If you exit Liverpool Airport, you might encounter a large steel cartoon-like vessel penned in amongst the taxi ranks and railings. It is one of many annoying public memorializations to local icons The Beatles that litter the city far and wide. I remember it from growing up in Merseyside, a weird vehicle to now see at an airport. I take a picture of it waiting for the bus, on my way to the 9th edition of Liverpool Biennial, running July 9 to October 16, 2016. The subject of a 1968 animated movie The Yellow Submarine, this human scale model used to be located in the city center at the foot of Chavasse Park (a bottleneck for adolescent social development) and was originally built for a themed flower festival in 1984 by shipyard apprentices. In 2005 the submarine was moved to the airport due to the park and surrounding area being re-landscaped as part of the Liverpool One retail development project in the build up to the city’s 2008 status as European Capital of Culture.

I am in Chavasse Park 2.0 on the threshold of Ancient Greece; one of six fictional episodes developed by the biennial organisers. I stand at the place where (to the best of my memory) the yellow sub once stood. I hung out here when I was younger and it is difficult to experience the city and the regeneration it has undergone as a tote-wielding art tourist.

Across the road from the new park is an Art Deco ventilation tower built in 1931 for the tunnel underneath the River Mersey. It becomes a backdrop to a bronze fountain by Betty Woodman titled ‘A Visit To Rome’ (2009). The cast components hang on an austere concrete wall with a bed of smooth pebbles that have been built for its display. It feels appropriate as an armature against the contemporary vista of glass and concrete monoliths that pronounce the modern waterfront. One of these buildings houses Open Eye Gallery with a ground floor installation by Koki Tanaka. Part of ‘Professional Studies: Action #6’, the artist re-staged a protest march from 1985 that 10,000 young people took part in against then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s controversial Youth Training Scheme with several original members and their families. Tanaka conducted video interviews about their experiences of the march as teenagers, which ended in the vicinity of the gallery at Pier Head. The interviews in the videos are honest and relevant to the current political crisis in the UK, as are the original photographs by Dave Sinclair capturing the marches from 1985. A surrounding installation of hoarding, barrier sleepers and replica placards feels strained against the video’s documentary focus.

Upstairs Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian use submergence as a political narrative about the status of objects and their movement. Three submersibles are described and documented through humorous video performances and a newsprint manual collectively titled ‘Operation Report’. They were used to smuggle artworks from the collection of the artists in shipping containers from Dubai to be hung within the installation.

The trio’s video at Tate Liverpool nearby displays footage of ISIS destroying ancient artefacts and monuments in Iraqi museums. Frame by frame, painted enhancements have been added to the scenes to alter the material. In several scenes a figure becomes a bikini-clad body with multiple breasts and no head. Several of the objects being destroyed are animated with anthropomorphic features. The abhorrent destruction of the objects is turned into a political cartoon. But what initially undermines Islamic State’s propagandist motive in the altered footage becomes a deeper critique of linear violence in the preservation of the artefact or document; the museum as a site of value and the symbolism it engenders in a western media context.

There is a reclining figure in Tate’s lobby surrounded by a pink tubular steel barrier; a character in Ancient Greece. This episode is populated with neoclassical figures and fragments from the collection of Henry Blundell within steel and wooden display systems designed by Koenraad Dedobbeleer. Blundell, an 18th Century art collector from Merseyside, amassed a large collection of neoclassical sculpture. Many of these figures were subject to inaccurate restorations and alterations; using fragments from elsewhere —an accepted practice at the time. The sculpture, originally depicting Hermaphroditus, had its genitalia altered to represent a female figure at Blundells’ request due to his distaste of the two-sexed Greek figure.

The Blundell objects could perhaps be used as an observation into a city built on episodes and versions —two submersible terms that we are accustomed to experiencing contemporary culture through, in the same way that the biennial is organised through a six episode fictional narrative —Ancient Greece; Chinatown; Childrens Episode; Software; Monuments From The Future and Flashback. There is a politics of transit in many of the biennial exhibits and a derailment by alternate forms of travel and cultural sampling. An example of this would be the popularisation of LSD in 60/70s music culture documented in films such at the aforementioned Yellow Submarine. Another example being the city’s current restaurant industry boom, post-2008.

Liverpool John Moores University hosts Suzanne Treister’s ‘HTF The Gardener’. The story of a fictional London banker who through a hallucination of stock exchange visual data embarks on a period of research into psychoactive plants. Losing his job due to research commitments, he moves to a penthouse next to Covent Garden Flower Market and makes drawings assigning psychoactive plants to FT Index companies. Exposed to the commercial art world by wealthy collector friends, he produces a sell out exhibition, but uninterested by this, continues his research into “the hallucinogenic nature of capital”. Triester’s project is documented in detail on her website.

