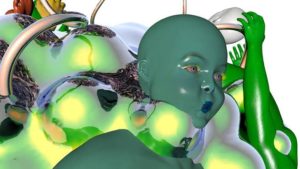

There’s more than a fleeting concern for the body beautiful in Goldsmiths Fine Art graduate, Eoghan Ryan’s Oh wicked flesh!. The culmination of a six-month artist residency at The South London Gallery, it’s an ambitious installation, working across media, that maximises the limited space to critique contemporary concerns with appearance, while commenting on the role of public art today.

Fittingly then, the viewer’s first encounter with the installation at the top of a stairwell, is a printed, stone façade copying the motif of Henry Moore’s newly restored sculpture in Kensington Gardens. Its historical significance mirrors Moore’s own concern for human endurance and his sculpture’s role as public art but, most importantly, it constructs a clear ‘entrance’ from the door frame.

An interior space lies behind it, wallpapered black with a pattern of flames and burns, in contrast to the airy sunlit room next door, where a goldfish bowl and posters are neatly ordered. Here, chaos reigns. As each frame of a video appears on an ultra widescreen projection, a loud click airs, announcing a step further into Ryan’s narrative, and a step away from the outside world. Footage bombards the viewer. At times one video directly layers over the other and it’s hard to see how the stories relate. A shot of bees pollinating flowers, an elderly woman in a hospital bed, even a dog show where several hands stroke a hairless canine. It’s tiring to follow but as the dialogue evolves, so too does the critical nature of Oh wicked flesh!. As a comment on Western Dualism’s belief in the mind-body divide, genetics and characteristics come to light.

Paper definitions of human body parts are splayed with descriptions of animals. Boxing matches are cut up by clips from dog shows and, as one of the breeder’s jumpers declares, the whole thing appears ‘Barking Mad’. Nonsensical, yet somehow incredibly relevant. At one point we see a man praying in a church. At another, a scan of a human body tracking liquid-flow to the stomach; a sharp visual contrast between Christian beliefs in a spiritual existence to those of modern medicine. It’s a deliberately inconclusive illustration.

“Going backwards and forwards, just trying to see if I resemble something human,” murmurs the central figure’s voice. He paints stripes similar to the dogs’ on his body and then comically changes his behaviour by openly pissing like the dog in a previous clip. Ultimately, the exterior appears to mean nothing at all, a fish is shown with the same stripes as him and the dog, mouthing aimlessly, trapped behind the glass of its tank. Then one of Henry Moore’s bronze sculptures, located near the South London Gallery at the Brandon Housing Estate, also appears in the film. Hidden behind corrugated iron, perhaps it’s to prevent it being stolen for its value as scrap metal, or simply to prevent damage to the public it was originally intended to please. Art’s worth appears fleeting, as do our looks.

Oh wicked flesh! runs at The South London Gallery from Tuesday, March 5 to Sunday May 12, 2013.