Penny Rafferty is founder of Ying Colosseum, alongside key players Silas Parry, Kyle Joseph and Alex Chalmers. The artist and writer marks the end of the 13 month-long programme of site-specific ‘happenings’, running from 2015 to 2016, with a reflection on its strengths and weaknesses:

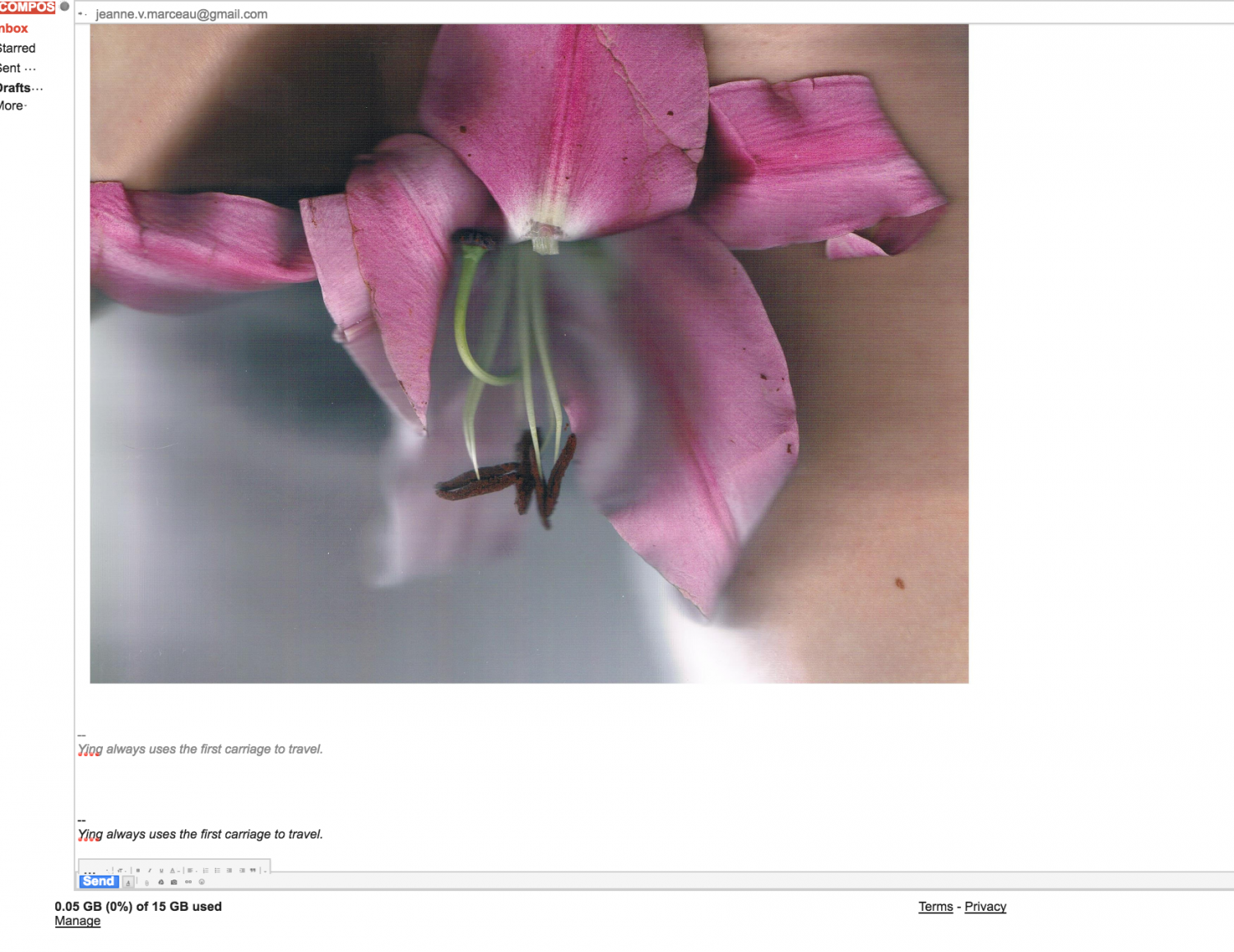

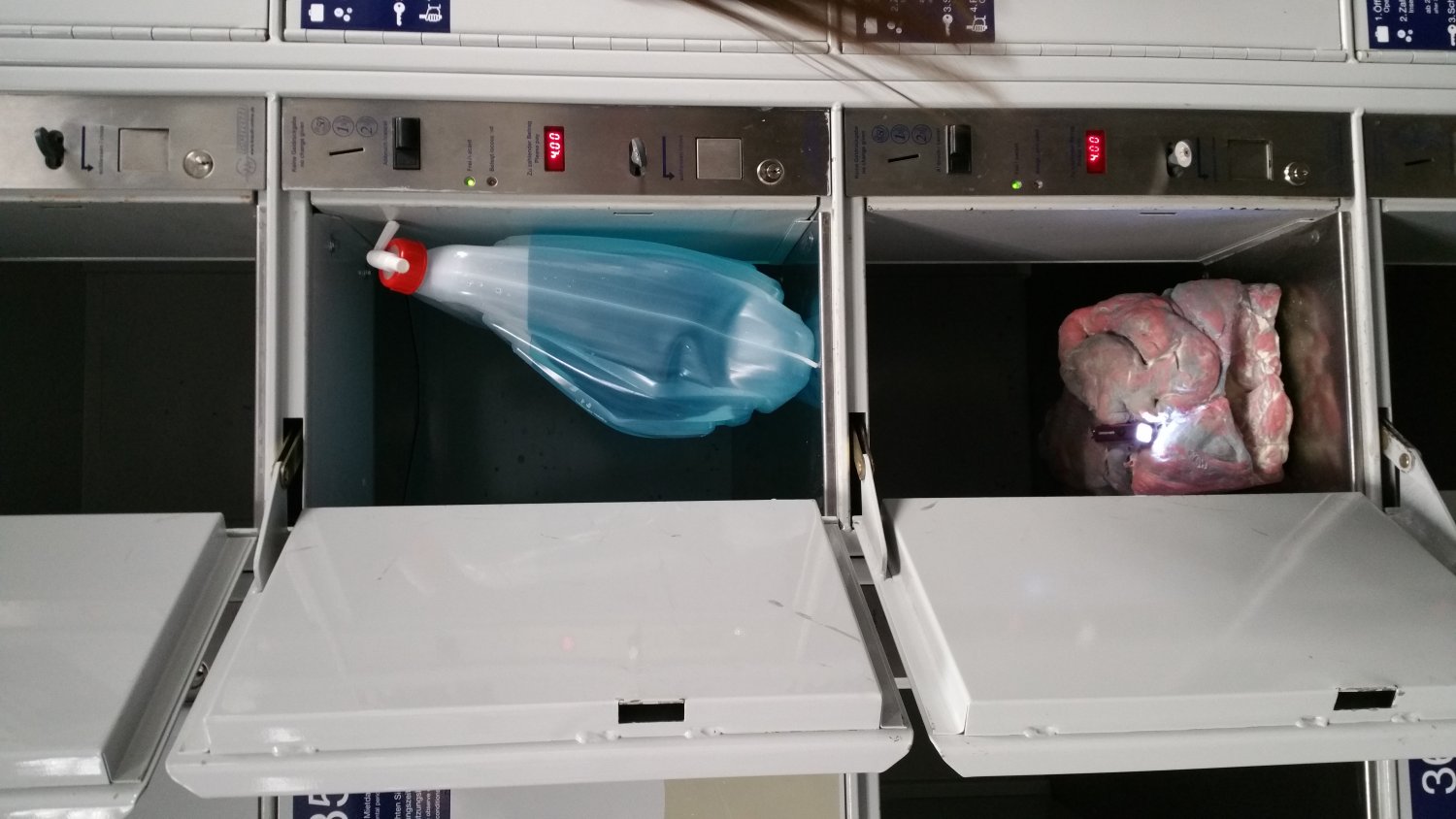

Every last Sunday of every month, for 13 volumes since December 2015, the shape-shifting Ying Colosseum collective had been descending on “sites of interest” to stage art happenings across Berlin. Ying’s focus has always been at odds with the art world. Enabling artists to show their work in a Turkish bakery, a supermarket car park and at the centre of the German city’s infamous May 1 political demonstration, it has always attempted to incorporate a horizontal viewing economy for the shared optical nerve of the ever-expanding mass of young, Berlin-based and visiting artists. However, on November 27, 2016, Ying staged its so-called “final offering” inside its own email account, yingcolosseum@gmail.com, giving out the password to artists and viewers alike. This was at the heart of its network, where all announcements were passed between its participants and their nodes over the course of Ying’s 13-month life-cycle.

