“Oil was discovered in the mid-1800s…” opens Hayden Dunham with a smile when I finally turn on my smartphone recorder in the restaurant of the Standard Hotel in Los Angeles. It’s around 10 pm, six hours since we’d first met in the locker room of a 24-hour spa in Koreatown, following a series of unpredictable exchanges over a week, first through Instagram DM, then email and finally a number of minutes-long voice messages sent between inboxes. “Time is really different right now and it’s kind of preventing me from living in a linear way,” Dunham says in one of these audio files titled ‘JK CONVERGE 2,’ apologising for dropping out of touch and citing a number of ‘bizarre’ emergency eye operations that had left her temporarily blind on one side and unable to look at computer screens, “everything is a little bit more scattered.”

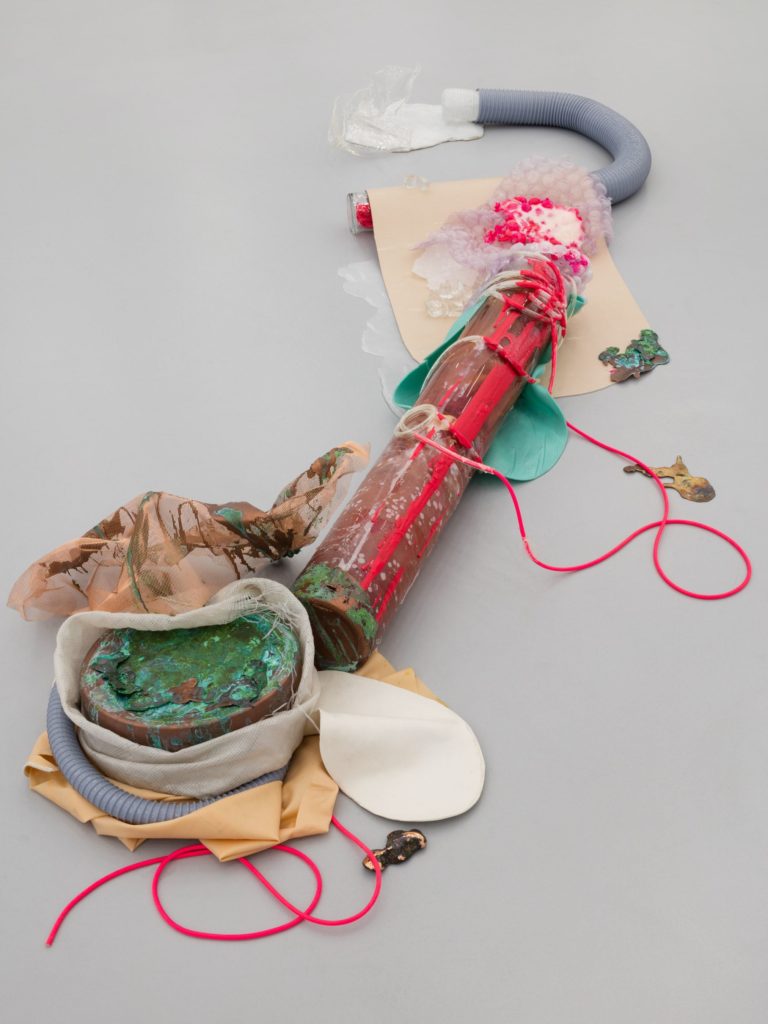

Ostensibly, Dunham and I are in the Superior Oil Company headquarters-come-boutique hotel downtown to talk about her work. She has a series of sculptures showing in the Corpus Alienum group exhibition at Hunter Shaw Fine Art in LA until December 7. There, wall hung vaporizers titled ‘GEL (liquid)’ emit clouds of an unknown substance at the entrance. A piece of aluminium piping snakes out of a swathed and crumpled bundle of hard porcelain, plastic, foam, glass called ‘SILT.’ It looks like an animate thing that is drooling a clear stream of solid platinum silicone – synthetic and frozen in time, petrified but alive.

“There are a few things about oil that really excites me, and one is that oil is made from the petrifaction of living matter, so there are pockets that cover the earth of this material that was once living and now is decaying, and when it surfaces it creates a lot of energy,” Dunham says after breathlessly running through a detailed and uncannily accurate history of petroleum: from its discovery in a preindustrial era still powered by animal fats, the force of kerosene, Thomas Edison’s first demonstration of the light bulb in 1879, to the intersection of economic and political interests that fuelled the mutual development of the oil, automotive and military industries in the United States. “When I first started thinking about that I got really excited about the reflections also between human bodies. These pockets of shadow material inside of our own bodies, hidden deep inside of us. And yet, when this lower-den material comes to the surface there is potential for an incredible amount of power,” she says about the conceptual idea of emotional trauma lurking in the unconscious. “In the case of oil all it took is a flame, a spark to translate the material into a new kind of energy. I get really excited about these energetic systems, energy in general, energy as a means of exchange.”

