“I just wanna take a shit on it,” says Ser Brandon-Castro Serpas about the bland, violent whiteness of art. Speaking over video chat, the poet, artist, former activist and model, as well as beloved friend, is taking part in the Prick up your Ears group exhibition at Karma LA, which opened August 5 and is running to September 9.

Born in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights and currently living in Brooklyn, Serpas first found a sense of agency in community activism. However, around the time she began physically transitioning, Serpas not only moved away, but also shifted into art from organizing, feeling marginalized for her gender nonconformity (GNC, henceforth) and seeking space from the violence of local respectability politics. Of course, the marketized brutality of New York City and its art scene, along with the over-professionalized approach to creative production of Columbia University, was no salve. Serpas found that an even more intense assimilation to normative behavior and appearance was expected of her, tying into a general expectation for GNC trans fems to be High Femme™ — too often looking like the imposition of white aesthetics — that barely differed from the expectations to butch it up and wear suits to organizing meetings back in California.

Disillusionment with her old and new home, as well as a rejection of nostalgia, have influenced Ser’s approach to her work. She isn’t precious about expression, but she finds her process — involving hoarding and layered reuse of found, gifted, and stolen fabrics as well as manic mark-making — to be cathartic, even scatalogical in the face of constant colonial transmisogyny. Despite her hatred of the art industry, she found a degree of non-control and openness in making that allowed her to finally unclench after years of model minority assimilation, which she has called a “myth of mestizo excellence.” Indeed, the poop metaphor goes further than a gesture to prostate pleasure or the sweet joy of release; it also ties into a deeper distrust of both facile intuition and inane analyticity. In the limbo between hedonism and austerity, gut feels and heady dissociation, Serpas finds herself stumbling on a politics of self-critique in contrast to the respectable, legible, visible expectations imposed upon her.

The text presented here is part of a conversation that goes for a little over an hour and covers a number of topics: the brutal, colonially-inflected upbringing of many latinx gender nonconforming people, the freedom that comes from relishing what the world deems abject, and the violent absurdity of regimes of visibility to which black and brown femmes are expected to assimilate.

** So let’s talk faeces first, maybe?

Ser Serpas: Okay, so, as a child I was just kind of a loner, despite never having any alone time or privacy. One of my earliest memories is playing a game on the Gameboy for hours in a packed house with a busted toilet. And I couldn’t hold my shit, and it fell down my corduroy pants and I just kind of stuck it between two VHS tapes on my mom’s dresser and hid it. Or five years later in a less-cramped but equally un-private apartment, I would shit in the shower which had this grate, and would push the shit down into the grate with my fingers and just kind of revel in it. Plus there’s an erotic aspect to holding it in as long as you can. And playing around with it is something I still do, like when I’m somewhere random — usually Colombia, somewhere bougie — I would just be like, fuck it. And I think that’s the way that I write and make. I like shit a lot. The stresses from the day out, I kind of just fit them into a grate, and I enjoy the process; I always feel like I’m getting away with something.

** What is that? Is that like imposter syndrome? [ed. note: this syndrome describes high-achieving individuals marked by an inability to internalize their accomplishments and a persistent fear of being exposed as a “fraud”]

SS: It is imposter syndrome kind of, but it’s also literally just like taking a shit where I’m supposed to be comfortable, or a happy student, or like content with my school experiences. It was just like, ‘oh, you’re getting like a full-ride because your income status, but then also because you’re documented and also because you’re this like golden mestiza.’ And you’re just kind of there and I just wanna take a shit on all of it. So it is imposter syndrome, but it’s also just the feeling of like, I’m kind of just relishing my own shit and not disgusted by it. And I still eat my boogers — maybe it’s that I don’t take care of my health, but then I also have to feel that the ways to stay healthy and be clean etc is related to this white humanism that I guess I never really felt, a need to participate in. Especially early on, I was just a gross loner, but I don’t know, now I’m writing and usually not editing at all and writing like white girls on the train. And the resistant frame is just a frame, it doesn’t structure the work — you just kind of get in the right emotional moment and do the thing, but you don’t structure it, it’s not analytical. You don’t practice doing the same stress expelling thing over time and develop it into a style, you just let it be its own thing, let it just be taking a shit.

** Some of your drawings, which you’ve stated you’ve begun producing more frequently lately. You also state that your drawing practice exists in between your poetry and sculpture. Could you speak on how you situate drawing in your practice?

