Berlin’s TLTRPreß has released the latest issue of The Yap, first printed in March, with an excerpted interview from the zine re-published on AQNB today.

Led by Ondřej Teplý, The Yap’s 77th edition addresses printed media in the digital age, musing, “can publishing projects also experience a mid-life crisis?” Focussing on the subject of independent presses from the perspectives of a writer, book designer, and a performance artist, the project features interviews with Habib William Kherbek, Monika Janulvičiūtė, and Ivan Cheng, who discuss their recents projects and experiences working with publishing houses such as TLTRPreß.

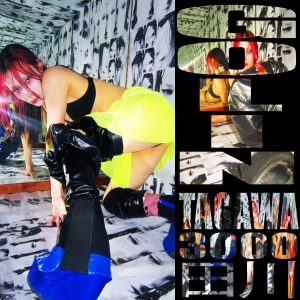

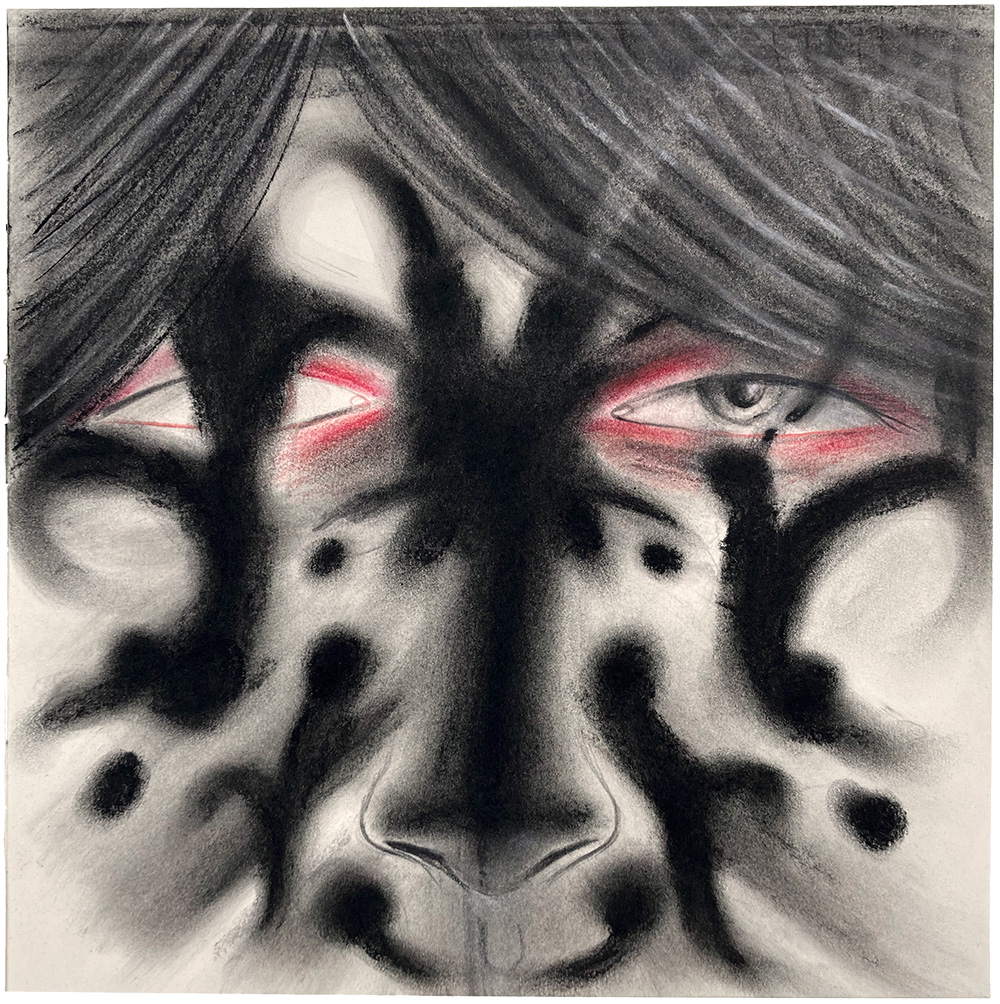

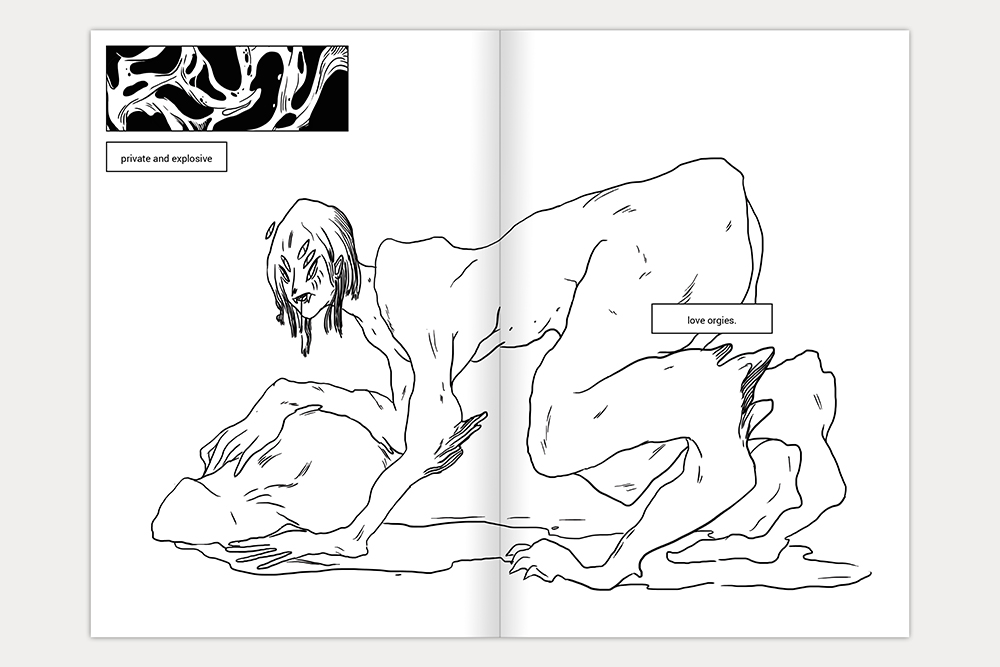

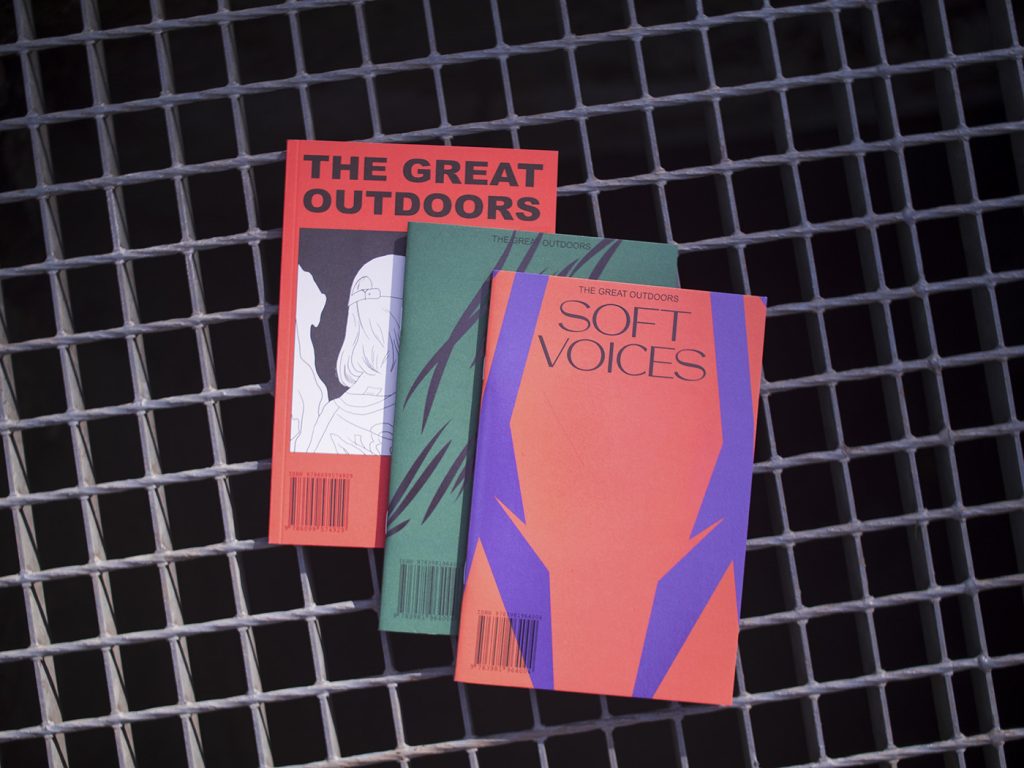

In the final interview with Monika Janulvičiūtė, up today on AQNB, the designer and artist discusses collaboration, seeking touch through printed media and her book design for Habib William Kherbek’s STILL DANCING, published in 2021 via TLTRPreß. Janulvičiūtė’s practice is broad, spanning an array of outcomes. There’s video work such as ‘Water Striders’ with Antanas Lučiūnas, premiered by AQNB in 2020, featuring a video game-like first person exploration of derelict industrial buildings and farm estates. Or the uncanny fiction of her TLTRPreß book The Great Outdoors (2017), which