The enigmatic Christopher Forgues (or C.F., as he’s also known) has been quietly and inscrutably publishing some of the strangest comics on the American underground scene for some time now, and Mere, a collection of self-produced comic zines released in 2012 and lovingly assembled by Picturebox, is sure to add to his growing reputation as one of the most unique comics artists working today. You may not like his work (and sometimes its sheer oddness can test the patience of even his biggest fans) but, once read, there is always something about the haunted, magical quality of his fevered imaginings and seemingly rudimentary doodles that keeps his work tantalising.

It’s this ability to keep the meaning of his work opaque, while still making a compelling strip that really defines C.F.’s comics. Even his more straightforward work, such as Powr Mastrs, the continuing story that really propelled him to the comic world’s attention, seems as if it’s been made according to the dictates of some magical ritual rather than to satisfy narrative logic. Characters mutate and transgress their physical boundaries constantly, and landscape and dialogue feel almost totemic, put in place to signify subconscious states rather than to represent any sense of place or particular motivation.

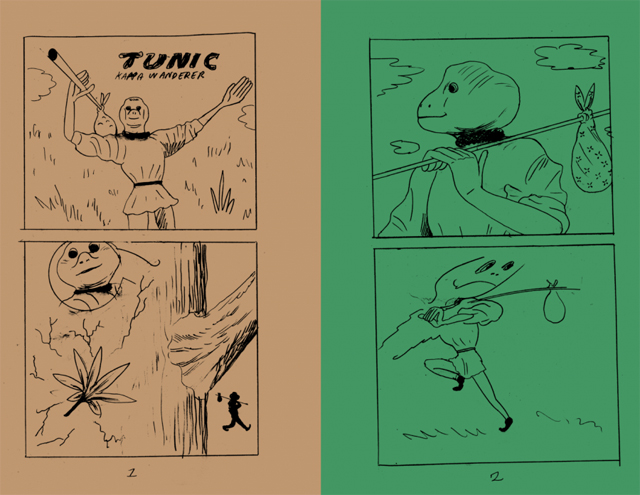

So, as you’d expect, when C.F. starts working with shorter strips the results are even looser. A series of crude doodles that on the face of it indicate nothing and say even less. But when collected together a weird sense of unity settles around them. And it becomes impossible not to see them as part of a greater whole, a whole that has more in common with a book of spells than with any other “graphic novel” that could be placed next to Mere on the racks.

A peculiar tongue-in-cheek engagement with the detritus of American capitalism seems to be motivating a lot of the current crop of American comics artists. It’s what unites the work of Ben Jones, Johnny Negron and Ben Marra and it’s certainly what fires C.F. as well. However in Forgue’s case, rather than simply utilise, say, the layout and pacing of a computer game in order to bring structural freshness, or to find a new way of presenting storytelling beats, his use of these forms seems to be a way of observing and critiquing the forms themselves, as well as to question their place in our lives. His utilising of repetition in particular, that oldest of avant-garde techniques, seems designed to bring to the reader’s attention the similarities between the mind-numbing chug of computerised information we all access everyday and more Zen-like and desirable forms of ‘mindlessness’. One senses a yearning for meditative states in Forgue’s work; a desire to reach a pinnacle of oblivious contentment and to stay there for as long as possible.

Of course, this is only one person’s view. Anyone else’s experience of C.F.’s work will likely be completely different, and this is his major strength. In reordering and ignoring so many of the rules of the comic strip, C.F. creates work that is open to nearly infinite possible readings. Mere stands then, as a proper work of art in its own right, a surrealist magickal grimoire, a Zen-materialist critique and as a thorough exploration of the possibilities of the comics form. Not bad for a bunch of scribbles on coloured paper. **

Ben Jones’ Men’s Group: The Video is available now from PictureBox.