SS: Drawing is one of the few spaces I feel — it’s like I can actually do it in public. It represents or embodies stuff that I didn’t allow myself to do in high school because I was essentially trying to flee my family so I was working at every second to get a full ride somewhere. And I just didn’t let myself doodle, or listen to music, or cut class, or do anything to relax. And then I got to college and I was like, fuck everything, and then drawing came in and it was very therapeutic. I don’t actually draw in public, since it attracts a lot of attention, but it’s something that I do in semi-public spaces where I kind of have a knowledge of people in the room. But it’s not something I do in my studio when I’m completely by myself. So it’s got this flexibility and is directly in between how I write and how I make sculpture, which is nice.

** As you speak about the slippage between the mediums, and the kind of public-private boundary, it seems to me like a lot of your work is about the violence of visibility. Which a lot of people misread as being related to fashion or fads or something, as opposed to being about these like circulations of tropes and the ways this affect our navigation of the world as targets of these tropes. Of course there’s room for sides, but I see more of an analysis of violence in your work than one about fashion or anything. Does that ring true? If so, how does it relate to your history as a community organizer?

SS: I don’t have any nostalgia. When people read a nostalgia into what I’m doing, I’m just like, what do you mean? At what point was I ever able to don a cute, silky nightgown and watch some Disney thing and not just be kind of the fucked up… I don’t know, childhood was really fucked up. I mean for a lot of people, it’s fucked up. When people read like, oh, you’re just so nostalgic, you’re using things that look like they’re from the 90s, or like from here and you’re warping them. How nice, and they’re all so pretty, and it’s lace—It gets me mad. So when I was organizing in high school, in a lot of organizations it was very much about this culture of respectability politics, because most of it was for black and brown queer people and GNC people and it’s hard to find access without assimilating to legibility.

But at the same time working within organizations of boys and men of color in particular, it was very much about being suited up and passing — passing as educated, as a man, as non-delinquent, as “one of the good ones.” Of course, they were doing this because they were dependent on public funding, but given their youth focus it’s quite damaging to expect this kind of assimilation and enforce it in various violent ways.

About the sculptures in particular, I’m not working with nostalgia, I’m working with the messaging around what should be, and what is peoples’ right to nostalgia. It’s just this total wiping of how dehumanized I felt as a kid. I realized this really early on in high school that the way that I was choosing to present in public at the point where I realized I was GNC was also in a way directly related to how I was attempting to obscure my class position while I was doing all of this work on behalf of black and brown queer kids. Because I would have to meet with foundation types, NPR types who wanted a certain image.

** Right, and there’s a kind of martyrdom there too. If you’re butching it up and dumbing it down, you can fill that respectable position and that organizer role, as well.

SS: Yeah, because at the end of the day, what was required of me silently throughout all of this work, was essentially, I just had to look like a mestizo nationalist. And that’s very much what I came to New York looking like. And it worked—I was in these organizations and was respected and as soon as I flipped the switch to even dressing a little bit differently, I just had people that I used to organize with being like, why aren’t you respecting your indigeneity? Why are removing parts of your facial hair? And when I changed my pronouns, I just got all kinds of shit from people that I used to work with that were just trying to fuck me on the low but I was just too femme for them and other shit. And now they’re openly queer, and it makes me laugh.

** Because they’re a fucking joke.

SS: Yeah, it’s a fucking joke. But in regards to how they interact with how I present sculpture work now—Yeah, I hate the idea of childhood. I’m mad that I didn’t get to participate, and it’s because there wasn’t anything to participate in. It was reserved for middle-, upper-class white kids, and still is in the way that it plays out. I guess I can’t ever judge mostly cis peoples’, and then especially in a lot of people’s cases, that whole American dream. Dying your hair blonde and really kind of clinging to—I don’t know, it’s just all so violent. I guess I’m just trying to make—I’m not trying to make fun of it,. I’m just really mad.

** I think you recognize that you’re trying to crucify it, but out of maybe a desire for it, or something. Or the way that respectability is coming from both the top and from the bottom, from your peers who see your gender as somehow ‘white.’

SS: Yeah, and it’s really sad. Because I do desire it. I remember watching movies like Hocus Pocus and other things as a kid and really wishing that I had a nuclear family and a brick house with a graveyard in the neighborhood. And people even knowing about their families generations back, and having access to that. And having a lineage, or a lineage that wasn’t obscured by history’s violence—I don’t know, there’s something about, you can’t claim the dead when they were never considered part of life in the first place, that I kind of hope that over time the sculpture works that I’m making become markers of people that were never there. When I make work out of cute things for kids, this is the ghost-kid that was never there and just kind of dissociating into oblivion with whatever they could find and then leaving their shit between VHS tapes because they didn’t want to take a break from dissociating.

