“Generally, I don’t subscribe to the definition of feminist waves, because the use of those categories has largely come out of Anglo-American feminist discourse, whereas I situate myself primarily within the genealogy of Continental difference feminism” says Alex Martinis Roe over an email chat when I ask her about feminist movements/waves. She goes on to explain that “the way that those waves have been defined entails a progress narrative, brought about by an unfortunate repetition of the Electra complex.”

The Berlin-based artist, who is currently showing new film installation To Become Two at London’s The Showroom running April 26 to June 10, is more concerned with conversational entanglement and a discourse of becoming rather than “the destructive and inaccurate effects of generalisation” that separates generations.

The installation will include six films that focus on what the press release defines as “international feminist communities and their political practices” across Europe and Australia. Through observing, archiving and engaging in oral interviews, Martinis Roe looks at histories to understand and engage in present collectivity. In addition to the films, there will be a number of events and workshops that will eventually culminate in a final project with the aim to “bridge different positions and political projects that nevertheless have compatible objectives.”

Expanding on her approach to research and and what excites her most about transgenerational feminism, Martinis Roe talks to us about documentary and authority, solidarity-in-difference and the power of story-telling as a way to access the past and present of feminist politics.

** “My hope is that the virtual futures that emerge through telling these histories become propositions for new collective practices.” Does engaging with the vast history of feminism make you more optimistic about the it’s futures, or more jaded?

Alex Martinis Roe: I’m less concerned with predicting the future than trying to do something toward bringing about one I want to live in. Feminist and other social movements concerned with the liberation of difference are the inspiration for that attitude, and certainly they have achieved a huge amount. On the other hand, I don’t think that the basic concerns of the feminist groups I have done research on are all that different from my own and those of my contemporaries, although there is a thirty-to- forty year difference in our generations. I think a lot of what is perceived as “progress” is not so simple. For example, in countries with a long history of feminism, more women now participate in once completely male-dominated industries, but then the competitive, capitalist structure of those industries has not changed in equal measure to accommodate the necessarily changing structures of families and the division of care labour, leading to enormous pressure on women to overwork and hide their family commitments. What I find most inspiring about feminism is its transgenerational character. The fact that it is an evolving culture, language and system of values with a lengthening history that exists within and also beside other cultures. Judging from my experience of the level of excitement that it generates among those who take part in it, I can say that I feel very optimistic about the future of this minor culture.