examines desire and cosmic orgies. As a designer her work challenges established publication formats, most evidenced in her work on STILL DANCING, in which Janulvičiūtė converts the digital elements of social media into a material object.**

Read the excerpted interview below and see TLTRPreß for more information.

—

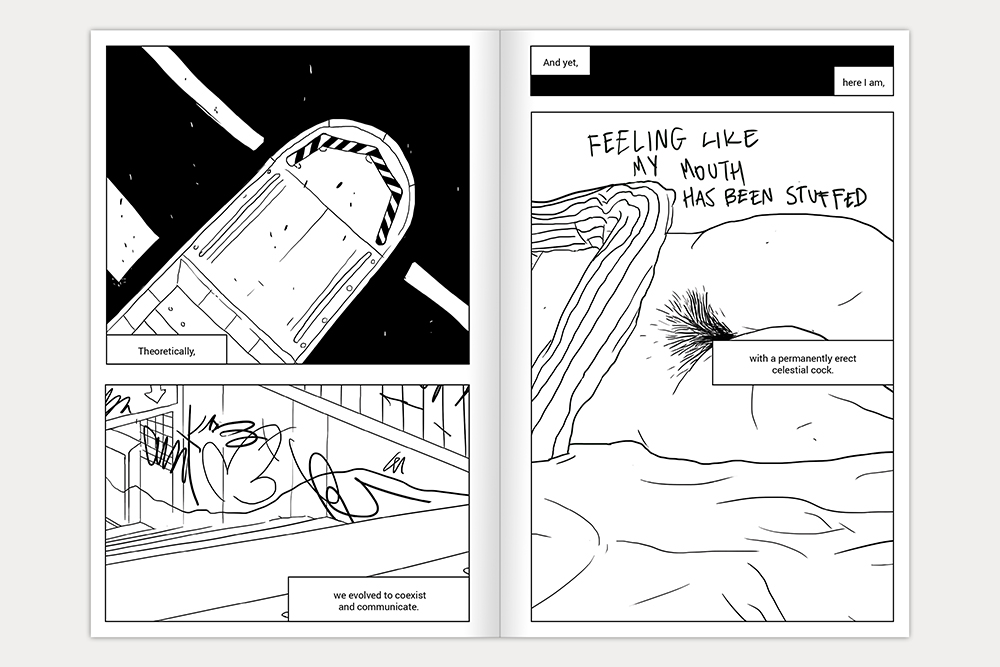

Ondřej Teplý: Still Dancing has a quite specific design. It’s long, slim, and flippable – you can read it from both ends. When I talked to Habib William Kherbek, he described the whole idea of an infinite scroll of Instagram standing behind your design. How was it for you to transfer digital elements into physical, paper form?