** It’s funny too to me how those things go hand-in-hand so consistently. Especially thinking about imposter syndrome and respectability rules, there’s a necessary level of dissociation and disidentification that goes into being part of that, out of a survival instinct maybe, as away of like protecting oneself from one’s violent complicity in these systems, in desiring these white ideals. And yet the flip side of, there’s the drive, like the sense of actualization or agency that comes from being in community. Could you speak to this?

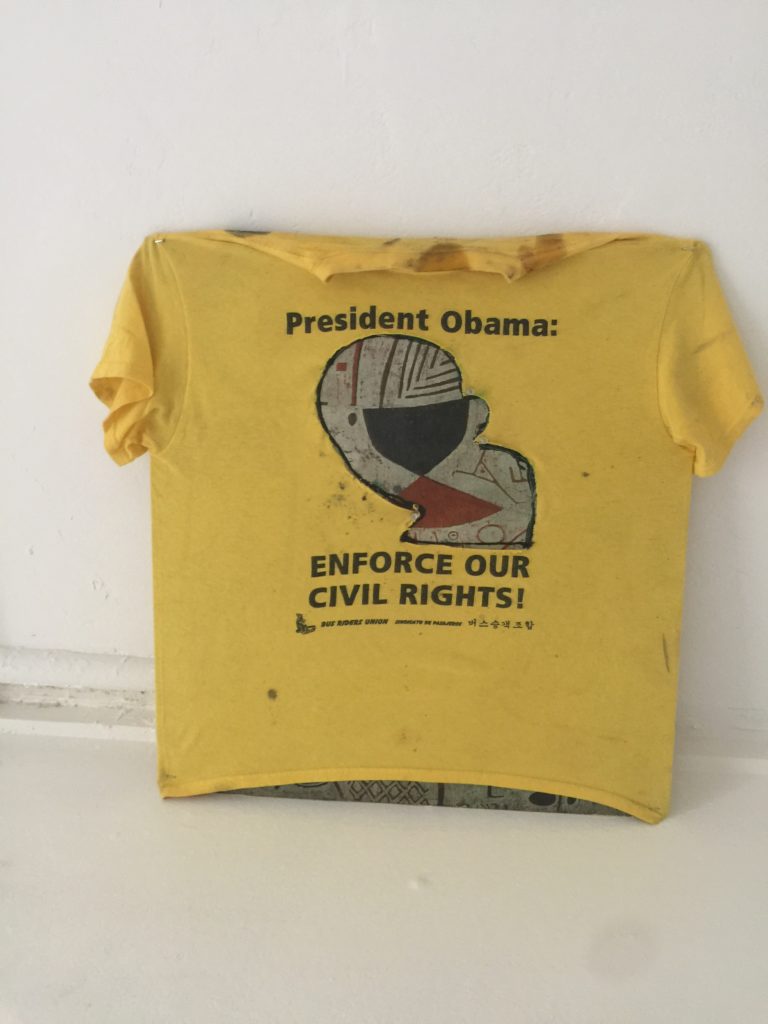

SS: Organizing is really where I first found my agency. I loved working with other GNC people my age. Within a lot of these positions there would always be group art-making components to every one of these discussions. It was just kind of inherently creative or speculative: what does a world without cops look like? How do we work to push them off-campus and end the trend of schools bringing in the LAPD to take care of minor things like truancy etc when counselors should be doing that work? So we would have this lengthy discussion about the policy behind that, and how to challenge it over time. Then at the end of our discussion we’d sometimes make a group collage visualizing the conversation. It would be this huge wall scroll imagining, say, what a community-oriented school would actually look like. And that would be with markers and yarn, and again most of these kids were my age, so 14 – 17. At that time, I was still sharing space with family members. My mom hated clutter so I couldn’t put anything up on the walls; my time to be creative was usually in these very policy-focused organizing spaces.

But my gender nonconformity was still being constricted in my presentation in these spaces a lot of the time, partly due to occupying leadership and facilitation roles. I just couldn’t present authentically in certain spaces, because I knew too many people and could tell that they were having visceral reactions to engaging with me as an openly GNC person. And that just hurt coming from my folks, so it was easier to exist in explicitly queer spaces. Then college came. I finally had a language and control over how I wanted to put stuff on my walls. Throughout my life I was hoarding all the time and then took a lot of that stuff to college. But I didn’t start making physical things until junior year. At that point, the first things that I made other than the drawings, the things that I gonna show to people actively, were so refined. That aesthetically felt very much like when I was participating in these workshops and having this strict role to fill. So that’s when I started playing around with a messier aesthetic, and engaging the hoarded stuff in a more embodied or less respectable way, at least to me. Thus me taking a shit on everything! ***

The Prick up your Ears group exhibition is on at Karma LA, running August 5 to September 9, 2017.