Taken between 1985 to 2003, the photography of Ultimate Paradox, showing at LA’s Château Shatto from December 12, 2015, to February 6, 2016, was produced during perhaps the most prolific, and public phase of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s career. The images follow the 1981 publication of Simulation and Simulacra –then followed by the book’s cameo in the 1999 film The Matrix– and were taken concurrent with Baudrillard’s very serious uptake by the international art community as both theorist and artist. It was into this ascendancy that he wrote the article ‘The Conspiracy of Art’ in a 1996 issue of New Left magazine Liberation, sending shockwaves through the contemporary art apparatus that saw his declaration of the nullity of art as a major betrayal.

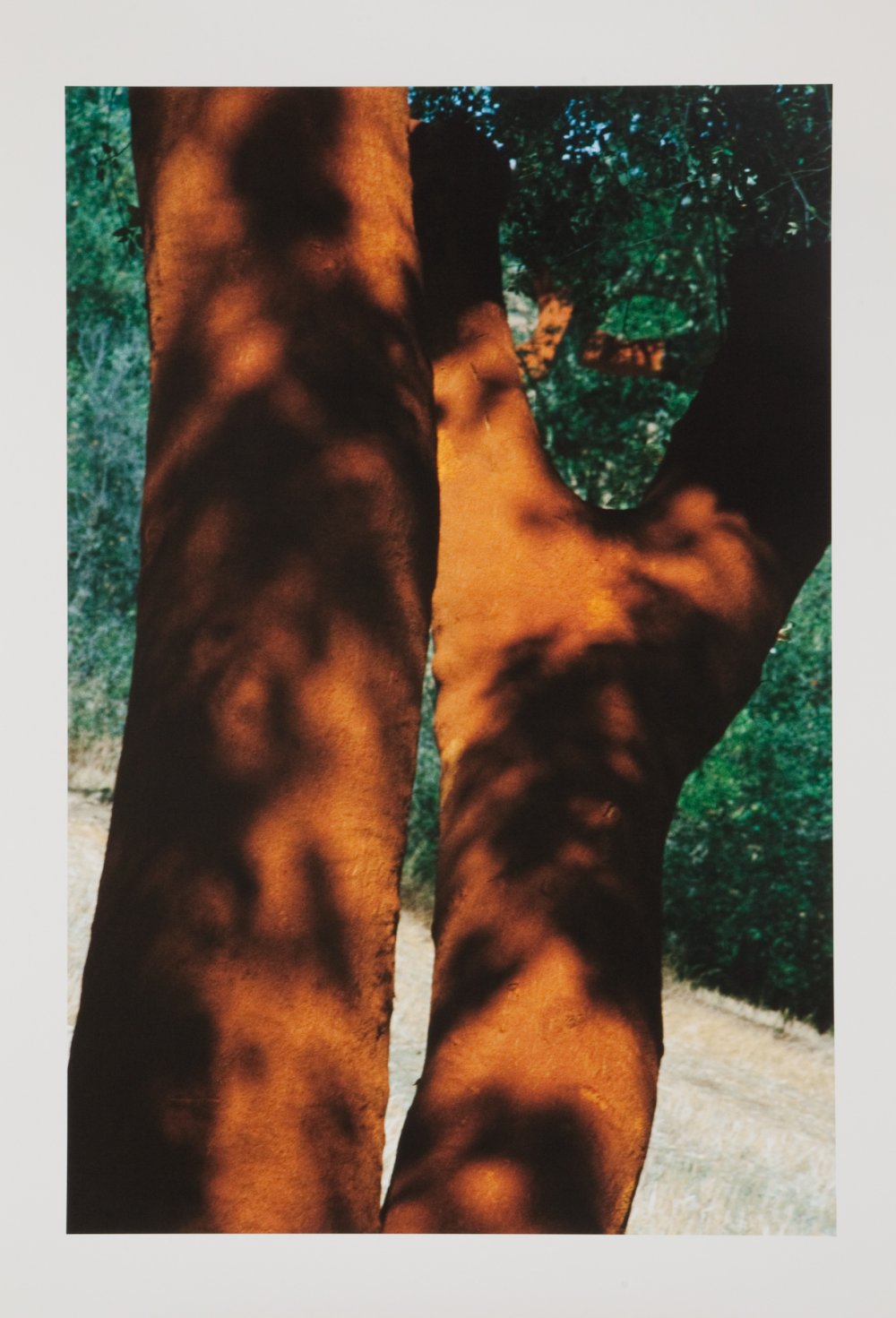

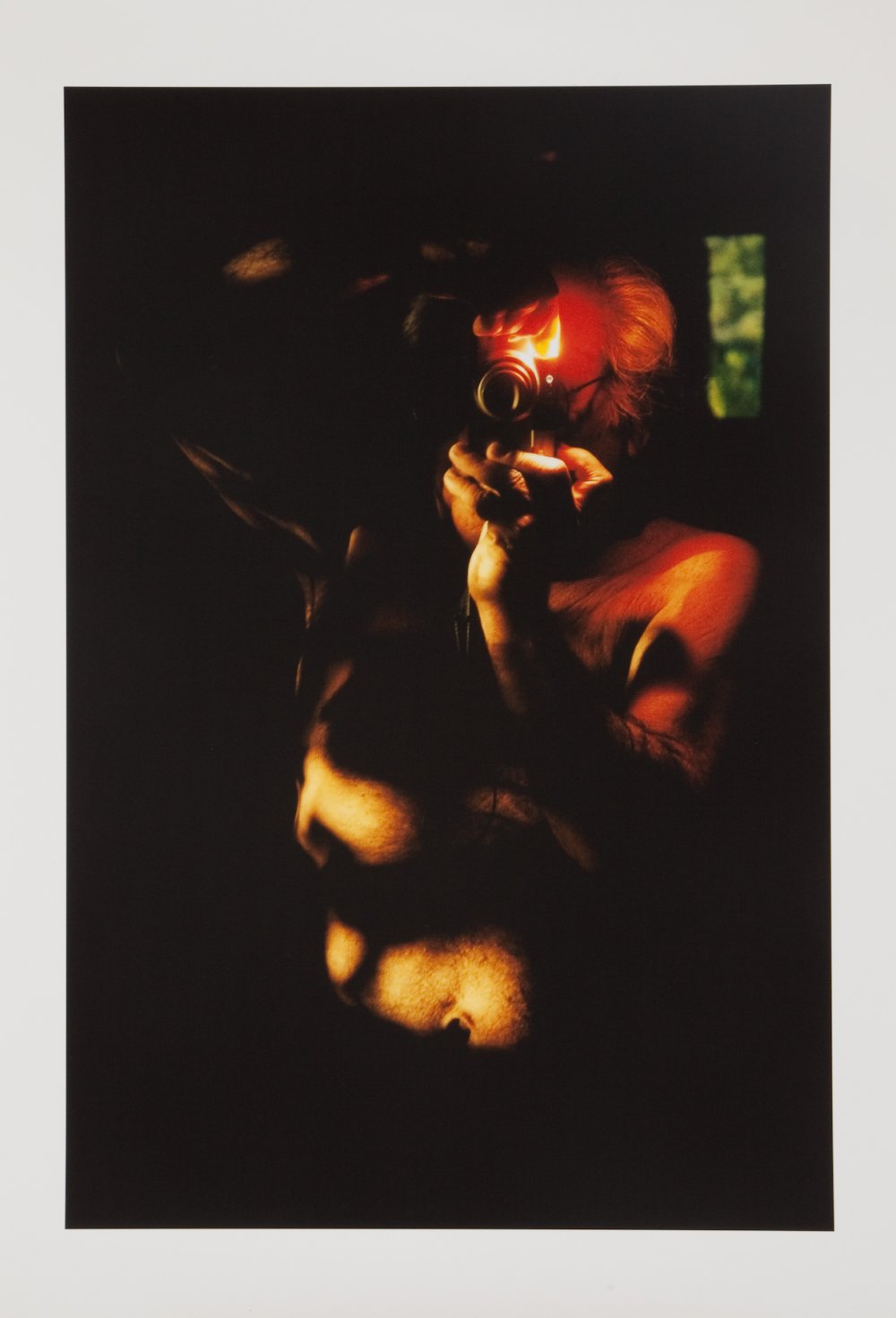

Yet, looking upon the subjects of Baudrillard’s photography reveals little regarding his stances towards art’s aesthetic banality. The images are largely absent of narrative content as he chose not to picture the human form –perhaps except himself in the image ‘Corbières’ (1999) –and instead focus on the formal aspects of mundane occurrences as he traveled throughout the world. It is fitting, then, that each work is named after the location situated in each photograph. ‘Las Vegas’, taken in 1996, shows the city’s airport and the double-silhouette of a distant mountain range with the closer geometry of airplane tails sitting on