuse. We didn’t have the name for these things at the time, but I had a mother who was struggling with bipolar and schizophrenia, with a tendency towards episodes depending on what triggered her. [I was] dealing with that as a child, on top of being intersex and having a kind of gender indeterminate body, before I even got to choose an indeterminate gender identity.

Most people assume when it comes to narratives of quote-unquote ‘trans people’—which is a very large umbrella—that somatically your body existed somewhat comfortably within the spectrum of what people would identify as male or female, and then you transition to female or male, respectively. But I already dealt with a sense of bodily ambiguity, or in-between-ness, or beyond binary-ness.

**Do you think trans as a label can be reductive?

JH: Of course, it can. I think it’s useful when it’s useful and it’s not when it’s not. I’m generally an advocate for broader terms, and identification, and recognition, when it’s useful and when it activates something, and when it recognizes a spectrum of being. But then the identity category establishes its own fetishes that then people are attracted to for the purpose of monetizing, exploiting it for certain forms of sympathy, marketing, self-aggrandizement via a kind of attention economy. I think that identity can be wrapped up in a lot of those things but I also don’t want to say that it’s useless because I definitely don’t believe that. I’m also not a fan of this reactionary, complete anti-identity politics, where we return to some kind of weird idea that by totally rejecting identity discourse, we return to a bare humanist meritocracy or something like that. I really don’t buy that.

I think oftentimes trans-ness as a concept is reductive—it’s very loaded with cultural capital right now, at least in terms of marketing and a larger kind of ideology of representation via visibility and things like that. I find myself actually sometimes almost bored by how much I talk about visibility economies but we’re just in the moment, so it feels prescient.

**I’m interested in what you have to say about monetizing and marketing identity because I’ve often thought about the refusal of labels. As a successful artist in your own right, you appear to problematise this categorisation, both personally, politically and professionally through your interdisciplinary practice, while still maintaining visibility and a voice.

JH: As a person who happens to inhabit a lot of spaces that are easily marketed under certain labels—black, trans, intersex, queer, woman—there are a lot of categories that most people would say that it’s very easy to tie me to those labels, and to the worlds that those labels like activate. But when it comes to this ‘marketability of visibility’, and also visibility as ostensibly a mode of political engagement, I experienced the period of time before that, at least before it was so explicit.

When I moved to New York and really shifted my identification from more genderqueer, non-binary, femme, into taking on the language and identifying as a trans woman, when that happened there were no young trans girls at the rave, young trans girls at the poetry festival. I experienced that as a phenomenon that was new to me—my ascension, my early adulthood really happened before that. Then I witnessed that grow so it’s been interesting for me because I found myself very early on really receiving a lot of attention for that without necessarily understanding what was happening.

**You used to do more fashion, what’s your relationship to it now?

JH: What’s funny is that early on I used to do a lot of campaigns and none of them, none of them were ever framed around transness. It was more, they wanted cool, young, New York people to represent kind of left-of-centre brands. It was really nice because I felt like I was building something that was specific to just me and the universe that I was creating. I don’t do campaigns anymore because I refuse to do something that’s marketed as, ‘look how progressive we are because we’ve hired Juliana’.

Also, I’ve never once believed that being in a fashion campaign is liberating someone or is changing economic factors of exploitation that people are experiencing in their material lives. I don’t think that there’s a direct relationship at all between these already highly visible culture industry, gender-nonconforming, black people. I’d rather see a fashion campaign that’s diverse rather than not diverse but that’s not the same thing as rolling back regulations. That’s not the same thing as creating jobs-based protections for people so that they don’t end up having to do extreme forms of survival labour. That doesn’t do any of those things.

There’s an assumption that if we push marginalized categories of people into the visible fore, that’s political. I think about the lazy, out of context use of Audre Lorde quotes, where it’s like, ‘self-care is a radical act’ and all of a sudden, it’s a fashion campaign with me getting my nails done.

**It’s also strange to reposition the fashion industry in this way because, as a space, it’s always been quite gender fluid.

