As of January this year, after many attempts to secure a baseline income, AQNB has had little choice but to reduce its publishing schedule and consider how, if at all, it can continue to run as a platform. We tried selling advertising, awkwardly navigating the invisible relationships and class distinctions that that seems to entail. Then we set up a production services arm, which worked to a degree but with no real surplus to cover the cost of running a website. We also increased our free labour (there was always free labour). Finally, we naively or exhaustedly placed all our hopes in a public funding bid. The rejection email came on January 31, two weeks earlier than expected on the eve of the Super Blood Blue Moon eclipse, a very rare occurrence. I was still recovering following spinal surgery a week earlier—a successful attempt at relieving what had been a year of severe and chronic pain. I’d sustained what my surgeon described as a “massive” disc herniation that was no doubt caused by the sedentary life of an overworked writer and a few too many cycling accidents in a city where public transport is expensive. Astrology would inform you that this first of two eclipses that opened 2018 brings closure and resolution—a turning point.

The reason I linger on these personal details is not to bemoan my misfortune or lament my lack of privilege (I have plenty) but more to describe what it takes to survive solely on freelance writing, while editing a busy online publication. I’m a 33-year old journalist and author with 10-plus years experience and I live off an annual income that’s less than half of the national average. I’ve been involved with AQNB for seven years, editing it for five, and my future looks more precarious than ever. There are perks to the job and sacrifices have to be made to do what you love, but the downsides become less manageable as you get older, and as I have found, healthcare is expensive. The print industry as a whole appears to be disintegrating fast, online publishing might never resolve the issue of monetizing itself and I’m reaching an age where my employability for entry-level jobs in other more stable industries is also diminishing. I have to make a choice, and, even now, with so little to look ahead to and a site that has become a burden of unpaid labour, I still want to find a way to make AQNB a viable space for the artists, writers and readers it aims to present and support.

When I started, I was new to London with few to no connections and very little knowledge of visual art. I was primarily a music critic who mostly wrote for print in Perth in Australia, part-time, specialising in rock music. In my new cultural environment, I quickly learned about electronic production, while becoming acquainted with the internet as both a medium and a space for disruption. In moving to another country and essentially starting over as a journalist, I also learned what to expect from independent media, which wasn’t much at all. One of my first commissions was a feature with a well-regarded publication, which had been a long-held dream that I achieved within months of landing in London, sooner than I expected. It didn’t pay very well but it was better than the nothing I would get from a number of other popular magazines (some of which, incidentally, are much bigger now and still don’t pay their contributors). I would build up the experience and portfolio of having written for better-known, even respected publications under one name, while redirecting my access to review copies and artist interviews by producing pieces for a site that I wrote for under another. It was called AQNB and would eventually become a labour of love.

