Artist, writer and performer Alexis Penney introduces a “new queer embodiment of deity” Dea Nova with 19 videos recorded during a three-hour performance showcase and a letter:

The past few years have been marked by my very public journeys and transitions through what felt like several lifetimes, onto a path that for me finally feels holistic and entire, via music, writing and image-making, often through social media, and performance creating, often within the folds of several interlocking communities and ritual forms. By leaving behind homes and communities, I found a true sense of home, and community, that transcends place. By facing and living with death, I’ve found what finally feels authentically like my life, or life herself.

Living as I do, as publicly and transparently as I can, I find myself the repository of questions, fears and anxieties about a lot of things: chiefly the idea of religion, spirituality and the question of deity and belief and how they are to exist within the context of our lives now. A reductionist, rational science reigns even while our cultural, social, economic and even psychic structures seem to be at their most irrational. Technology planetarily connects us and globally oppresses us. These are well-founded fears, taken in the context of our collective histories, many facets of which are still coming to light, and questions which don’t have simple answers, or maybe even answers at all.

“It seems to me suddenly that everything is a matter of perspective.”

For me, the practices of Wicca (bending, shaping), of yoga (union, yoking), of drag and even art, have all formed the syncretic idea of my life’s religion (reunion, reconnection) and practice, what I like to call informally my Circle: the infinitely permeable but contained system of meaning or agreements. It describes my experiences and those of others as they contribute to our shared realities in a way that makes everything – from sex to psychedelicsm, servitude and psychic pain – cohere and actually agree, even those facets that seem to want to nominally contradict. It seems to me suddenly that everything is a matter of perspective.

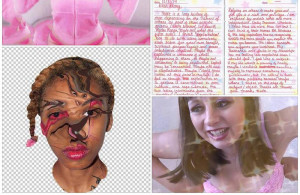

But who is She, and why She? I see and intuit within our shared histories, or herstories, part of our Thealogy, the denigration of woman, of the feminine – and even the creation of said division – as fundamental and essential to the way of life we can term patriarchy. Just as the denigration of blackness, the creation and conception of racial divisions, tribal allegiences, sectarian striation, class stratifications, and the traumatic split between human and Other-than-human, all these distinctions reify the regime we have been sold as the ultimate truth. I would never language patriarchy as wrong or unnatural, but unsustainable, as it threatens all other truths outside of its own, just as much as it threatens its own by actively destroying the world on which it attempts to stand apart. So, with care for my language, as non-violently as I can, I call myself a Transfeminist, someone who interfaces with the world through the experience of the dynamic and very trans feminine experience, the experience of someone forced to identify as a or many particular Others but who lives between the bleed lines, in the spans between momentary identities.

“I call myself a Transfeminist, someone who interfaces with the world through the experience of the dynamic and very trans feminine experience…”

Starhawk says, “The image of the Goddess inspires women to see ourselves as divine, our bodies sacred, the changing phases of our lives as holy, our aggression as healthy, our anger as purifying, and our power to nurture and create, but also to limit and destroy when necessary, as the very force that sustains all life.” But also that “all things are swirls of energy, vortexes of moving forces, currents in an ever-changing sea. Underlying the appearance of separateness, of fixed objects within a linear stream of time, reality is a field of energies that congeal, temporarily, into forms. In time, all ‘fixed’ things dissolve, only to coalesce again into new forms, new vehicles.”

The Goddess is a vehicle for our collective energies, our belief, a metaphor, for that’s all anything ever is, to describe what we are, beyond just you and me, though also within each of us, and with aspects singular and personal to each of us. Any two people create an energy through their connection and relationship, which changes if two become three, and so on. Chez Deep has been since her inception five, and not just a sum of five people or artists but an idea embodied within and somehow still transcendent of those five. Now, as we enter a phase of transitioning to being four, sending our sister Hari off on her own with love, the idea of what Dea Nova was, is and could be, beyond just the final collaboration between the original five of us, seems to be growing, disseminating.

