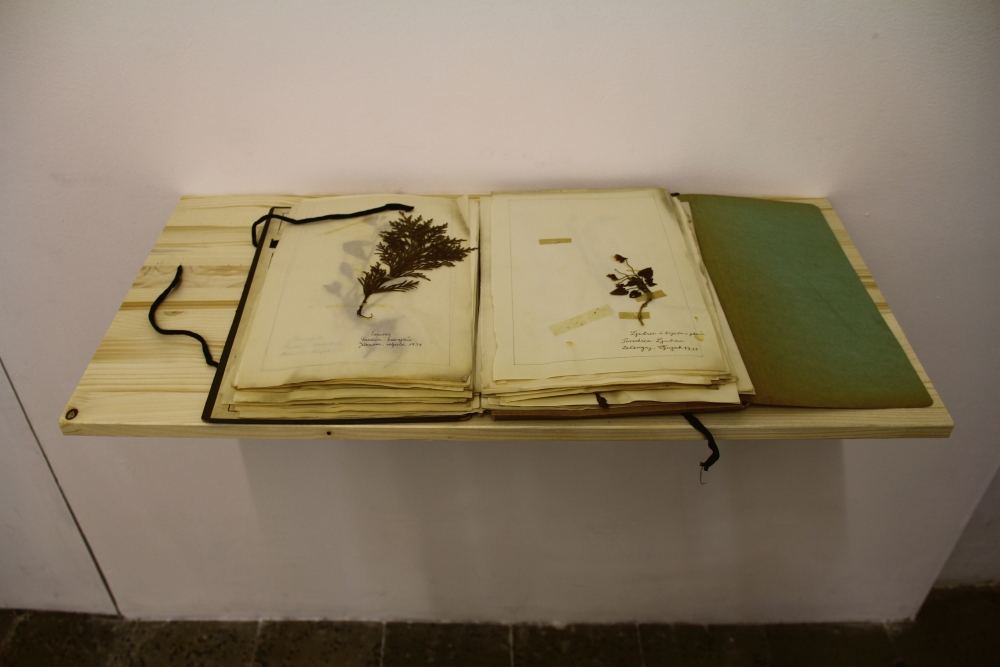

A single potted tree of the same height as artist Pep Vidal is the only organic addition at the front entrance of Barcelona’s Halfhouse. It’s part of his Jardín Botanico exhibition, open December 17 to March 18, in an artist-run space in the hillside neighbourhood of Vallvidrera. Along with pre-existing plants that will continue to grow throughout the exhibition, this meaningful insertion will track the time of divergence from the initial action. The gesture of this single introduction represents Vidal as an imported player in the garden, just like a new species or purchased flowerpot. With a PhD in physics from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Vidal is interested in the mathematical systems which never align with the cultivation and life of organic structures. As a co-inhabitant of the yard, rather than its creator or manipulator, this role assumes a position which acknowledges nature’s causal determination in the final project, as well as a personal involvement of living under the same laws of nature. As time passes and the tree grows taller than the artist, the intervention in the plot will also change, shift, and eventually become overgrown. As winter becomes spring, the plant labels will be ingested by their environment, a living plastiglomerate.

In a recent article on this Anthropocene object, Professor Kirsty Robertson investigates the appearance of natural rocks formed from pieces of plastic debris deposited in the ocean. These plastiglomerates develop through pressure and heat in natural processes, but the man-made components are uncannily appropriated by nature in new ways. They show up on beaches — transition spaces between land and ocean — as what she calls ‘marginalia’ from tidal streams and currents. Meanwhile, traditional botanical gardens, which preserve and study living organisms by adjoining them to categorical labels, inform our viewing of the plant as belonging to a system of knowledge. When untended, vegetation has a tendency to take over its habitat, to break through glasshouses, and appropriate its surroundings into itself, absorbing the plastic, pots, and architecture into new forms. Like the ocean marginalia, plantlife also consumes forgotten human objects. The purpose of the botanical garden was never about preserving plants without humanity, but about bringing them into human understanding. Consequently, a phenomenon in physics known as the ‘observer effect’ describes the difficulty in taking certain measurements without human intervention influencing the result as a matter of the observational procedure.

