“Since there is no equivocal definition of life, most current definitions are descriptive,” reads Hannah Black‘s ‘Beginning, End, None’ three-channel film installation, a triptych of audio-video collage exploring what it means to be alive through the ambivalent idea of the ‘cell.’ The word can “denote both a biological and a prison cell,” points out the press release for the Berlin- and New York-based artist’s most recent Small Room solo exhibition, running at Vienna’s mumok from March 16 to June 18.

The pronouncement lends itself to the questionable tendency by many to draw parallels between biology and sociology, constructing systems of thought and creating categories with the precision of a taxonomist: “One of the major problems that has happened in the past is that people have been too quick to draw political conclusions from biological ideas,” says a disembodied voice in ‘Beginning, End, None (Beginning).’

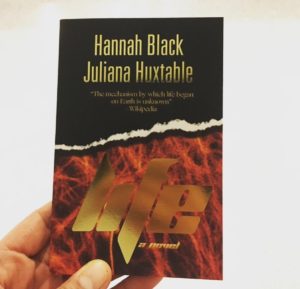

Accompanying the show — strewn with floating latex sculptures resembling human skin and dominated by the ghostly video work — is a book called Life, written in collaboration with artist Juliana Huxtable and designed by Soraya Lutangu. In it, two risk assessment analysts and former lovers called Hannah and Juliana, write to each other about their relationship and the meaning of life against the backdrop of the end of the world: “No one is getting out of life alive, and you can’t handle it.”

The text was written via email, the two artists responding to each other between Berlin, New York and in transit as if they were the characters they represented. “I imagined a love story,” says Black via email about the approach to writing Life with Huxtable, “she pushed back on that, and then I tried to charm her. All that happened as a writing process and in the narrative too, where her character starts out a little contemptuous of me and then softens, I think, though that might be a partisan reading.” Partisanship, or at least interpreting information with a certain bias is where a book like Life, and also the themes of the Small Room exhibition, ultimately linger. Analogy as an ideological claim (in comparing the natural state of a cell to the manufactured assertion of the factory, for example) and the ambiguity of defining a thing called ‘life’ (biological cells are alive but they do not have a heartbeat) converge at a point of perplexity.

**The press release talks a little about your work “interweaving the personal into these theoretical ideas,” there’s a dialogue between yourself and Juliana from two locations, Berlin and New York, two places you are/have been based. Is that dialogue informed by those two experiences?

Hannah Black: We were both travelling a lot of the time, which is part of professional art life, but I have an idea that Juliana handles it better. For me, it makes me feel like the stricken man in Arthur Miller’s drama classroom classic The Death of a Salesman. You can see in the text that it is partly written in transit, I think, sometimes explicitly and sometimes as a matter of tone, a certain breathlessness, like someone running, and the characters are moving too: they pass through cities and airports, they move towards the edge of the end of the world. I wrote one passage, the part where my character encounters Mike Precipiz, on a plane and in the taxi home in a kind of trance. I’m so proud of it, but as if it’s something unexpectedly valuable I picked up in the street, like it’s not quite mine, which might be the reward of working with someone else, or might just be a thing about writing.

The opening part of the book, where I describe my character as kind of retired in Berlin, washed up in Berlin, does reflect something of how I feel sometimes, when I’m there. The parties and the familiar people can feel like lights glowing in fog, the fog of some kind of city-specific loneliness, and also the literal darkness and silence of the streets contributes to this feeling of everything being swallowed. My impression of the city is that it’s like a throat, and I’m writing to you now from New York, where things move up into the mouth, but I understand that when we talk about cities we’re only talking about ourselves there. I think Juliana would feel differently about these places, and I can’t speak for her. Or, on a bigger level, maybe the sense of Germany as the last remnant of an era of social democratic confidence and unity contributes to this island feeling.

**There appears some sort of discussion in Life about history + its ultimate disavowal of its existence, is that something Small Room also tackles?

HB: My friend Tiona McClodden recently curated a retrospective of Julius Eastman’s work in Philadelphia, and she told me about how hard it was to assemble all the material. Some of his scores have just gone missing completely. For one composition, the only extant copy of the score was found in a magazine that happened to use it as a kind of textural design thing superimposed on an image. I think what this story made me think about is that history is an accident as much as life is, an accident shaped by both malign and loving intentions.

**I say this, particularly in relation to the book, which takes its title from the Wikipedia entry. On reading its crowdsourced description on what constitutes ‘life,’ it becomes harder to grasp, like some kind of blackboxing effect. Is this something that drew you to this title in the first place?