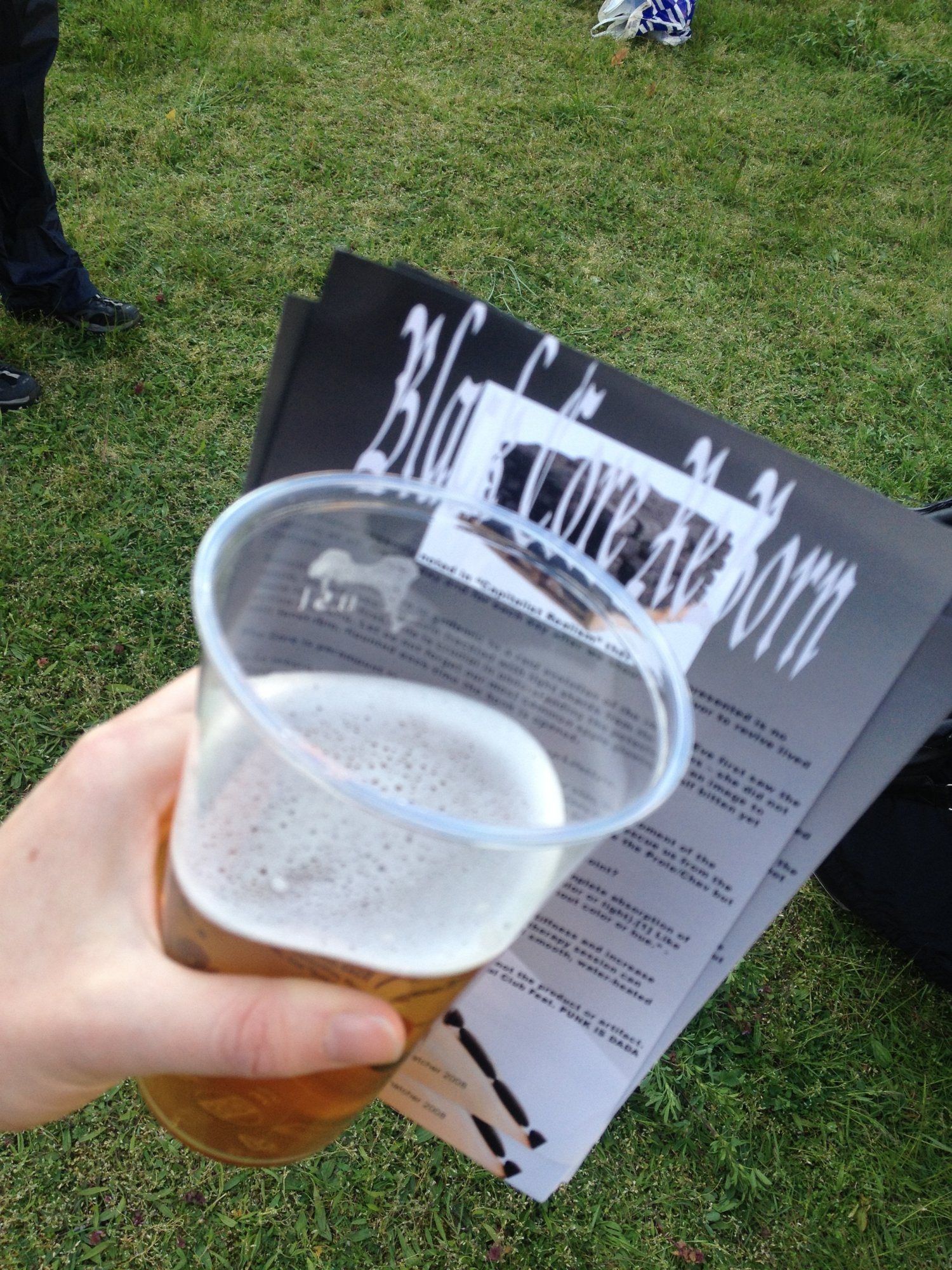

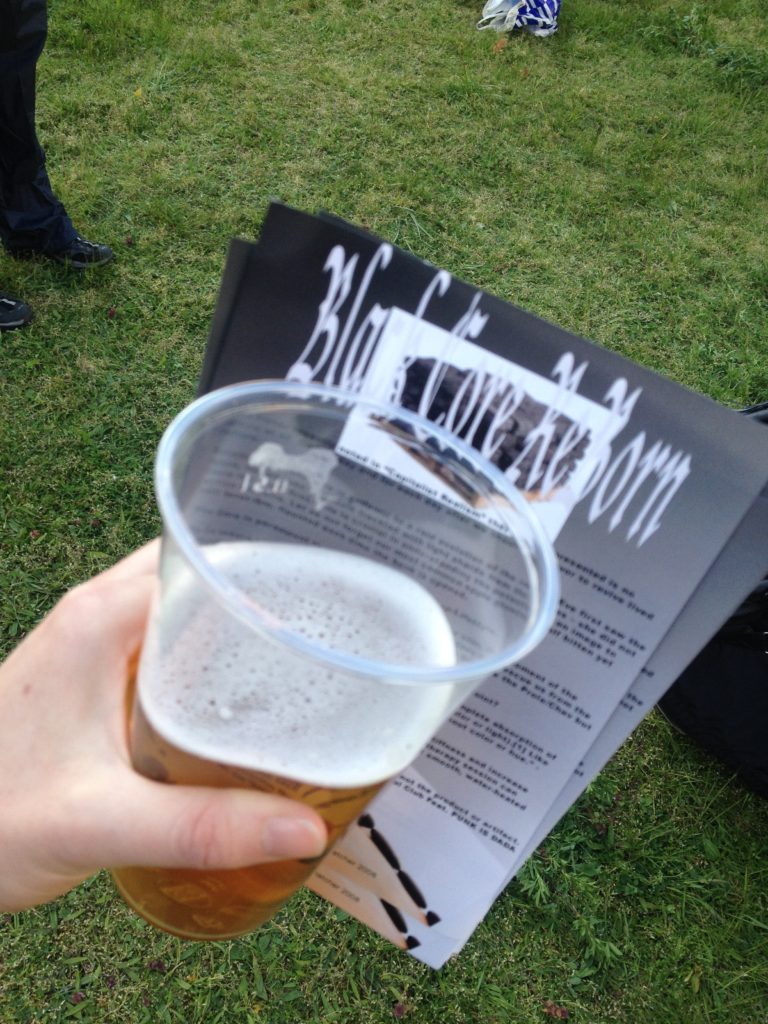

Ying Colosseum acted as an algorithm, it had a set of rules and components that manifested in a final outcome, but unlike the associated digital code, it had set spaces for human error by way of eschewing curation in favour of mass participation. It was created as a critical approach to the problems faced by present-day cultural platforms and workers who lack space and funds for experimentation. It used accessible communication technology available online — such as a Facebook events, or Instagram hashtags, or email invites — to transfer art information from viewer-to-viewer, enabling engagement with the work and community. Ying hacked away at the traditions and tools of the artist by eschewing press releases, floor plans, install dates and curated legal space. In doing so, it opened and installed exhibitions on top of a post-industrial bridge, inside a Korean restaurant and in a Renaissance-designed Prussian park, creating an anonymous culture of anarchy comparable to the Situationists playing Pokemon Go. Artists would cautiously appear on site, lugging IKEA bags (an up-and-coming artwork transporter of choice) or apologetically announcing they were unsure of the location. Then the negotiations would begin. With only 15 minutes before commencing, there is no curator, no authority to direct installs or programme line-ups for performers. Together, a conversation begins and a beer is opened, gaffer tape is found and Ying Colosseum opens.

