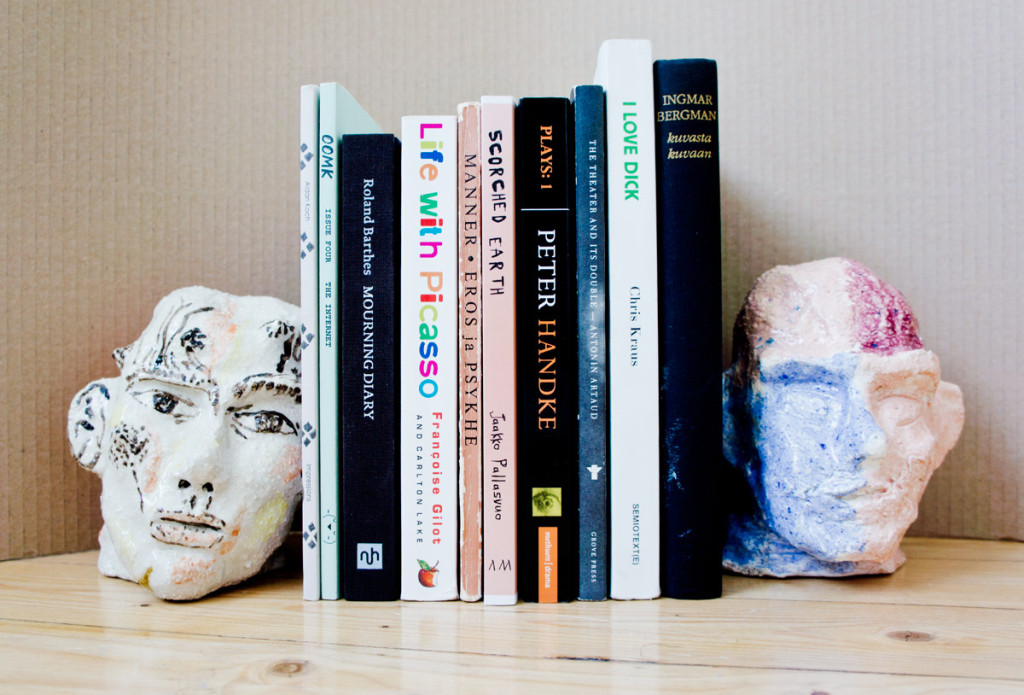

“How long will it take for you to recognise my brilliance?” asks Jaakko Pallasvuo, on a list numbered fifteen, under a title reading “Works”, in a book called Scorched Earth. Most of these ‘works’ are speculative, conceptual art in the form of performative text that reads in sentences like, “I listen to her talk about her work. I nod. That’s nice, I say”. Some of the immaterial pieces exist merely as a blank space on paper, next to a number that’s the sum of a section, that makes up a novel, published in a limited run of a hundred by Arcadia Missa in August.

The book of sorts –an object –consists of a collection of contemplations, fragments, online posts, chat boxes, that are cobbled together from the Finnish artist’s dawsonscreek.info Tumblr account with a quote on the cover by the blog’s namesake, Dawson Leery (“We can analyze this to death later”). Off-topic and out of context, it’s a pull quote made by a fictional character from a turn-of-the-millennium US teen drama, about an artist he doesn’t know. Because how could he? Dawson Leery doesn’t exist. But he also does. He’s an influence on Scorched Earth, along with other pop cultural constructions, Rihanna, Kanye West, Chloë Sevigny, Eddie Vedder. They all compose a highly allusive maybe-autobiographical text that’s based in the circulated image.

“The text is not the work”, insists one of Scorched Earth’s fifteen “Works”. Neither is the artwork the life that’s led; one made up of fragments filtered through a body that is odd looking, neurotic, fat, fictionalised (“either a man or a woman or then not”). Here, the online and the offline are indistinguishable, the internet is the IRL, the image, the reality. Nominating himself a kind of Saviour come to reclaim poor Post-Internet (“I want what no one else wants”) Pallasvuo disavows any idea of authenticity: “isn’t it more authentic to be inauthentic than authentic if you’re inauthentic at heart?”

Purporting to a rejection of authenticity while finding it by the very act of that rejection is as far as the irony goes, though. There’s no distance in Scorched Earth. It recognises the absurdity of its own position as a book about the art world by a persona who doesn’t feel a part of it, but also actually is. Pallasvuo might not make it into Wolfgang Tilman’s Frieze celebrity after-party, but still the open and anonymous Quaker meeting he’s been to isn’t as desirable. “The usual case is that the Wolfgangs of the world don’t want us to come in but don’t want us to leave either”. It also works the other way. As much as the artist doesn’t want to be a part of the art institution, he also kind of does.

“’Scorched earth’ is a military tactic of utter devastation and a video game, and now it’s a book”, John Beeson opens in an adulatory Afterword at the back of the book. The book in turn is a deeply personal account of the art of war in the war of art –a game that can transform a crippling self-reflexivity into a creative strength. “You take everything you’ve got, your failures and insecurities. You repurpose, repackage, relaunch and repeat until they are categorized as successes.” In the case of Scorched Earth, you write bitter fan fiction about an online troll, fantasise about the “marble and vapour” of a New York City art scene, and lambast an opinion piece on the artistic significance of a Berlin-based “friend group”.

“Competitive social spheres appeal to me”, Jaakko Pallasvuo writes, quoting an imagined art figure called ‘Brad’ who’s blowing a guy called ‘Boris’ while attesting to choosing his field for its cut-throat competition under the guise of thwarted idealism. It could be Simon Denny, Timur Si Qin, Daniel Keller, Tobias Madison, or any number of artists and people Pallasvuo names (he does so selectively) in Scorched Earth. It could even be the artist himself. (“Brad swallows”). **