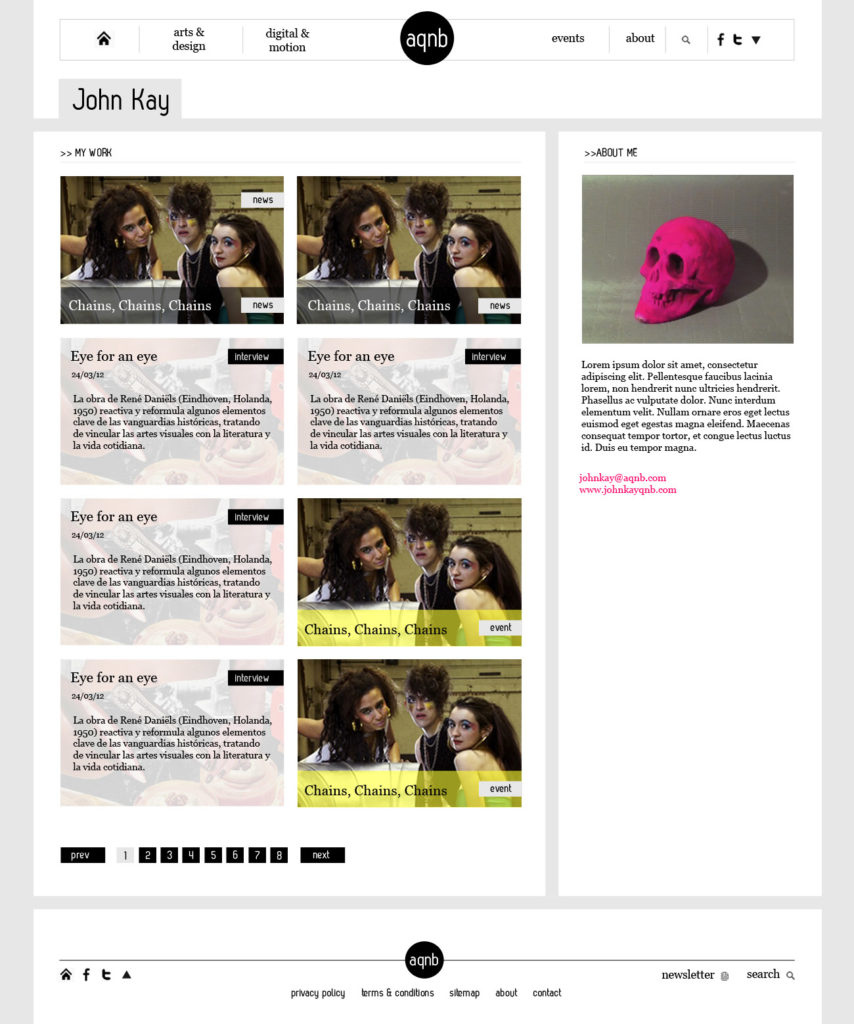

I came to the site – which was a very different beast back in 2011 – while signed up to an online platform called peopleperhour.com. It’s a kind of TaskRabbit for freelance writers where you bid on an advertised copywriting job against other anonymous bidders, at the cost of a membership fee and a percentage of the commission. For every “Ghost Writer: Living Life in a Rice Bowl” and “Talented Writer sought to write topics related to the Lesbian community” job, there were hundreds of mundane ‘content generation’ tasks, which were often lost to less qualified writers who would work for considerably lower fees. For one short-lived commission writing weekly tech reviews, I got stiffed after I’d already submitted the work. Another one paid $5 for 500 word hotel reviews, which obviously wasn’t worth my time when living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. A more promising proposition came in the form of a Spanish client who called himself “Don Tercio”. He was looking for a “subculture and arts writer” for his speculative blog project that seemed to cover, or tried to cover, everything. I was encouraged to use a pen name (Jean Kay) and after submitting a trial piece it paid £30 to £40 a week to write one article on anything I wanted. It was something.

That job carried on for another year, while I hustled other work and got by, I don’t know how, until at the end of 2012 Don made me the editor. We worked together on the not great template design that existed before this one – the cheesy zag font and an unmanageable array of navbar topics included. My income was bumped up to £400 a month, £100 a week, for managing a small team of mostly inexperienced writers, and writing and publishing two “news” posts a day. I had no job security and would meet my mysterious benefactor two or three times a year. The pay, though, almost covered my rent. I supplemented that by interning at another publication one or two days a week for a £25 per diem, writing for others sporadically and working weekends at the notoriously disorganised haven for struggling artists and writers, Music & Video Exchange in Notting Hill. One of those jobs lasted three months, the other a year. By that point, the average I could expect for a few days work on an interview feature elsewhere was £50 to £100.