the tarmac. While this interaction of modernity and geology certainly hints at an emergent desert of hyperreality in the American west, it is the photograph’s formal statement that binds this scenario into his larger body of work.

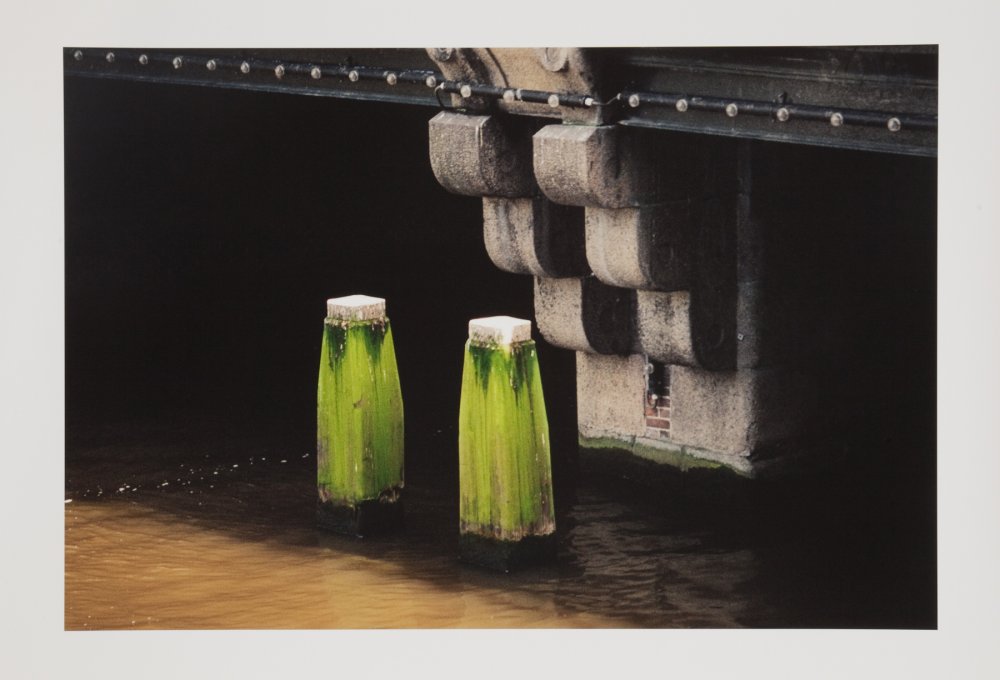

Photography presented a kind of documentary medium for Baudrillard, one where human forms and systems persist particularly in their absence. In a 1996 interview in Art Press, he reflected on his work, “That my photographs are beautiful or not does not interest me. The stakes are not aesthetic. It is more an anthropological arrangement that establishes a relationship with objects…… a glance on a fragment of a world allowing the other to come out from his or her context.”

