Although it would seem strange, the question of audio fidelity comes with ethical baggage. The word wasn’t used to describe truthful-seeming sound reproduction until 1878, and to this day it homophonically evokes ideological duty, whether to a monogamous relationship (boring!), nation state, or job. Canadian composer Kara-Lis Coverdale has consistently disavowed the traditional demands of audio fidelity — the ‘reality’ her sounds would be faithful to always remains an unstable reference point. Those listeners looking to her new record Grafts, released via Boomkat on April 27, for evidence of the Latin fidelitatem (nominative fidelitas), meaning “faithfulness, adherence, trustiness” will not find it.

In her 2010 Masters thesis, ‘Sound, Rhetoric, and the Fallacy of Fidelity in Recorded Popular Music,’ Coverdale problematizes the idea of ‘realism’ connoted by recorded music, arguing that sonic ‘realness’ is an ideologically — and inorganically — constructed notion. Proceeding from this conclusion, Grafts is an object lesson in the way timbre as a communicative apparatus rhetoric can be strategically manipulated. As the composer explained in a since-deleted note accompanying the piece on SoundCloud, it is the result of an interlocking set of translations across mediums and file formats, of texts within texts. The production process began with a technique initially developed on Coverdale’s 2010 album A 480, whereby digitized sounds of the human voice were “disembodied, disfigured, and displaced” from any resemblance to their source. From there, each hacked tone was “split up to four ways, then re-pitched and re-woven through a back-and-forth grafting procedure of layering and securing on a four-channel processor.” Next, “interdependent layers of shelved frequencies (rather than equal tempered pitches) [were stacked] to produce frequentially-terraced composites.”

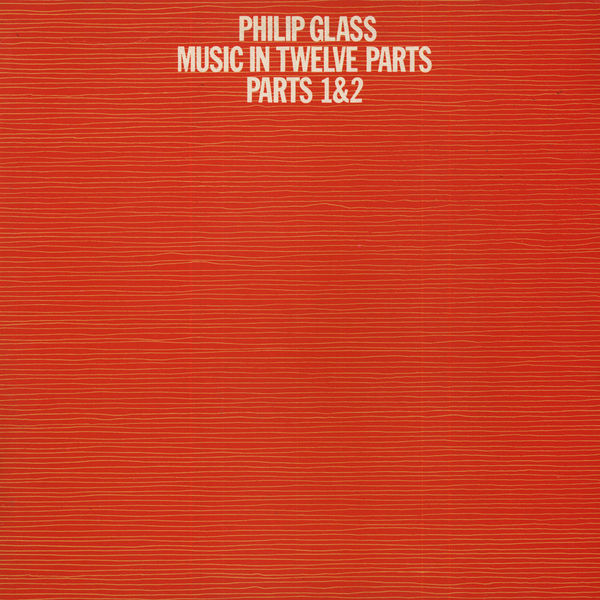

Even without all this technical background information, there’s something about the approach to arrangement on Coverdale’s new album that asks to be diagrammed, more so than anything she’s produced to date. This is in part due to the 22-minute work’s geometrical nature: tessellating motifs gather momentum, sustain, and diffuse in three semi-linear movements held together by a continuous flow. Atomized sounds come together in strange affinities — an exhausted organ pad washes over glitched expressivity here, tones disjointedly echo one another in receded pockets of the mix there. Along with its addition-and-subtraction melodic progression, Grafts’ mathematical structure resembles the repetitive, slowly-modulating compositional approach developed by the New York minimalist school. Although Grafts is definitely more reminiscent of Steve Reich than it is Philip Glass, Sol Lewitt’s cover artwork for the latter’s 1976 album Music In Twelve Parts – Parts 1 & 2 offers a productive point of departure for situating Coverdale’s work in diagrammatic terms.

Lewitt and Glass’ work in this instance is hand-drawn in clear lines, suggestive of a distinctly Fordist mode of production — human, but learning to hybridize with automated technological processes. When effective, the New York school’s works — such as Reich’s Drumming — ease the listener into a state of transcendence, composed as if to draw forth a resonant, ‘pure’ idea or feeling, elaborated with crystalline clarity. We can still see evidence of a traditional approach to audio fidelity there. In marked contrast, the emotional tenor of Grafts is opaque, polysemous, and folded into itself. The experience of listening is like being subcutaneously sucked into an alien swarm. Grafts’ emotional narrative is cohesive on the macro level, but on the micro level harmony and dissonance are harder to locate, enacted as they are in superimposed, interjecting stacks. Their arrangement is the product of innumerable contingent functions taking place behind the scenes.

Is there a clearer diagram than what Coverdale offers with the title — a multiplicity of grafts, winding, twisting, and “frequentially terranced?” Although the production process has created a concrete, finished work, Grafts still seems to be in limbo, on the verge of falling apart due to so much calculated chaos. Catchy melodies learn to live with and against their own auto-regurgitating churn. “Destabilization is inevitable and facilitation of brave reconfiguration spawns a seed,” writes the composer in the Grafts program notes. “Who is your seed maker? I only know I have more limbs than I can count and I am far beyond the edges of myself.” Grafting is the surgical process involving the transplantation of skin from what part of the body to another. Skin here can mean many things, it seems — epidermis is just the start. There’s also a horticultural process of grafting, where the vascular tissues of different plants are physically conjoined so that they produce a cumulative hybrid organism with selectively cultivated attributes. The important thing on this LP is that the transplant/suture process has been so intense that it’s impossible to quantitatively enumerate; it’s not possible to contain in any definitive sense. Lightheadedness at the prospect of differentiating root and stem, limb, or flower qualities in turn gets mixed up with subtly aggro key changes and disconsolate melody-cycles. “A gut has its own intelligence,” writes theorist Sara Ahmed in her recent book Living A Feminist Life; the listening gut sounds a certain eerie alarm, with the fidelity-void on the Grafts horizon. It’s not clear who or what presides over the operating table.**

Kara-Lis Coverdale’s Grafts was released via Boomkat on April 27, 2017.