“I’m going to need a bigger house!” A satisfied collector says this in front of a 12 foot high Georg Baselitz painting, loud enough for everyone in the room to hear. He is standing possessively next to the work in a suitcase-scrunched linen suit at the 56th Venice Biennale, running May 9 to November 22. Given that this year’s curator, Okwui Enwezor, has placed Das Kapital by Karl Marx as a “filter” through which the work should be read, the irony of this small observance is flatly obvious. Enwezor has avoided a descriptive theme, instead proposing the biennale be viewed as a “parliament of forms”, a landscape of conflicting viewpoints in democratic contention in one place at one time. But here in Venice, where socially progressive messaging meets big capital, there is a peculiar schizophrenic sense a visitor might experience, sandwiched between the microscopic soul searching of isolated works and the macroscopic market processes of the art world.

Much has been written about contemporary art operation within a broader biopolitical and neoliberal economic context. As sites of efficiently produced creativity, gentrification, networking, translation and disruption, contemporary art has grown to become an essential tool in what Hito Steyerl has called “a transition to post-democracy”. This broad investigation is the topic of e-flux Journal’s contribution to the curated exhibition, Supercommunity, a daily release of texts by artists, writers and thinkers which are circulated via email and also posted on a billboard within the Giardini. “I am the supercommunity, and you are only starting to recognize me,” the manifesto-like editorial statement claims before laying out a hypothesis for a swarm-based, supranational system of cultural organisation which efficiently translates affect and reorganises resources seemingly purely for the pleasure of it. In some ways this project feels like a better introduction than Enwezor’s curatorial statement for the Venice Biennale, given that the event is too big to submit to summary and whose organisation is so much more decentralised and non-linear than the image a central curator presents.

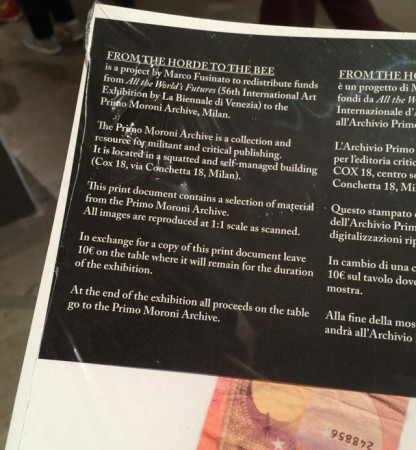

Having said this though, many works operate comfortably within the Das Kapital filter applied by Enwezor and work as deconstructions on ideas of exchange, value and labour. Most directly Isaac Julien’s two-channel video work ‘KAPITAL’ (2013) presents a public discussion between the artist and notable academic and lecturer on Marx, David Harvey. Marco Fusinato’s work ‘From the Horde to the Bee’ (2015) resulted from a residency in Milan with the Primo Moroni Archive of radical left-wing publishing. Fusinato places books containing scanned copies of resources from the archive around a large square table and, in exchange for ten euro thrown into the centre, visitors can take a copy away. Over the course of the biennale the pile of money, which is ultimately intended to end up donated to the archive, will grow, the stakes for its security slowly becoming higher. As such Fusinato plays out an experiment on the possibility of anarchism and grass roots self-organisation.

Walead Beshty’s sculptures are the result of a residency conducted in the Jalisco region in Mexico, which specialises economically in high-temperature fired ceramics. The clay sculptures are painted with reproductions of historic frescoes by José Clemente Orozco which depict the Spanish conquest of the Americas. In contrast, moving away from economic specialisation to artisanal production, Fatou Kandé Senghor’s documentary film ‘Giving Birth’ (2014) portrays the Senegalese ceramicist Seni Awa Camara sculpting a human form from clay inside her home. Hiwa K’s work ‘The Bell’ (2015) consists of a large church bell forged from recycled metal taken from salvaged weapons in Iraq, a process which reverses a repeating historical occurrence where cultural relics are melted down to produce artillery. In doing so he unpacks the international arms trade while presenting a silent icon for hope. Hito Steyerl’s video, entitled ‘Factory of the Sun’ (2015), consists of a science fiction narrative in the form of an unplayable video game which speculates on the coercion and measurement of immaterial labour within a “motion capture Gulag”.