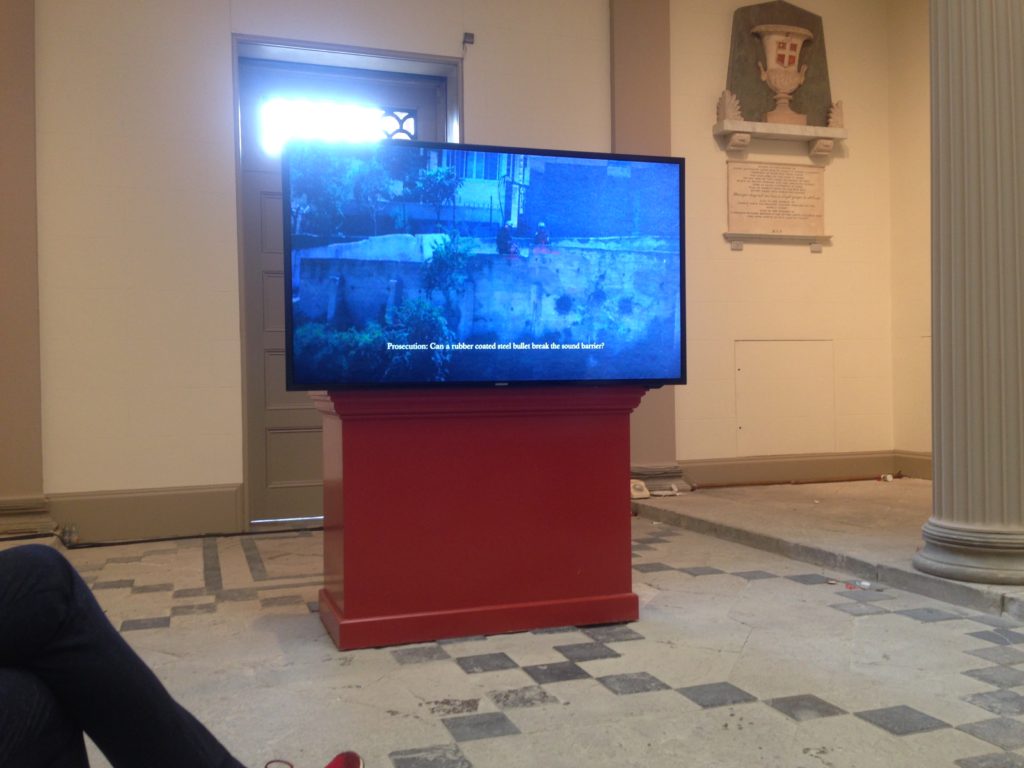

A further hallucination, in a small chapel I have not previously been in —The Oratory. Inside it works by Rita McBride, Lara Favaretto and Jason Dodge idle amongst neoclassical sculptures and an HD monitor on an odd, claret plinth. A transcription of a court case with visualised audio data that was used to prove the 2014 killings of Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher in the West Bank of Palestine were made by real metal bullets and not rubber ones, is contained within a cinematic short film by Lawrence Abu Hamdan. The illusory images, defect on their forensic function and responsibility. As graphic psychedelic visualisations they move in and out of focus through panning shots of a choreographed indoor firing range. Hamdan worked with the data as an audio analyst for the case. The scenes with which we are shown the evidence against the silence of the court transcripts push at the reality of the subject matter as literal matter of fact, to the point where you start to hallucinate the gunshots as the subtitles read (loud bang) and after (louder bang).

A mile south-east of The Oratory, the biennial map brings you through streets of Victorian terraces, cut with pockets of shuttered voids. On the Welsh Streets; five blocks of evicted housing host a towering granite boulder come donation-box, also by Favaretto. In a functional street elsewhere a steel domed sculpture by Alisa Baremboym, the exterior of which is made from bent sheets of the shuttering used to board up buildings. This work, from the biennial’s Monuments to the Future episode feels problematic in its co-option of a material that for many represents political and social displacement. Experiencing this as the final work on my biennial trip feels a timely conclusion to an instalment about an uncertain future. In two years time Liverpool will host its 10th anniversary biennial, a living metaphor of movement and place where until then, to quote The Beatles themselves, “nothing is real”.**

The 9th Liverpool Biennial is on across venues in Liverpool, running July 9 to October 16, 2016.