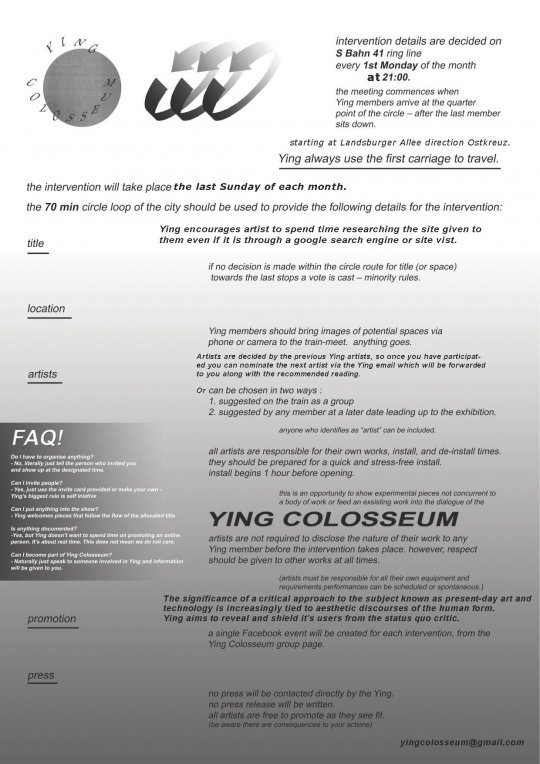

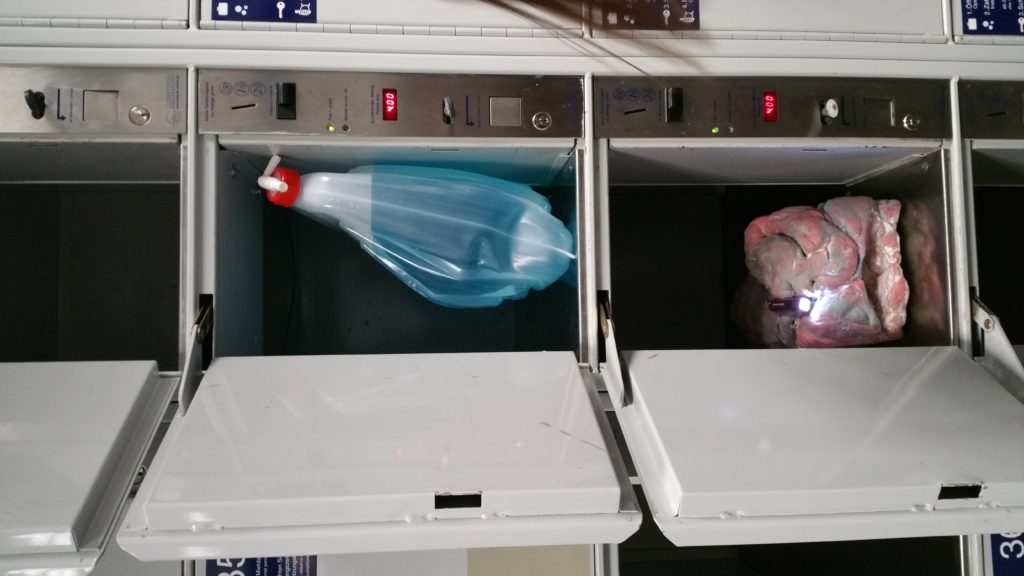

Each Ying event was decided by the same systematic unit. Whoever was interested or was invited by previous participants met at 21:00 hours on the first Monday of each month at Landsburger Allee Station. They boarded the Ringbahn subway route, which traces a looping route around Berlin — one full circle. Always travelling in the front carriage, participants decided on the site of the next Ying Colosseum gathering by presenting mobile phones photos of potential places they’d come across already. Weighing up the pros and cons of spaces, from politically ambiguous grey-zone metal bars to the Hauptbanhopf central train station in the midst of a city-wide terror warning, even abandoned swimming pools with locks that needed to be cut. All sites had their unique points of interest, as well as problems but as Ying never acts as a permission-seeker to the venue or site used (with exception), the decision would have to be made on that single loop. It’s not only that a title needed to be chosen and conveyed to Ying’s exhibiting artists during that journey but that if the deciding party ran out of time, minority ruled. This information was then passed on to all earlier contributing artists via email so they could take part again, or invite someone else by forwarding the correspondence and a pdf of recommended reading for Ying. Those who confirmed by replying with a name were told simply to meet on the chosen site at 18:45. The show would open at 19:00.

Ying Colosseum hosted events that presented from five to over 20 artists, poets, singers. Crowd numbers could reach as high as 350 people in the course of the roughly three hours or so the show stayed open, often closing when the police showed up. Not just a reaction to the art scene and its all-too-common cliques, Ying also drew attention to the burden of gentrification and its effects on young art communities. As rent prices soar for housing and studio space in the German capital, cultural producers find solace and cost-effective answers to finding exposure via their Instagram accounts, but that’s at the cost of a safe, unburdened place to critique and congregate.

Ying’s final offering was the toolkit it created to stage these one-off events and the open-source license to use it alongside its name and mythology, created over the period it was initially activated. Ying Colosseum aimed to reveal the status quo and shield its users from it. One could argue that the project was never really interested in the artwork itself but the aesthetic discourse it generated through its human interactions; the behaviours and community it formed.**