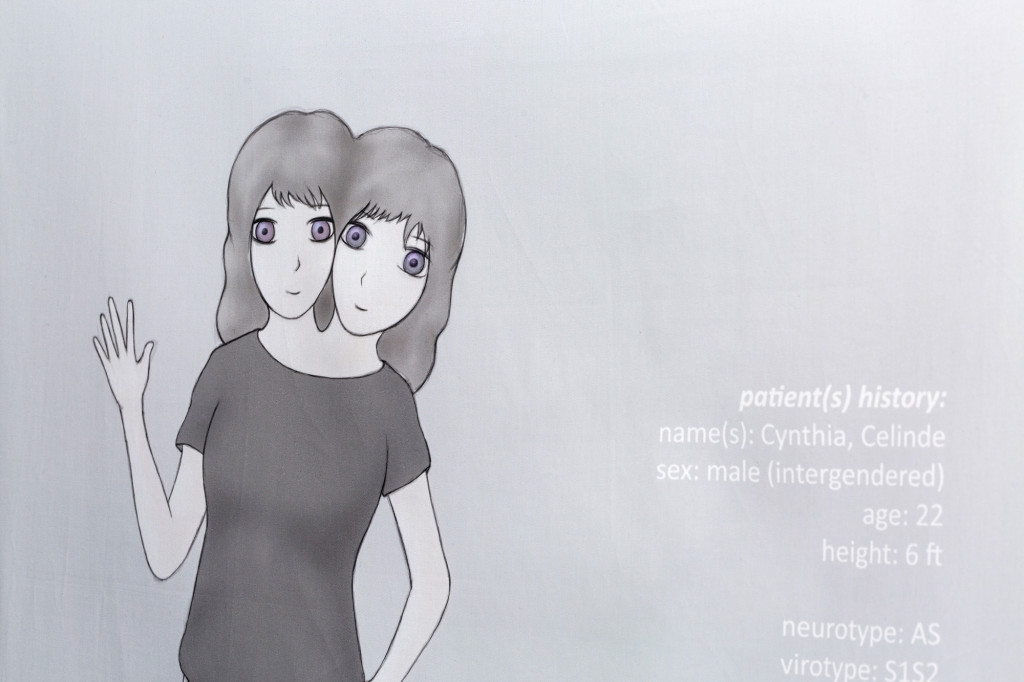

“What is a body anyway but a shifting ever-changing dynamic confluence of disparate parts”.

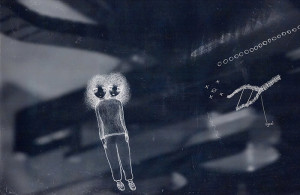

When I left San Francisco, I thought maybe I would never find another community that I didn’t necessarily create myself, for myself and my kin, and I resigned to that. But then I found myself existing in new contexts – within New York nightlife, collectively through Chez Deep and singularly as myself; within the world of Bathsalts, dually alongside Colin [Self] and singularly as myself; and I suddenly realize how many overlapping contexts and agreements a body can host. What is a body anyway but a shifting ever-changing dynamic confluence of disparate parts, mostly water, mostly bacteria and fungus and virus, mostly empty space? But also a body is always, already in conversation with a community, a super or meta-organism.

Dea Nova embodied that ideal for me. She came to me in a dream. Put these people into conversation. That’s it. Not just Chez Deep. Not just one scene but several. Just to see. Who are we? What are we? What can we be? It remains to be seen. As the landscapes of drag, and performance, and art, and technology, and our collective psyche, and economies of truth shift and change, I think we will see the rise and spread of culture, community and connection in ways both baffling and powerful affirming, inspiring and depressing.

“I think we will see the rise and spread of culture, community and connection in ways both baffling and powerful affirming…”

“'[w]hy are there two sexes? For the same reason we cut thecards when we shuffle the deck,” says Starhawk. But there were never just two, just as there was never just night and day, black or white. It probably made a lot of sense at many times and places, and the dualistic splits manifest within our cultures and worlds and psyches manifested, in my belief, exactly what they were designed to. But there is always still one. And one is extremely challenging. Because from one, we can count up to infinity, and never stop counting, but also implicit (and not opposite) one is zero. A circle. Or probably more apt, a spiral. It’s all a matter of perspective. So here is a bevy of perspectives, selected here but fully accessible in its entirety – 19 performances in all – to be accessed in whatever way makes the most sense to you. A huge thank you to all the beautiful and inspiring and powerful women and people that have made my journey home to myself, in New York, right now, so baffling and inspiring and frightening and joyous. I would like this to also be a challenge to you, in your community, wherever you are. Show us who She is to you. Show us your meta-organism. A time looms when we will all be called upon to be our own Messiahs for ourselves and our kindred. I want to hear what you have to say. I want to see your drag.

Starhawk says, “Decide what is sacred to you, and put your best life energies at its service. Make that the focus of your studies, your work, the test for your pleasures and you relationships. Don’t ever let fear or craving for security turn you aside. When you serve your passion, when you are willing to risk yourself for something, your greatest creative energies are released. Hard work is required, but nothing is more joyful than work infused by love.”

Satnam and blessed be!

– Alexis Penney

share news item