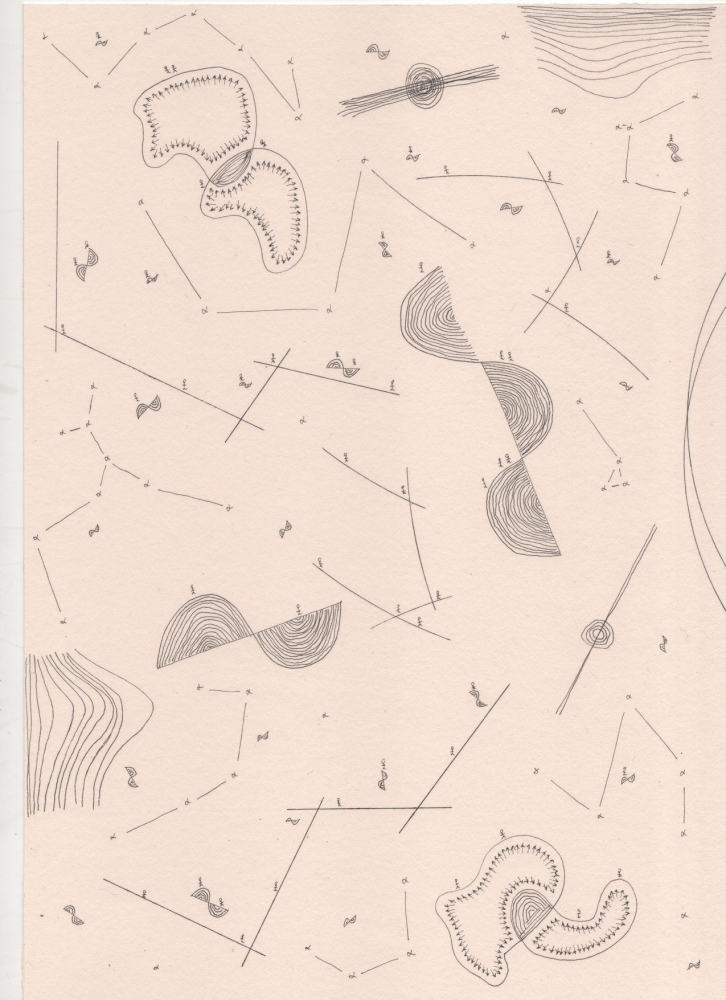

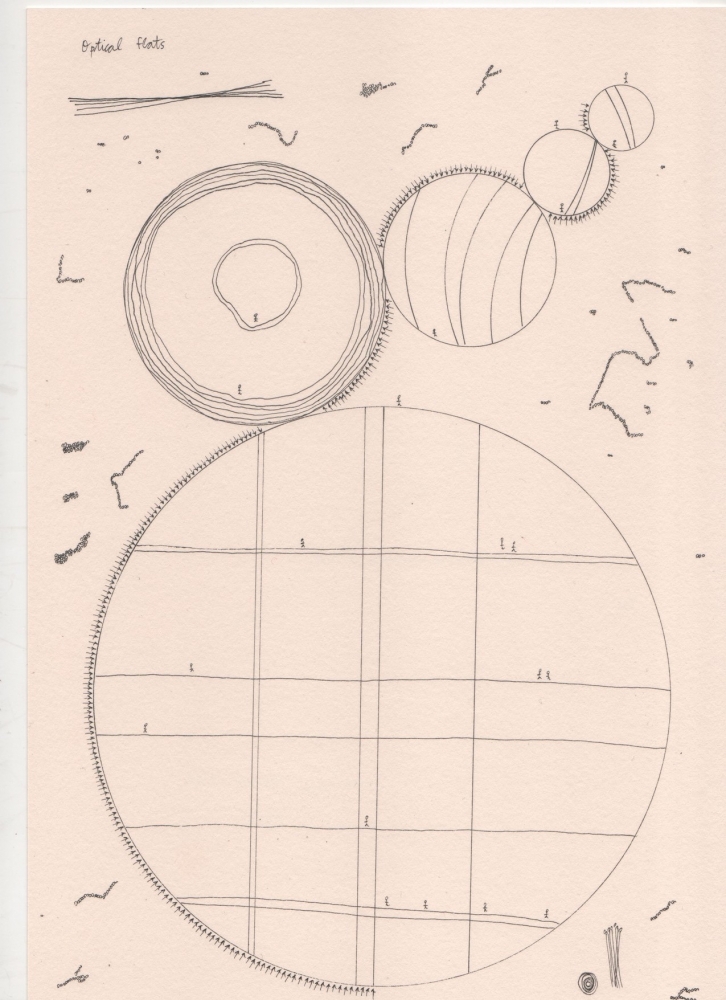

The main work in Jardín Botanico is arranged alongside each sprout of vegetation in the entrance as if for scientific study. Rather than importing living organisms to the exhibition, Vidal has categorized the existing trees, bushes, and weeds into an organisation that plays with methodological observation and its failures. Tall signs classify species into their Latin names, while short ones contain drawings inspired by a plant nearby.

In Vidal’s inverse botanical garden, the interventions react to the conditions of the garden itself and propose a format of co-creation between the artist and the environment by including weeds and uninvited intruders brought into the plot by forgotten or floating seeds. On first opening the door, a couple of meter-long spirit level rulers sit on bushes, a tree, and the roof of a shed. Each measuring tool bubble represents a constant statistic, gauging different rates of growth and instability. The bubble on a short shrub oscillates constantly, not only indicating its development but also the elasticity of its sprigs. Two thick tree branches hold a device which moves at an invisible rate, calculating the divergence of the two limbs. Each of the three levels record and react to their environment while simultaneously influencing the life of the plant. Through the observer effect, the weight and position of the instrument encourages behaviours and patterns on the twigs and foliage.

In philosopher and theorist Michel Foucault’s ‘Of Other Spaces,’ the Persian garden is used as an example of a Heterotopia. Utopia exists in virtual space, while heterotopias exist in real space but represent an incompatible spatial multiplicity. A precursor to modern botany, the Persian garden existed in square form and represented the entire world based on its four corners and centre. Modern scientific categorizations of plants intend to bring together biomes, which do not fit geographically through the juxtaposition of exterior parks and glasshouses. The heterotopia created in Vidal’s project exposes a warped space through the visible insertion of observation. The Jardín Botanico becomes its own cosmos, centred around the absurd network and relationship between humanity and other species. Its location at Halfhouse creates a context of the urban city limit and makes the project possible, where the residential buildings start to recede from the street behind their own front yards. Vidal’s exhibition is located on the boundary between the urban centre and the periphery in an urban heterotopic garden, edified but green. If botanical categorisation is a reference to the representation of all plant-life, the location of Halfhouse is the urban version of Robertson’s ocean plastiglomerate beach ‘marginalia,’ a footnote to the urban essay.**