“It’s been so intense, so I thought you could kick back and not think too much.” An optimistic idea from the lofty mind of artist and writer Chris Kraus. It’s the second day of Aliens & Anorexia: A Chris Kraus Symposium at the Royal College of the Arts and, following a day of new interpretations of her work by other artists, this one is reserved for Kraus herself.

The author of I Love Dick, Torpor and Where Art Belongs, and founder of the Native Agents series of semiotext(e) –the iconic independent publisher credited with introducing French theorists like Jean Baudrillard and Felix Guattari to the US –the focus for the moment is on her 1996 film Gravity & Grace, a rarely screened feature-length fraught with difficulties during and after production. Struggling to get a release for the work, based across New Zealand and New York, Kraus eventually gave up on finding a distributor, instead penning Aliens & Anorexia, a non-linear narrative following its protagonist’s struggle to produce the film and named after self-abnegating philosopher Simone Weil’s book of the same title.

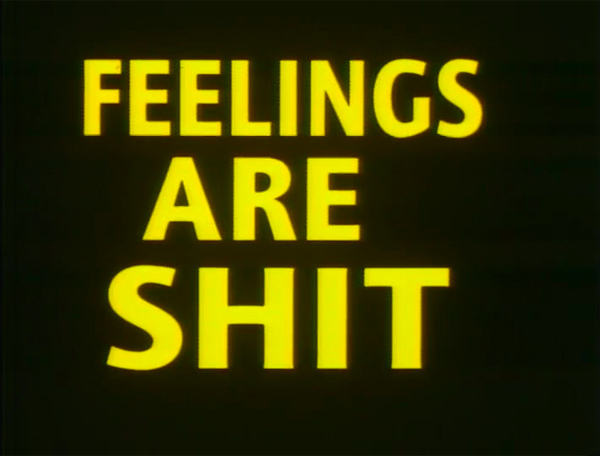

Gravity & Grace, then, offers fresh perspective for readers of Aliens & Anorexia, while highlighting the follies of those human interactions Kraus details in print; the clumsy mating ritual of a one-night-stand procured in a bar, the absurd curator, played by Kraus herself, brow-beating artist Gravity with feminist theory before ending, “frankly, your work just isn’t shitty enough.” As promised, the film is less concentrated than her writing, while still delivering elevated ideas with a warmth and wit, much like the artist herself. Hard of hearing, Kraus walks across the auditorium to her audience when answering questions, while explaining that Gravity & Grace exists in two parts (one with funding, the other without). Respectively, they’re based on flying saucer classic When Prophecy Fails by social psychologists Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter and a candid portrait of the artist as a young woman, following the “great disappointment” of a doomsday prediction unfulfilled.

Kraus’ strength lies in bringing together superficially disparate elements to her work; be it in I Love Dick’s bold self-revelation of an infatuated polyamorist alongside the gender politics of Downtown New York in the 70s or her credence of writing as performance. It’s in this way that Kraus reveals herself as prefiguring contemporary modes of interdisciplinarity in art, and its something that Gravity & Grace –a film made on a budget of $500,000, using film, at the threshold of the video revolution –represents. That’s not least for the fragmented visual aesthetic, utilising text, surreal imagery and privileging music in a way that resembles that of modern video art, spurred on by YouTube culture and home software. It’s here that Kraus’ role as artist, writer, critic, filmmaker and performer becomes indistinguishable and an emblem of what she calls the “expanding art world” pervading contemporary culture.**