The demurely titled A British Art Show, is the latest curatorial endeavor by artist/curator Joseph Buckley, a native of Leeds and recent graduate from the MFA program at Yale University. Eighteen British artists are featured in the exhibition, many of whom are also from the city of Northern England’s current site of the major survey and inspiration The British Art Show 8. A British Art Show is situated far from the motherland, in Meyohas, a newly-minted apartment gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Fittingly, almost all of the show’s twenty-five works exude a sense of displacement – both at home and abroad, real and virtual, political and spiritual, visual and textual … the list could go on. Indeed, from beginning to end, the show refuses to situate itself, continually doing and undoing its own assertions, creating a sort of no-man’s-land. In a way this survey, and Buckley’s curation of it, tacitly questions its genre, refusing to cast a grounding perspective, just as the high-rise buildings flanking the gallery’s sweeping panoramic windows block the horizon.

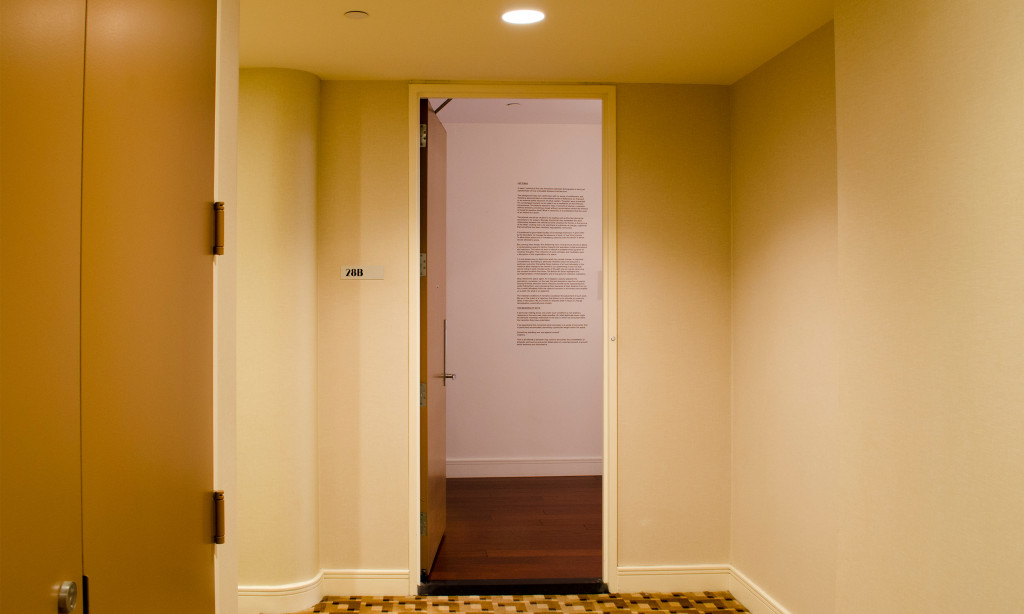

This lack of grounding is laid plain in the very first piece in the show, a text piece masquerading as institutional wall text. Hatty Nestor’s ‘A British Art Show – Text’ flatly outlines what an exhibition – and with it an exhibition text – ‘should be’, might be, even could be! But probably won’t be … isn’t. It casts a tone of ambivalence that resonates throughout the show, a sort of apology-turned-apologia whose only stance is to place the onus on the viewer for any shortcomings. The text wryly states that the fate of the exhibition lies in the hands of “whoever may come to encounter” its “uncertain ground. A ground,” it challenges, “which beckons your disturbance.”

On the way to the narrow corridor to the main space, one might miss (as I did) a wall-sconce on the upper register of the wall – a flickering, electric candelabra, held up by a live human hand through a hole in the wall, ‘R U Next’ (2014) by Kitty Clark. If one does manage to remark it, this blatant exploitation, literally, carries on, and is quickly forgotten as we consume, and are consumed by the unfolding show. This overtly exploitative, yet functional apparatus becomes a commentary of the one in which we are an integral part.

The exhibition as a whole carries a self-deferential tone perpetually asserting a position, and then promptly erasing that gesture. Perhaps, as a result, the content at times slouches towards self-reflexivity. But make no mistake – it packs a hell of a punch. Each successive piece implicates the viewer, some more subtly than others, holding them to some degree accountable for the general inertia.

A take-away piece by Ruth Angel Edwards starts with a rhythmic, declaratory critique of North American consumerist culture, but then accelerates into a manifesto, or rant, that is punctuated at the end by a link to the artist’s website. Is this just an oversized business card or an anti-capitalist leaflet? Either way, it instantly becomes possession, which we can accept or refuse.

In David Steans’ ‘Villages of Britain’ (2015), a series of speakers read an original text based on Channel 4 documentary Penelope Keith’s Hidden Villages – a search for “a rural idyll that may no longer exist”. They fudge and fumble the text as a reel of vintage Reader’s Digest images of English villages troll on, backed by calming, repetitive music also written by Steans. Were it not for its playful, but earnest readers and composition, the piece itself might fall victim to the fate of many of the villages pictured, whose “self-conscious kind of beauty is anathema to our idea of a perfect village”. Instead, the repetitive format with its sonic variations open the work to varying tonalities which evolve and unravel over the course of the twenty-five minute long video. In the end, the predictable, tight-lipped, coy narration releases itself and becomes something other – we are placed with a rider on a headless horse, riding, endlessly, direction unknown. Is this transcendence of the prior, measured speech or is it a condemnation to an endless trot around relentlessly picaresque, fundamentally inert, and essentially English, villages?

Again and again, Buckley chooses works and pairings that raise this type of quandary, leaving us to wonder whether we ourselves are riding a headless horse. The show repeats and folds in on itself, shrugs and excuses itself, points in one direction and the other – condemning itself, and the audience along with it.

But Buckley knows exactly what he is doing. The exhibition layout mimics the neurotic atmosphere created by the work. Buckley conceptually and physically leads us through a spiral. Structures from the work are redoubled in the space. For instance, tudor-style beams from Francis Lloyd Jones’ c-print are blown up and projected onto the main room of the space in a vinyl cut-out, Harlan Whittingham & Benjamin Slinger’s video is shot in the kitchen of the gallery, but prefigures the actual kitchen in its placement. As the exhibition circles in on itself over, and over, one has an acute sense of déjà vu, like a punchline that relentlessly repeats itself.

Buckley has also constructed an actual spiral out of the space, cutting off a wall which would allow it to loop. The dark heart of the spiral is a literal déjà-vu: a dead end, and the rear-end of Clark’s sconce-arm, and perhaps the butt of what has become a not-so-funny series of jokes. An individual wearing a black hoodie and blonde wig hunches atop a ladder, their arm plugged into a false wall. A paper is pinned to their back, reading “Somebody loves you”. This is actually Clark’s second piece in the exhibition, ‘New Scum … Somebody Loves You’. As viewers raid the refrigerator for beers during the opening, the exploitive image is concealed, and re-revealed, over and over. Here, one is not only reminded of the hand-sconce in the corridor – but also forced to face the act of viewing, and looking away, as the treachery that it is. In order to exit the exhibition, one must literally turn their back on the stark image, itself almost a sneer, and backtrack; redoubled images, re-presenting themselves. Finally released into the hallway of a New York City apartment building, we cannot be sure from whence and where we came. And maybe that’s precisely the point. **

The A British Art Show group exhibition was on at New York’s Meyohas, running October 23 to November 13 , 2015.

Header image: A British Art Show (2015). Exhibition view. Courtesy Meyohas, New York.