HB: Yes! I find in a concept like ‘life’ a really attractive combination of abstraction and concretion. The theorist Yve Lomax, who taught on my MFA at Goldsmiths, was really interested in the idea of the example: she writes that the example “stretches the distinction between the universal and the particular, the general and the individual; it is, characteristically, neither one nor the other.” A living person, you, or me, or anyone, is an example of what life can be, but our exemplary being is mostly irrelevant to the question of what life is.

Black box is an interesting term that you used here, because a black box is something that records a disaster, and I guess that was the impulse of the book, which is part of a kind of feeling, both grandiose and sad, that we all might be in the process of recording the end of a world.

I want to also say that I love Wikipedia, or at least I did until someone made me a Wikipedia entry and I experienced with terrible directness the many problems of common knowledge, for example that it’s often untrue.

**In Dark Pool Party (and maybe Not You), there’s this idea of the “abolition of the analogy.” As a writer that’s a difficult mandate to uphold. Maybe this doesn’t relate so much to this exhibition but I’m curious to know what you mean by analogy, and how you either do or don’t enforce it in your own work…

HB: This was an idea I got from what some people call ‘Twitter university,’ i.e. the ongoing political education happening online in the form of arguments and discussion and so on, and also from black theorists such as Frank Wilderson, who I started reading very fervently towards the end of my MFA in 2013. I was staying at my friend Anna Zett’s magical place near Leipzig with a bunch of people and we were stoned and lying on the grass in the sunshine and joking about “reparations for childhood.” As the only person with phone signal, I was detailed to tweet this thought, which seemed important under the hazy conditions, but I stopped myself halfway through, and someone said, kind of mockingly, something about me having momentarily forgotten my audience. And I was stung, because I often get it twisted and think that performativity is a form of lying, and I said something like, ‘It’s not that, it’s just that in the countryside you forget the war on analogy!’

This needs context: the thing is, reparations are presently primarily attached to the question of the working-through of transatlantic slavery and its aftermath, this is very well known, so the concept can’t be lifted away from this question and reapplied to another category, that of children, without considering what this does. This often comes up in relation to slavery, which gets used as an analogy a lot. This occurs often in critiques of white feminism: people notice that white feminists were somehow able to conceive of wives as in the situation of slaves, without thinking about the factual existence of enslaved women. If you begin with an incoherent or thoughtless position like this, of course you have trouble further along the line, or you’re confused when people that you see as an example of your category, as women just like you, kind of reject or escape the category. Antipathy to careless political uses of analogy often gets interpreted kind of his-terically within a white bourgeois or white masculinist perspective as a ban on thought, but it’s a prompt to thought, an offer to thought.

Of course, completely avoiding analogy is impossible, but it’s interesting to see what happens when you expose political comparison to a kind of mathematical rigour. I think that’s also what Wilderson is trying to do with his work on solidarity, which insists that you can’t start by assuming class cohesion between different race/gender positions, especially if cohesion is part of what you’re fighting for.

**…I’m also interested in how that translates, if at all, to Small Room and Life because both seem laden with analogy, correct me if I’m wrong…

HB: The show continues my attempt to think critically about analogy. It was originally inspired by an analogy that is common in high school biology teaching, or popular science: the biological cell as a factory. I wanted to look at this skeptically, as it compares a historical and social entity — the factory — with a transhistorical, natural one — the cell. In doing so, it makes an ideological claim: naturalises the factory, commodifies the cell. The word cell gives the exhibition its title; of course it’s the same word as the prison cell. In the end I couldn’t do much with the analogy apart from notice it. The video kind of hovers in between factory, prison and highly technologically mediated images of cells. Maybe it’s true that the violence of capitalism is echoed even at the structural level of our cells, and certainly it now reaches into the cellular structure of the world through pollution, but I prefer to believe in something else: perhaps that the cells are closer to how they seem in the unannotated lab images, spectral entities, uninterpretable without the right insight. This is the material we are all working with.