This isn’t a conventional interview by any means – a spa date that came as a kind of dare on the phone on the day of our meeting, tempered by my refusal to do it in the nude. “I tried,” Dunham says in the canteen in our matching oversized beige shorts and yellow shirt outfits with ‘Wi Spa’ emblazoned across them. She swipes for an Aloe drink with a digital wristband she not once describes as ‘cute’ then leads me to a warm room of clay balls the size of marbles. Lying down, Dunham says something about thanking the clumps of low-fired mineral compounds for their help and points out the activated charcoal ceiling above us. It’s a substance she used in an earlier group show at ltd los angeles, closed in September and featuring her ‘HROUGH’ installation. “It was really wet, it was literally, like, dripping,” Dunham clarifies what appears to be an important point about the piece, also composed of tourmaline and volcanic ash, and presented on a metal structure that resembles both Pilates equipment and a bondage rig.

“I think that if I didn’t believe that objects had the ability to carry energetic content, I wouldn’t be interested in working with objects. If I thought that this was a glass that couldn’t transcend its form, I probably wouldn’t be interested in it,” she says, gesturing toward the Standard Hotel tableware, when asked whether she believes the things she makes have their own agency. “When I’m thinking about materials, like in my sculptures, I’m really interested in facilitating them in a way where they’re beyond the form. It’s not like, ‘this is made out of silicone,’ it’s more, ‘is that a living… what is that?’ It’s beyond itself. In making sculptures or making physical ecosystems, sometimes it doesn’t work, so a lot of it is about the failure and why, and what the cross-section is; what happens there?”

The music is loud in the Marigold room. My phone is placed on top of another glass close to Dunham, face down to divert the severe light of its liquid-crystal display from her eyes. On listening back to its recording, it occurs to me that the first song to play during our conversation is ‘There is No Other Way’ by Blur. ‘Blurriness’ is a major theme of the continued exchange with Dunham, whose communication style could be described as mercurial, while at one point an iMessage malfunction across my devices coincidentally means her voice texts evaporate before I even hear them. At the same time, there is a strong sense of intentionality, intuition and even providence to Dunham’s work and attitude, as well as this conversation. “It might be trying to find ways to be here,” she says when I ask about her relationship to her own body and this intense interest in energy exchange and shifting forms. “Or like, to operate in this host form. I guess augmentations really help me to be here. Pools of warm water really help, rooms with clay balls that are like earth, or augmentations of earth. I think it is helpful.”

To make sense of where Dunham is coming from, one should defer to a kind of pantheistic understanding of the universe, where all information networks, ideas and systems of control are linked and related — intricately, inextricably, energetically. When speaking in the hotel, she hits on points from a broad spectrum of associations that are deeply compelling. They expand and contract in terms of specificity and rationality, proposing powerful relationships between war, capitalism and the pharmacological industry, in the same breath as drawing on science, astrology and mythology to support an ambiguously proposed idea. “It’s really interesting because Seven Sisters is a really particular area in London where I work,” she says, following an account of the consortium of multinational oil companies – also called Seven Sisters – that formed a cartel in the mid-1940s to the 1970s, controlling 85 per cent of the world’s petroleum resources. “I also remembered Seven Sisters is actually in Greek mythology, about these seven nymphs who are all on earth and all have really different storylines, involving different elements of water but they all have the same fate, which is they all died and became stars. And what is a star? A star is a finite amount of energy that is burning but will burn out. For me, there is an intense and really exciting comparison between that light from the star and also the light that oil is making in the world. I really saw this light, this kerosene, as a symbolic moment when humans started to change their relationship with the earth… humans started topping the earth.”

Given Dunham’s degree in environmental science, applied psychology, advertising and gender / sexuality at NYU’s Gallatin School, along with other more esoteric interests (one of the first things she asks me is my star sign), her fiercely universalist, cross-disciplinary approach comes as no surprise. It carries into an ongoing and equally process-driven music project called QT, a pop star performance that surfaced in 2014 as Dunham with different hair and an augmented appearance in a pink-and-purple-hued music video for a single called ‘Hey QT.’ Produced in collaboration with Sophie and A.G. Cook and released on XL Recordings, the song’s combined YouTube views reaches into the millions and the music video – produced by Bradley & Pablo – features a figure hooked up to miscellaneous slimline technologies in a brightly-lit, glass box, dancing to the freakishly animated pitch of a vocal repeating, “I feel your hands on my body/ Every time you think of me, boy.” The video is interspersed with slow-motion CGI renderings of a sparkling fuchsia liquid, distilled from human emotion and coiling upward around a narrow soda can branded ‘QT,’ an energy drink.