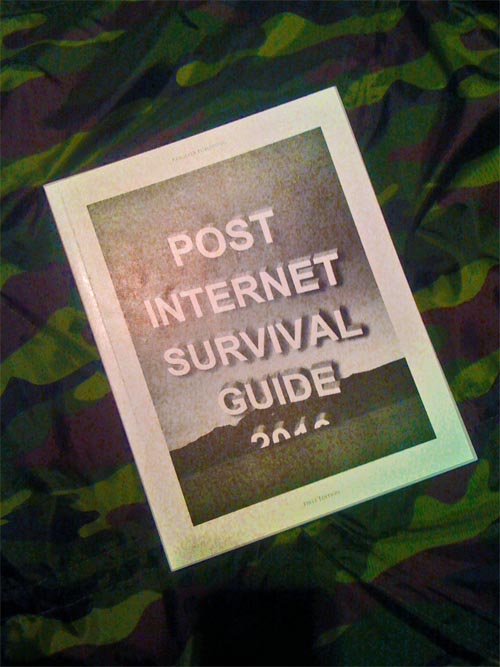

In that time, my AQNB remit had expanded beyond music and I was starting to look for art to write about. Anything particularly well known wouldn’t do because who would read about an established artist written by an unknown person from an unknown publication? It also wasn’t very interesting. So, I would diligently trawl through Twitter accounts (Instagram wasn’t a thing at the time) looking for artists with interesting identities, watching their interactions, checking their websites and occasionally emailing one for an interview. Katja Novitskova was one of my first-ever visual artist Q&As, after which she would send me a copy of her Post Internet Survival Guide and I would be introduced to an entire network of young, interesting and interested artists who were critically engaged with their work and their context. I was hooked.

Don would support my decisions, giving me full control over the editorial line with little interference, while providing me with a budget, however small, and a website, however inadequate. It was a unique set of conditions that led to a unique website and over time it coagulated into a community. I brought my experience as a writer and music critic to a nascent art scene, while often commissioning and working closely with artists and art enthusiasts with little writing experience because there were few journalists who knew what most of the things we covered actually were. Meanwhile, I had the opportunity to learn to be an editor, and gain experience in online publishing while on the job, eventually advancing to co-director of AQNB. No matter the incalculable hours of overtime that entailed, it’s an opportunity for which I am eternally grateful. Don, though, dropped out in August 2017 – the month of the solar eclipse – to pursue other projects, leaving the rest of us to fill the void.

In the five years that I’ve shaped and led the direction of AQNB, I’ve seen its audience and community grow in visible ways. With Caroline Heron’s arrival in 2013, we set up a production services arm, the pay got better and the operation ran smoother and more frequently. Our team was then completed in 2016, when HP Parmley joined as deputy editor and moral compass. Together we worked on, paid for and launched a new website design with the help of graphic designers David Rudnick and Harry Bloom. We now have a healthy social media following, decent traffic and a vast network of artists, curators, producers, and musicians; galleries, artist spaces and institutions; venues, festivals and labels. I answer hundreds of emails a week, commission editorial pieces by mostly early-career writers from around the world and take part in a tightly coordinated production line of in-house copy. It’s shared and administered via a series of spreadsheets managed by myself and my two committed and hard-working colleagues.

Although never explicitly communicated in any real, public way, the objective of AQNB has always been to create and maintain an independent platform in support of underrepresented voices and marginalised perspectives active in the arts today. These are namely feminist, queer, and POC ones, with additional focus on class, and mental and physical health, while being anchored in a broader context of contemporary critical discourse, political theory and online culture. I have no doubt that the site has played a role in both recording and galvanising a niche of multidisciplinary and internet-aware art as a globally networked community.

It is only through the dedication and generosity of everyone involved that AQNB manages to continue. However, in figuring out ways to raise enough money to pay for everything it takes to reimburse writers for their efforts, run a large website and provide editorial support, we’ve hit an invisible brick wall. On the other side of this wall are the media behemoths with established networks and dedicated teams that agree corporate partnerships and—importantly for us—command what small budgets there are for paid advertising from (halfway relevant) cultural outlets.

I don’t hold anyone responsible for AQNB’s struggle to sustain itself in 2018. I would, however, like it to keep running. I would like to be able to keep running it. I would like it to exist as an antidote of independence in the face of an intensifying corporate stronghold of creative labour; as one that works in collaboration with its artists, administrators, and audiences in maintaining a creative space outside of commerce. I also suspect that there are a few of you out there who would like that too.

We will continue to redirect money we earn through services for other arts organisations. We will also continue to ask larger galleries for advertising when approached and apply for public funding to support discrete projects. However, we must think of ways to better support the platform on a day-to-day basis. Therefore, we have set up a Patreon in the hope that as a community we can support one another through regular small donations and voluntary subscriptions. All the proceeds will go directly to commission and edit new writing from our network of contributors and keep what we believe to be a dynamic and vital conversation going. With your help we hope to assign more pieces, be more ambitious and generally respond to you, the people who value the work we feature and want to see more of it. This month, Mars – the planet of energy, action, and desire—goes into retrograde and the cycle that started in August and ended in January is reaching its conclusion. It’s up to all of us to decide what that is.**

To be continued…