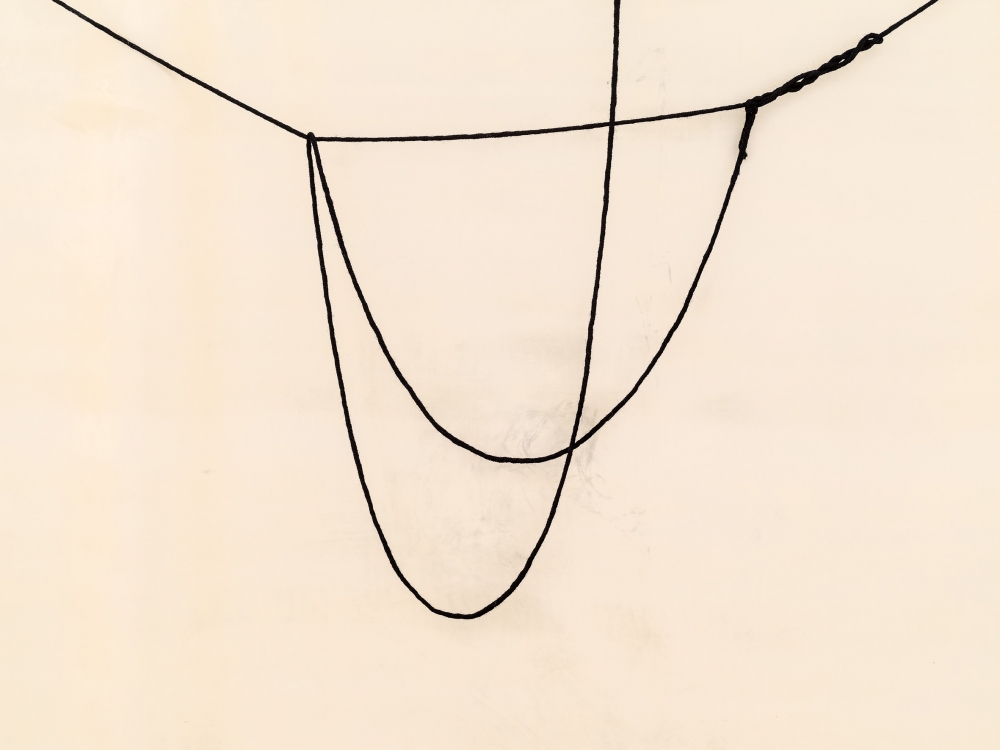

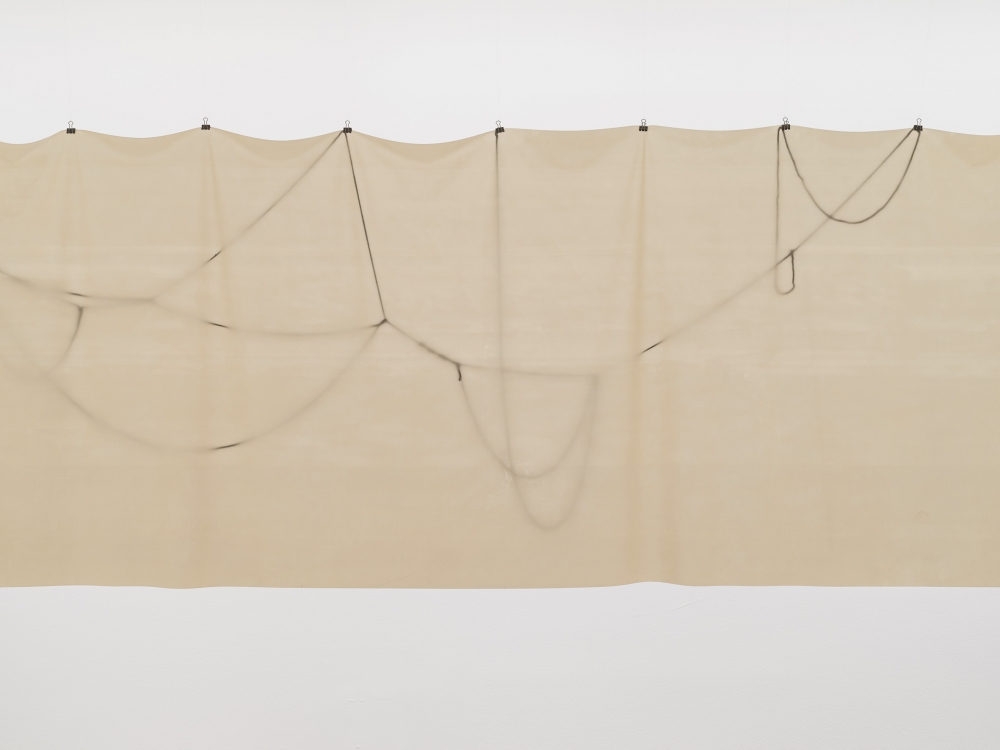

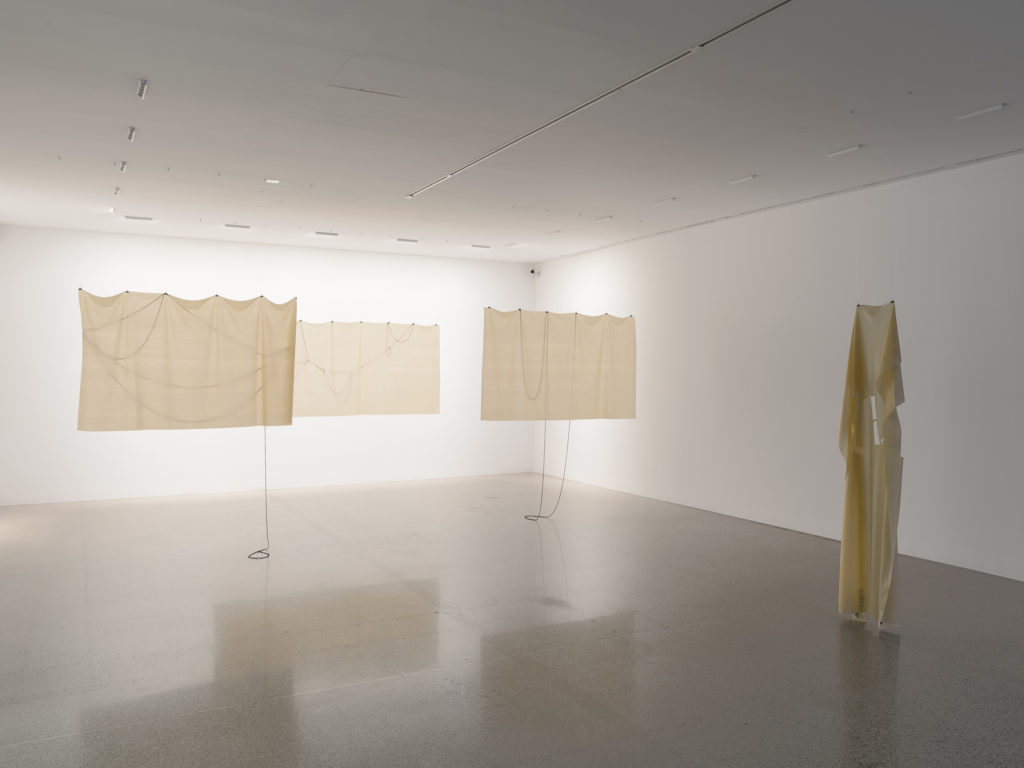

Formally, the installation is structured around an analogy between surfaces. There is a mirroring effect across the space of the gallery, with the three latex works called ‘Membrane 1, 2, and 3’ facing the three screens of the video installation. The phrase that the latex pieces take up from the video is from a biology textbook: “No life without a membrane of some kind is known.” Then on the floor towards the ad display at the back of the room there’s a work called ‘Temporary,’ which is a scratched-up mess of temporary tattoos stuck on the floor, so that the floor is also proposed as a kind of membrane or skin. As part of the process of making the show, I talked to people with scientific expertise to help me understand the material I was working with — Adriel Arsenault and Shay Akil McLean — and I learned some extremely basic facts that I had never grasped at school and was kind of amazed by, for example the structure of the cell membrane, this very thin layer between life and nothing. I have in my notes something helpful that Adriel said: “It seems very magical and designed and like that it ‘knows’ how to be a skin, but it’s just this very basic automatic response.”