JH: I don’t know that the fashion industry has a consistent and/or necessarily amplifying relationship with gender variance. I think it goes in and out of fashion, just like everything goes in and out of fashion. Fashion is very cyclical. Things leave, things return and then there’s the introduction, or reintroduction of certain cultural signs in order to create the illusion of constant movement. It’s notorious for directors, fashion houses and these designers that are under insane duress trying to produce because fashion is obsessive in its desire to both consume and represent what culture is or is not. At least in terms of what it heralds as ‘revolutionary’, I would say it privileges gender variance but within a kind of male-identified spectrum.

You have a long history of the ‘dandy’ or the ‘young nymph’, but it either amplifies femininity as a form that’s directly tied to notions of womanhood or amplifies femininity as a deviation from maleness. We are in this cycle where female masculinity is also being given creative space—that’s definitely not something you see a lot of historically. Maybe you could say that gender variance has been valued but total gender transgression has not necessarily been valued. There’s a long history of trans women basically being quiet or hiding their identity in order to function in fashion because, generally-speaking, you’re in a highly dimorphic, cis-gendered world.

**Speaking of these cycles, I guess that’s where the danger is in investing too much in the emancipatory potential of fashion.

JH: Right. I think a lot of the purpose of this construct of the cyclical nature, or the constantly changing nature of fashion is to maintain an industry. It’s to maintain a sense of temporal novelty so that consumers always feel like they’re getting something new. Ultimately, it’s a way of sustaining industry, and it’s an industry that’s fascinating to me because previously there was arguably a lot of distance between how the fashion industry works and how, let’s say, politics, presidential politics or something like that works but I think those things are becoming increasingly more indistinguishable.

**I think you’re right about that. You’re also in an interesting position because you work across these fields, as well as within art and writing. Is there something subversive about the way you engage with fashion as a form?

JH: When I say fashion, I’m generally referring both to the fashion industry and to the kind of larger cultural and social fields of ornamentation and self-styling, et cetera, that is fashion in practice. I really like fashion and I think that, despite my criticisms of the industry itself, I think that it’s a space in which a lot is being done. It’s a sphere that has unfortunately—within critical, analytical and even academic-adjacent, arguably literary, fields—received the brunt of sexism and homophobia. I think that fashion is assumed to be superfluous; it’s assumed to be immediate; it’s assumed to be not long lasting. I think those critiques that one might lodge with the fashion industry become opportunities to dismiss these larger fields of meaning, and signification, and practice, and play, and gender, and race.

I always crave that one might be able to engage fashion seriously, which isn’t to say without fun or something like that but seriously in the sense that it is worthy of a kind of critical and analytical framework. We can learn, and read, and glean things about the world that we wouldn’t if we weren’t paying attention to fashion.

**I can relate to this impulse of being highly critical of a field, practice or industry that you both work in and love. The assumption is that you hate it because you’re critical but it’s actually the opposite.

JH: I’m just a critical person generally speaking but I see critical engagement as generative. That’s also maybe not the most popular take right now. There are increasing schools of thought that are gaining a lot of traction, you could even call it an ideological shift in which people are taking the response to the years, and years, and years of critical theory, and intersectionality, and feminist theory, and queer theory, as all essentially critical forms of straitjackets that have led us to a position in which we now have no real positive identification. It’s like a solipsistic, agency-limiting way to overplay the nature of identity and the historical harms attached to certain identities. I think we’re experiencing a kind of backlash against that, in a lot of ways.

I really disagree with that position and sometimes even in literature you have a lot of people that just hate this new diaristic, first person perspective. Or poets who hate what’s seen as Tumblr or social media poetry because it doesn’t reach towards the ‘loftier’ questions, and ideals, and issues that poetry should be. Instead it turns into this like super self-centred practice of identity performance. While I get a lot of those criticisms, I’m very wary of that. I see critical engagement. I see being critical of the structures around us—even through a kind of identity discourse —as a way of making meaning in and of itself.**