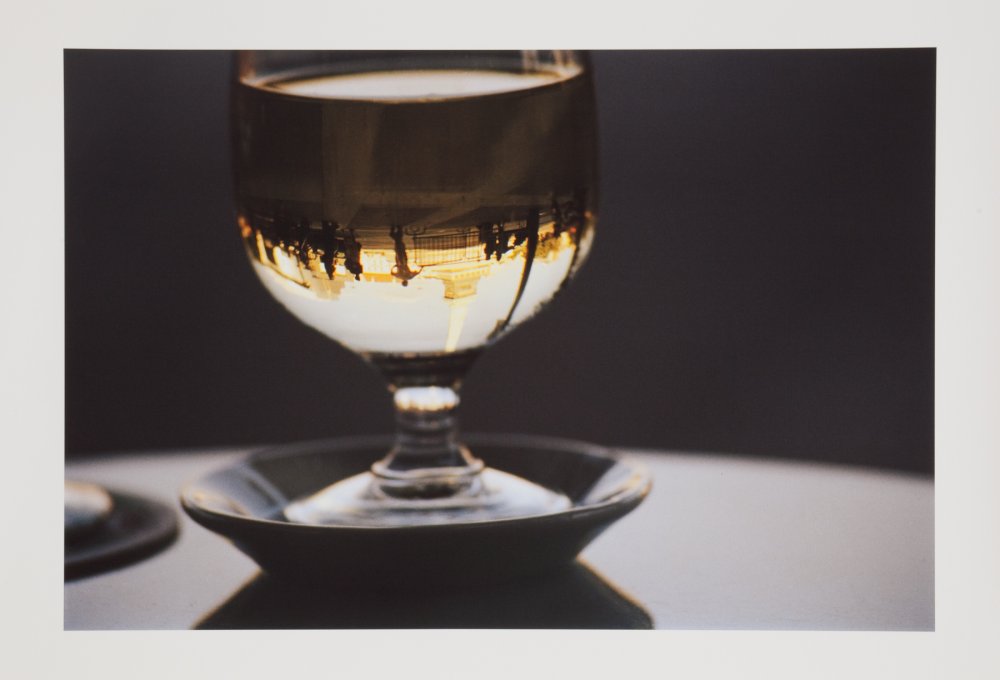

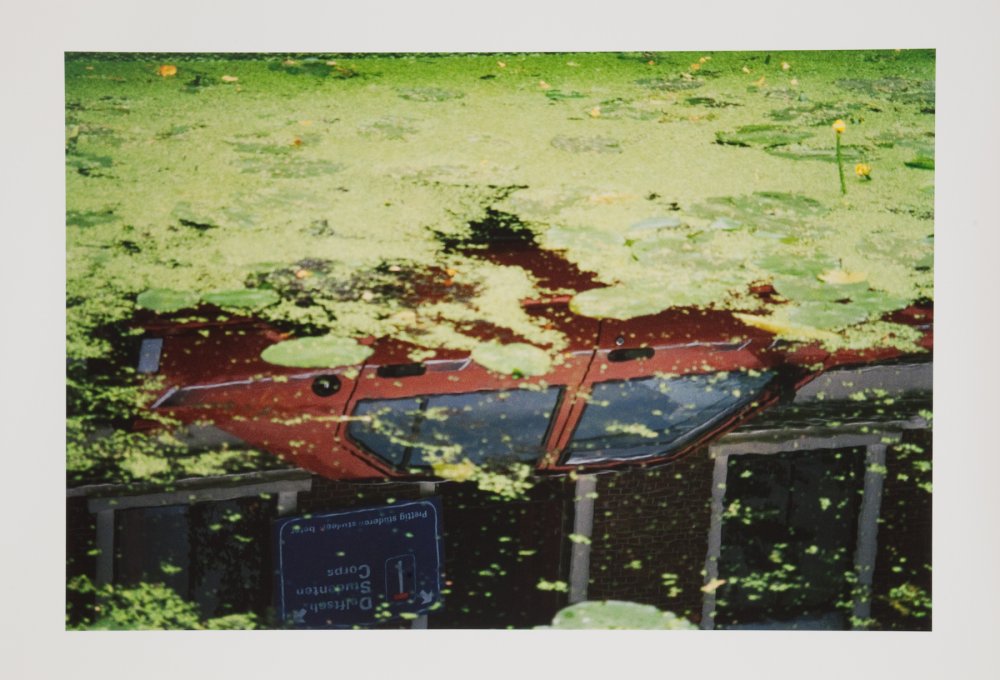

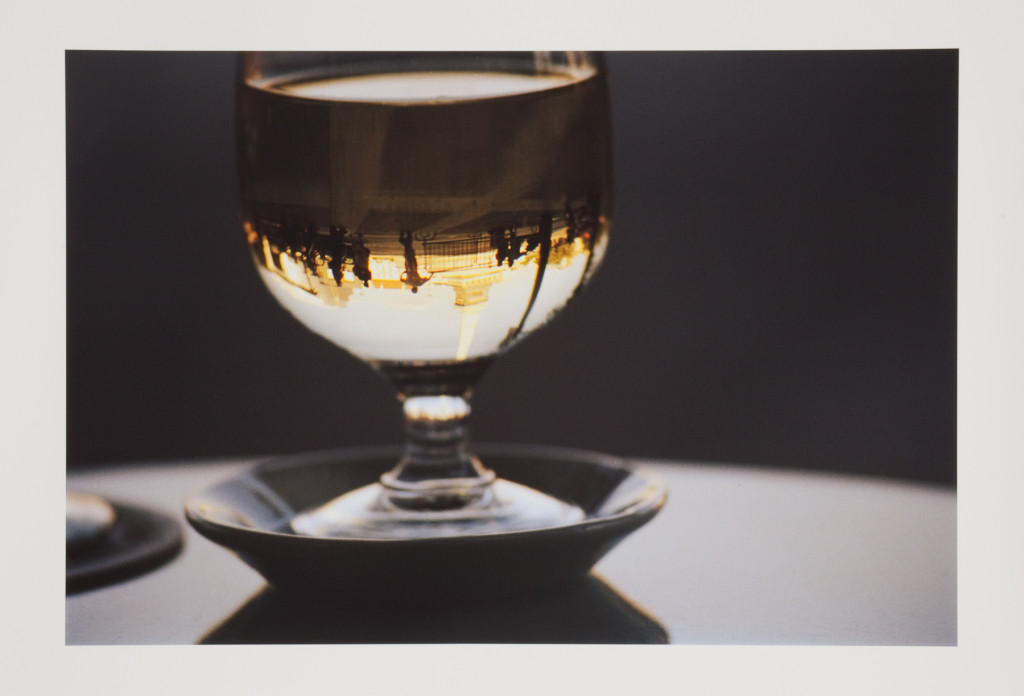

This kind of anthropology becomes highlighted in photographs taken in Rio de Janeiro in 1995 and 1996, where scrims, awnings and construction tarp become formal elements, encasing and revealing historical buildings in an uncertain urban terrain. Similarly, Baudrillard takes a noticeable interest in the formal qualities of reflections throughout many of his images. His seemingly ironic encapsulation of a glass of water reflecting an inverted Place de la Bastille in Paris echoes his 1997 portrait in New York where a street mural stands in opposition to apartment buildings curved in the mirror of a minivan’s tinted side windows.

Beyond this documentation of interstitial states and his musing irony between signified and signifier lie some of his best formal photographic works. ‘Venice’ (1989) displays the intersection of a cracked brick wall and downtrodden fence that together join to become a threshold to a beachfront alleyway with idle automobiles. ‘Sainte Beuve’ (1987) shows a chair covered in a red velvet-like fabric with visible impressions where the artist had once been sitting. This self-portrait explains the distance between the image and the real in his photography, as expressed through the artist’s absence yet irrefutable presence in the image, which also related to his theory of photography. In the 2000 essay ‘Photography, or the Writing of Light’, Baudrillard writes, “Instead of lamenting the relinquishing of the real to superficial images, one would do well to challenge the surrender of the image to the real. The power of the image can only be restored by liberating the image from reality. By giving back to the image its specificity… the real itself can rediscover its true image.”

It is through this odd grasp of interstitial moments, transitions and reflections of appearances, that Baudrillard reveals in his photography a conspiracy of the commonplace, a sincere de-mystification of the mundane. Assessing these images as a body, one finds that nullity in the human world is truly superfluous, and that the nullity of the everyday is full of form. **

Exhibition photos, top right.