I wanted to maybe complicate the simplicity of a question of difference that stays on the surface of what Fanon calls epidermalization, that stays in a biological concept of difference, and think about how difference and universality co-constitute each other. In a way, the animalized or biologized other, whether that’s an idea of blackness or femininity or whatever, is seen as belonging more to the abstract category ‘Life’ than to the singularity that could exemplify life. We can be life, but we can’t be an example of it: this is just from one perhaps too-abstract point of view. But I don’t know how to do anything; the work is just this very basic automatic response. I made the exhibition in a kind of frenzied period of my life, a lot of falling and getting over, a lot of happy and unhappy accidents, a time when I understood some uncomfortable things about myself. A series of titles in the video say, “I did so much wrong / And can’t forgive myself / But.” Living is its own imperative, no matter how I feel about that. A membrane reveals and shields, limits and makes possible. The presence of the ad display work, with its very clumsy title — ‘Movement trajectories of kinesin-cargo complexes can be seen as white paths’ — was also meant to indicate how all this is being worked out and through under conditions of commodification, which produces all sorts of difficult universalities, difficult differences. I guess this is all an analogy but after all this time I’m still not really sure how an artwork relates to analogy. I think an artwork’s saving grace, if it has one, is that it’s also just dumbly and materially itself, and kind of resists becoming either an analogy or an example of anything.**