** What does engaging with the past and imagined futures of feminism tell you about the present?

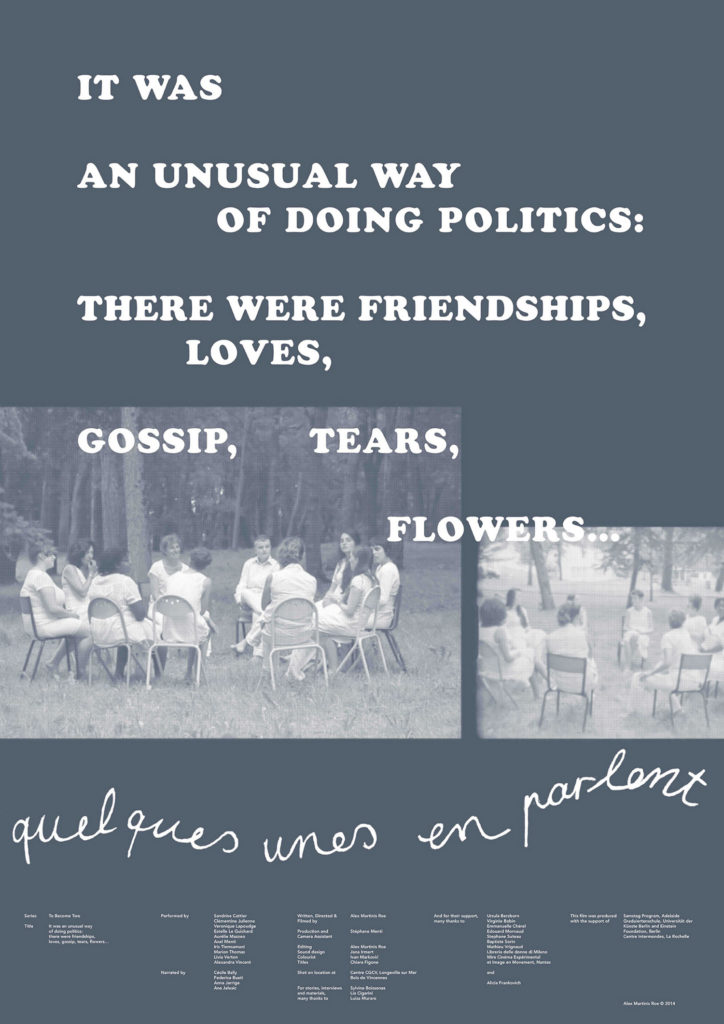

AMR: The most important practice for productive relations among different generations, in my experience, is acknowledgement. One doesn’t have to be dutiful, but to be dutifully undutiful, like the way that Rosi Braidotti has approached feminist genealogies. This entails situating yourself in relation to those who came before, but also affirming, continuing and doing the politics of difference they invented – not doing and being the same as them. I’m thinking here in particular of Luce Irigaray’s legacy: the feminine can only come to define itself differently through a genealogy of women. One of the key generational rivalries in Anglo-American contexts has been between movement and academic feminism. That rift comes from forgetting that the political project of entering institutions of knowledge and power and changing them from within was an endeavour begun by the women’s liberation movements, and has necessarily required “speaking the language.” Seeking to redress the perceived disjunction between these two “waves/movements” has been a key focus in my project To Become Two (2014-2017), which as a social history of ideas and practices, shows how key academic feminist methods and concepts (that can trace their genealogy to sexual difference feminism) were generated in and elaborated from the relational practices of the women’s liberation movements.

** In your films, how much do you intervene to create your own narrative? Or do you keep it as documentary as possible?

AMR: Documentaries never present an unmediated view onto past events and ideas – they are always moulded to a narrative. My Two Become Two film series is a kind of essay on the voice-over and other key documentary structures, exploring the way they produce authority while attempting to do that differently. I think narratives should always be situated by clear framing with regard to the position, discourse and investment of the author/s in the topic. To Become Two is in that way inherently autobiographical. It is a social history of the genealogy of “feminist new materialism” / posthumanism to sexual difference feminism, but it is as situated as the genealogy of my own feminist formation – the ideas, books, and people who have shaped my knowledge and methods. It is in that sense a partial history, but as I said, I don’t think there is any other kind, the difference is that I have used feminist historiographical methods that foreground that. I used a number of methods to do the research to generate this history of the relations among these related feminist groups and communities including archival research, oral history interviewing and participant observation. Using participant observation (which involves becoming a part of the community you are researching) as a way of learning about the past was a kind of quantum experience of time, because I was living and experiencing the past in the here and now insofar that it was the way I came to understand the concepts and practices that I had previously considered “history”.

I now understand history as an activity of making particular virtualities in the past actual. This performative appreciation of history was then further lived out in the practices of narration that I developed with women from my own generation. Telling these stories together and exploring their potential legacy in our own lives became a way of doing feminist politics here and now.

** In relation to cross-generational and multidirectional voices in different communities, and in the context of ’intersectional feminism’ , is there something unifying going on here that you’re attracted to, or rather something more complex and dividing?

AMR: I would say neither. Certainly solidarity and collaboration are extremely important, but unity implies the abolition of difference and the forming of one voice together, which I think is impossible. The reduction of differences to one voice for the sake of political efficiency will be self-defeating, because in that scheme, dominant subject positions will continue to prevail over minor ones. That’s why I’m not interested in horizontal models of collective politics, like consensus, because power becomes insidious when it is not acknowledged. It needs to be worked on explicitly through the political model itself. I don’t think that it is difference that creates division. It is precisely the demand, expectation and movement toward sameness that creates division, because it excludes difference. Difference has been systematically excluded in Western cultures, which is why it might be mistaken for being the cause of divisions. But consider intimacy – the love between child and parent and between lovers and close friends is a love for another’s uniqueness, what is irreplaceable, unrepeatable about them – their difference. That difference is inherently relational and I am committed, along with my comrades, to generating cultural value for that difference of each of us, between us, as the fabric of strong communities.

** Is the project going to continue throughout your practice?

AMR: A politics of difference as I have just described will definitely continue throughout my practice, and the networks that have been generated through the To Become Two project have their own life, which exceeds any project of mine, and which I will continue to be committed to. The central question I want to address now is: at this moment when fascism is on the rise, what are some key techniques that will generate solidarity and collaboration amongst activist groupings that have different foci, but are nevertheless compatible in their broadest non-fascist objectives? My wager is that there are useful strategies and knowledge to be gained from an analysis of minor histories of solidarity-in- difference, which can form the basis for developing a toolbox for practices of alliance now.**