Pamela Rosenkranz’s exhibition for the Swiss Pavilion called Our Product reframes the artwork as a scarcely existing commodity. Lighting effects, dispersed musk perfume and the softly playing synthetically generated sound of water operate on all senses at once often leaving the audience disoriented as to what they are experiencing. The effects are introduced so subtly that it is often difficult to tell whether what we are experiencing is a minor hallucination or real. Central to the exhibition is a bubbling fountain of generic “European skin tone” liquid, which casts the room with a reflective pink glow. This solution is concocted from a secret formula of trademarked ingredients used in the cosmetics industry, which are notable for the physical and psychological effects they promise the end user.

On the other hand, outside of the Central Pavilion and Arsenale, some exhibitions sit in stark contrast to Enwezor’s selection. Especially notable is the exhibition Slip of the Tongue which places a sizeable body of Danh Vo’s work alongside curated selections from the Pinault Collection. In welcome contrast to Enwezor’s curated show, this exhibition is generously spaced, which allows the viewer’s mind to meander obliquely through whimsically severe sculptural plays on demonic possession, Freudian slips, dismemberment and transformation. Works in this show subtly act upon each other to slowly reveal hidden meanings. For instance the lacerated plastic sheets of David Hammons’ ‘Untitled’ (2007) transforms to resemble flayed skin after it’s seen in association with Peter Hujar’s photograph ‘Andrew’s Back’ (1973) and Martin Wong’s painting ‘Inri’ (1984) not to mention countless other works featuring disembodied heads, genitals, lips and other body parts. The exhibition as a whole feels like a reader for Danh Vo’s mothertongue in the Danish Pavilion, providing an expansive set of visual reference points for a show whose meaning the artist seems to feel apprehensive about giving away too readily.

The biennale is also the natural place for countries to confront their pasts. The Belgium Pavilion takes its starting point from it’s troubling colonial history. Elisabetta Benassi’s work ‘M’FUMU’ (2015), whose title is taken from the name of a Congolese activist and intellectual of the early 20th century, consists of a Belgian tram stop constructed from casts of bones of exotic African animals sourced from the Royal Museum for Central Africa. Sammy Baloji’s series of photographs documents the historic 500 metre (the flight distance of a malarial mosquito) undeveloped sanitation zone between the city of Lubumbashi’s white and black neighbourhoods. Vincent Meessen presents a video installation ‘One, Two, Three’ (2015) which records his project to develop a new rendition of a near lost protest song written by Congolese Situationist Joseph M’Belolo in 1968. Together the exhibition serves as a series of actions against forgetting and an assertion of one of the central preoccupations of Meessen’s practice, that modernism occurred in dialogue with Africa and was not a purely European phenomenon.

In a similar vein, the Armenian Pavilion seeks to reconnect a global Armenian diaspora on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. The exhibition takes place inside the orthodox monastery on the island of San Lazzaro which itself actively collects relics and heritage objects relating to Armenian culture and identity. The artworks are installed among these efforts at reassemblage and as such the loaded site and the exhibition bleed together seamlessly in a way that no other venue in Venice manages to do. In the meticulous central courtyard garden, Rosana Palazyan has placed pressings of weeds on fabric embroidered with human hair. Beneath each image reads a text taken from a horticultural handbook such as “… has not yet been discovered a quality that has transformed them into a culture…”. Nina Katchadourian presents a series of video documentations of her and her parents’ efforts to learn to adopt one another’s accents, while Hera Büyüktaşçiyan sculptural works deal with the artist learning the Armenian alphabet as a child.

After leaving Venice the biennale begins to exist as an uncertain collection of memories where the order of works seen becomes muddied. My own imaginary exit-point is Sarah Sze’s installation ‘Landscape for an Event Suspended Indefinitely’ (2015). It would have been easy to walk past it and it is nice to think that it could be a quiet surprise accidently stumbled upon by an exhausted traveller weighed down by exhibition catalogues. Inside an overgrown, walled off garden at the very end of the Arsenale, the small sculptural interventions – fiddly assemblages of folded photographs, broken sticks, rocks, tape, string, clamps and candles – seem like attempts at busy work by a lonely last human trying to keep a sane mind. A garden tap drips slowly onto an installed bronze heap, ticking like a clock for a future era where time no longer matters. It’s easy to imagine that eventually the water would wear away the bronze monolith, the fragile works falling to the ground and decaying, in time becoming this rock here, that bush there. Amongst a densely compressed collision of attempts to deal with history and ‘all the world’s futures’ this garden felt like time softly reclaimed from human points of reference. With nothing left to bump into I lie down on the grass and overhear the old stones in the walls whispering, “Is this too big to fail?” **