It took around a year and a half to make such a book. From the beginning, all three of us, me, William, and Martin Kohout from TLTRPreß, were leaning towards a landscape format. Such a format isn’t common for books at all, but it has undeniable qualities, especially when it’s flippable. So that was our natural reference. Funny story, I accidentally exported the book as spreads, but Martin and William thought it was single pages, really long pages. It was a misunderstanding, but they both liked it, and they were like “ Why don’t we do it longer?” I was like “Oh my god but it’s extremely long!” Nevertheless, later we encountered a few limitations. As an independent printing and self-sustained practice, you just try to fit into standardised sizes and modes of printing, because, if not, it’s quite costly and it requires many more steps in the chain of production. I knew that the long landscape shape is complicated, but what I didn’t know was how many negative answers we would receive to our order. After this experience, we ended up deciding that it should be Riso and that we would print it in Prague at Kudla Werkstatt. In the end, it was a more traditional manual assembly. The whole process was quite loopy, and we knew that we would have to sacrifice something to finish the project. We sacrificed time.

Lately, I have been interested in film and video essay-making, and, because of that, I can see a lot of similarities between audiovisual work and books. Montage and video editing are, in my opinion, similar to designing a book layout. That’s why these two mediums don’t seem so far from each other. The book’s animation and its flippable format, which enables the reader to choose the way of reading, are the elements that bring some of the digital experience into physical paper form.

OT: As you indicated, you are a multimedia artist with a broad field of interest – from graphic and audiovisual work to architecture. How do these various media influence your book design work?

It allows me to see the new projects more openly and not to have an a priori fixed idea of what I want. The openness is also supported by the fact that most of my work is collaborative, except for commercial stuff. On the other side, the works that are less graspable, not straightforward, in a sense of artistic quality, are collaborations. It allows me to discover an interesting and sometimes even unexpected intersection between different fields. Personally, it helped me a lot in my praxis; for instance, from designing fonts to making furniture. It can be exhausting, but, overall, it has its quality and what is most important is that it’s super entertaining.

OT: Collaborative work has lately become an important issue. The urge to erase today’s hyper-individualism in the artistic community is omnipresent. As you mentioned, your work is based on collaboration. Is the intention only practical, or do you use this type of work also because of the aforementioned reason?

I think it’s difficult to hold a collective together, so I prefer to do more interpersonal types of collaborations. For example, both books from The Great Outdoors series for TLTRPreß were made in collaboration with writers and other artists. Not that I wasn’t capable of doing it alone, but working in the collective helped me to capture the right moment in time which I was seeking unconsciously. Such work is, in the end, much richer and more saturated than doing it solo. Besides, working in a collective can accelerate the workflow, and you can also receive immediate feedback. When producing books, you want people to desire them. That’s why I always find it weird when people don’t send pre-final drafts, or even a few pages, to their friends for general tastes, not even necessarily proofreading. There has been so much energy invested already. And you simply want to have someone who will root for your work.

Sometimes you just need more time to find out what works for you, like in my case. When I was a beginning designer, and, later, a beginning artist, the pressure on being hyper-individualistic was very strong. However, I felt like this wasn’t for me, even though the pressure was telling me the opposite. It took me quite some time, and a lot of courage, to internally refuse the individualistic type of work and accept the fact that being collaborative doesn’t mean being weak, or being unable to do it on your own. With the rise of social media, an additional pressure appeared – it was desirable to be collaborative, but only with a certain type of hyped and cool people on board. It ruined it a fair bit, to be honest. It did set back the whole thing, but now we know better, I guess.

OT: What’s the difference, from the perspective of a book designer, between working for an independent publishing project and a commercial one?

It adds a certain freedom in the sense of being involved in the project from its earliest stages. On the other hand, it’s probably rarely giving the freedom of printing something outrageous. However, finding a printing company that’ll be able to produce [the book], and for a good price, you feel like you’ve hacked your way through. For me, it’s always so charming to see something on paper. There’s still a lot of magic when you’re working on a project for a long time. You know everything by heart, and then it lands up in a book: a physical object.

OT: Collaborating with independent publishing houses certainly raises the question of the materiality and tactility of paper in our post-digital age. What’s the difference between designing an ebook and a physical paper book?

Well, there’re many technical differences, but I get it’s not the answer you’re seeking. What I like about publishing, in general, is that you never know where your work will end up. That goes both for books, ebooks, films, and posters. You are overpowered by their circulation. I remember, it was already a few years ago, when I went to someone’s house and I found copies of books designed by me on a bookshelf there. That’s enthralling. Our fingertips seek for touch, we should remember to divert it from steel and glass and plastic routinely.**

share news item