One weekend only. From April 8 until April 9, an ex-industrial warehouse in England’s Truro is transformed into an immersive installation that includes film, painting, sculpture, print, posters, quilt-making as well as live music and a DJ set. The ambitious project Unstable Monuments, curated by Matthew Benington and produced by Jesse Leroy Smith and Sam Bassett, brings together fourteen artists from England, Germany and Denmark. Looking at the monument through the lens of faith, gender, architecture, anthropology, family and ritual, the works converse in a shared disenchantment, moving away from what Benington calls “an inflexible state of mind.”

What’s refreshing about the show is the positive energy behind its critique; rather than fixating on the ruin as a space to sympathize, mourn or retaliate against, loss is seen as potential for re-evaluating the structure of our faith, icons and ancestry. The exhibition acts as a breeding ground in favour of decay and acknowledges the necessity for new life to grow into a more malleable and undefinable space. Truro, an ex-industrial mining town in the ceremonial county of Cornwall, felt a fitting location for the show: in-flux and filled with defunct buildings that no longer serve the same purpose that they were built for.

The enormous venue is currently an industrial bakery between disintegration and renewal, housing an impressive amount of work by the large community of people involved. The unpolished vibes provide an appropriate backdrop, especially for Dick Jewell‘s film compiling over 40 years of his own footage from UK raves. A mix of his previous films ‘Rave + Breaks’ (1992), ‘Skins’ (1978) and ‘The Jazz Room’ (1987) are among some of the archive presented. We watch as bodies move through time periods and the ecstatic display of religious experience remains a constant. Devoid of the same euphoria, the religious experience is contrasted and deconstructed in Kathryn Ferguson’s film ‘Máthair’ (2016). Irish for mother, the large projection constructs a personal vision of homeland by piecing together fragments of patterned behaviour, memories and thoughts that revisit recycled rituals. In costume, the artist forces herself into a hyperreal landscape, embodying the ghosts of the past that live through her in the present. It’s inspired by a holy pilgrimage she took with her own mother, the female is weaved through layers of history into a new, personal narrative.

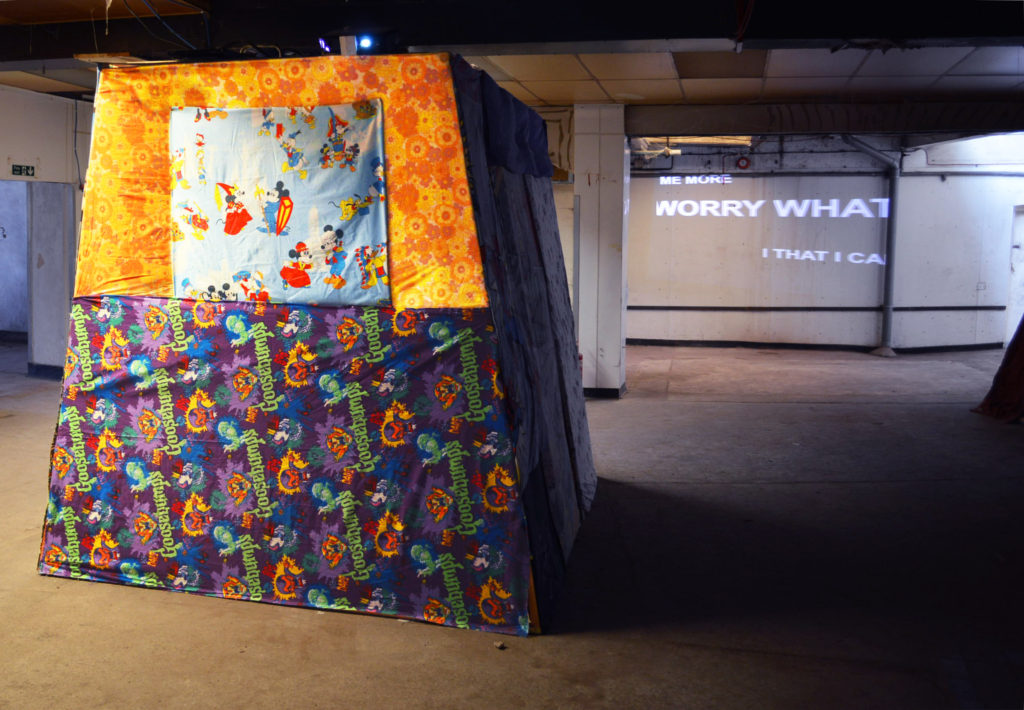

Similarly, co-curator Benington’s ‘Hide’ series, which began in 2013 and continually re-births in new locations, calls attention to missing monuments and acts as a dedication to forgotten and displaced narratives. The exterior is made of children’s bedsheets, and its haphazard shape looks like a fort or den; a safe space carved out by childhood imagination. Twenty-five meters of etched steel plates support its precarious structure. Made from family and found photographs, the diverse content all deals with subjects displaced from their homes. The little room was packed with bodies on the evening of the opening, while Bennington revealed some of the backstories behind the images. Somewhere between a studio, an artwork and a place of safety, the experience felt like a proposal for an intimate dialogue.

The theme of support and safety is prevalent throughout many of the works, especially in particular Leon Matis Robin Monies‘ ‘Comforts’ (2016) series of quilts made by hand-sewing garments, props and other symbolic objects once used to define one’s rank or status within a particular society of people. Mixing up the reference points of community and hierarchy, their only purpose is to keep the owner warm. Marianne Keating‘s text project ‘Tell Me’ (2016) gives the public a place to house their darkest secrets where they were asked to anonymously respond to postcards placed in surgeries, cafes, pubs, libraries, etc. The private emotions were then displaced back into the public, and projected onto the facade of the building. Bernhard Holaschke‘s ‘Stealth and Days’ (2016) video interspersed his own confessional writing between images of appropriated historical footage, handheld shots inside the natural history museum and lo-fi Google images. The text between cuts, reads:

“i see myself and i am/ seized by disgust and fear/ through my indifference to people / I’ve been displaced/ out of their society/ now i live in a ghost world/ enclosed in my dreams and imaginings.”

What feels like a total rejection of the white-walled gallery and the stale professionalism that it requires, Unstable Monuments embraces a more spontaneous and honest approach to making. Harnessing the strength of ‘weak’ and ‘broken’, a camaraderie emerges that undermines the individualistic way we approach community, and questions why the dead have to be more alive in us than the living.**