“I’m really interested in content, it’s not linear, the way that it looks at all, to me,” Dunham says, refuting the suggestion that the conceptual work – with its strong stylistic element that also crosses into her sculptural practice – is an aesthetic pursuit. “It’s more like, ‘here we have this energetic substance, this energy drink; what is the physical representation of this substance? When you look at the physical representation of the substance, can it create the same energetic boost as when you consume this substance? Can you make another product, like a pop song, that can raise someone’s energy level when they listen to it? Are there able to be these cross-contaminations?”

QT hasn’t released another song in the three years since ‘Hey QT’ first came out. And yet that track’s repetitive, mesmerising composition of crisp, clinical beats and an overwhelming, almost toxic positivity, has made it an essential staple in the roster of creative affiliates PC Music. “It’s more of a feeling, that is, what I desire to feel,” says Dunham about what inspired this attempt to sublimate the effect of an energy drink in a pop song. “Marketing aside, if you think about Taylor Swift and when she released that last album [1989], she had this Coca-Cola commercial. ‘Welcome to New York’ was playing and the commercial is her drinking a sip of Coke and then a cat appears. Then she drinks it again and there’s a second cat, and then it triples, and then it quadruples and then the whole apartment is full of cats and she’s drinking it, and drinking it, and drinking it, and you see her repetitively drinking the Coke. I’m really interested in what happens when you are in the store and you see the can of Coke. Is it possible that something cross-sensory happens where ‘Welcome to New York’ is stuck in your head, or when you consume it actually you feel like Taylor? There’s this opportunity for something outside of the physicality to happen.”

This outside effect of ‘Hey QT’ is visible in QT fans’ significant reaction when she appeared on stage for a PC Music showcase in LA last year. There she lip-synced to her one and only song for about four minutes, on a bill that included established pop stars with a substantially larger musical repertoire like Charli XCX and Carly Rae Jepsen. All this at the same time as promoting a limited edition QT energy drink that actually exists in physical, drinkable form at an event sponsored by Red Bull. “The stuff that I get really excited about, also thinking through these corporations, are the different relationships that had to happen in order for these things to be facilitated, all the structures that enabled these things to travel, or for these cross-linear things to infiltrate.”

Infiltration is unquestionably a core concern for Dunham, one that she herself attempts to examine and even replicate. Her exposing and specific choices of interview location come across as much an experiment in the power of vulnerability as it is a meticulously coordinated tour of the networks that so preoccupy her. “I like looking at those structures. I like it when they’re made visible too because so much of it is invisible, even thinking through this building,” Dunham says, signalling the dimly lit restaurant in the Standard Hotel, glowing golden. “The temperature is regulated, there are so many systems of control within this that are not visible and that are actually inside the walls, and I think that a lot of that is happening within our bodies. Like when DuPont makes Teflon and the by-product is C8 and then C8 is distributed into the waterways in Ohio, which then link to other waterways. Sixty years later, now it’s in 98 per cent of Americans,” she continues, once again demonstrating her typically comprehensive research with extraordinary precision. “It’s really interesting because this thing is not visible and yet leads to all of these differences inside of our bodies. Those dialogues that are happening, where we are actually the host of those conversations, manifest in different ways, some are consensual and some are non-consensual.”

Leading me on a tour of the rest of the Standard Hotel – a prototype handbag made from icepacks on her shoulder – Dunham takes a moment to gaze at a tableaux of an oil refinery above the entrance before ushering us to the rooftop with its spectacular view, house DJ and communal waterbeds. She tells me these odd capsules for intimate public lounging, that she references a number of times throughout our meeting and correspondence, are her favourite part of the building. “Water has the ability to separate and still remain connected to the whole,” she says, on the question of how one can consolidate such a vast material perspective with what seems like a clear political impetus. “It can change forms multiple times, it is expansive and also can be held. Really, what I am working towards is being more like water in my life and my approaches to being here… Water is also easier to identify with because it can also become hard, it can be like ice and you have to wait to be melted. It can also be vapour, where you’re fragmented and no one can ever see you, or hold you, or be close to you… It’s still the same material, it’s just going into different states and that dialogue continues for the duration of its stay here and I really feel that way too.”

It’s through this analogy that one can almost grasp the scope of Dunham’s work. It goes well beyond an art practice and this deftly planned encounter into the very substances that both support and inhabit them. “I think it goes back to the larger structure, what’s actually happening and how those conversations are being held, what they’re being held by. That’s also an opportunity to look to the buildings or the structures that we’re within; to think through new ways of infiltrating, creating systems within systems. They’re questions of, ‘is it about actually taking down an entire system and rebuilding it from the ground up, or is it more about assimilating and then going from top-down?’ These are all questions that I’m constantly engaging with in terms of my work and it’s ongoing, it’s research.”**

Hayden Dunham is showing as part of group exhibitions Corpus Alienum at Los Angeles’ Hunter Shaw Fine Art, running November 4 to December 7, and STRAY for New York’s Time Square Arts, running December 1 to January 29, 2017.