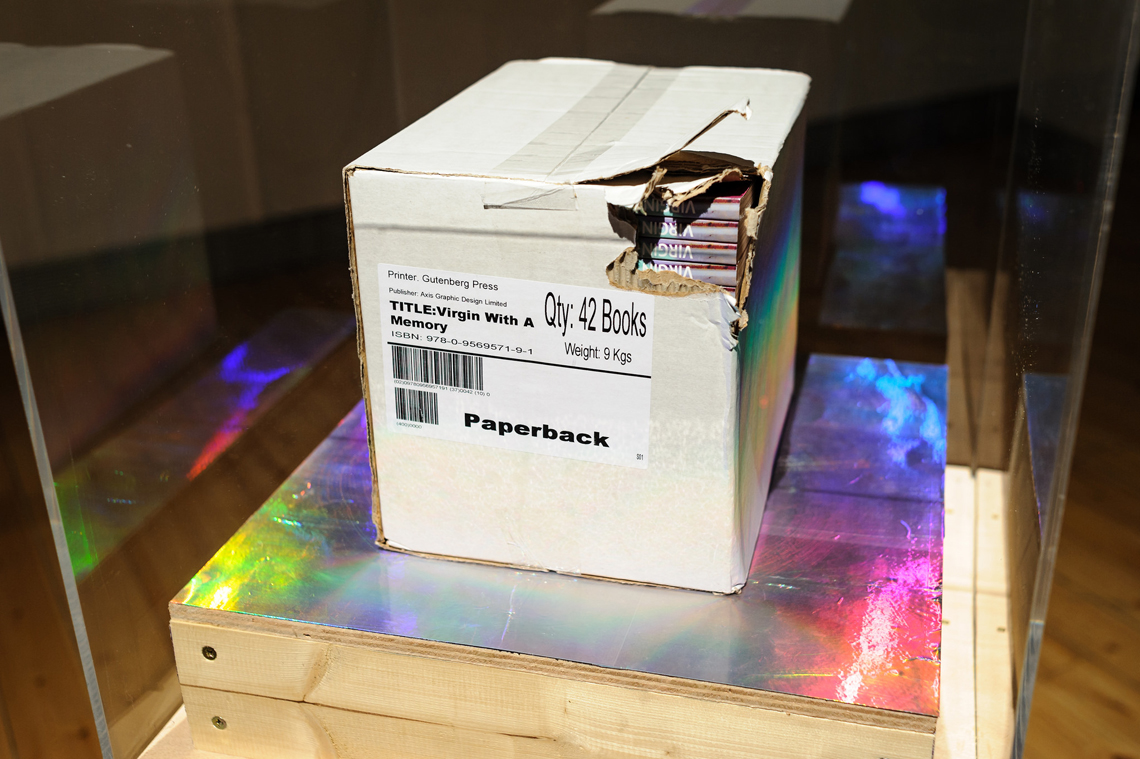

When I speak to Sophia Al-Maria, I haven’t read Virgin with a Memory yet. It’s the companion text to the London-based artist’s solo exhibition of the same name –opening at Manchester’s Cornerhouse on September 5 –and one so evocative and unsettling that I suspect the interview might have gone differently if I had. “Something delicious and fresh about the violence”, says the sentence fragment about an unnamed film set in Belfast (“blown up”) in a note dated March 10, 2014. It’s nestled among the collection of emails, diary entries and fictional narrative; headshots, script excerpts and kit lists, making up Virgin with a Memory: The Exhibition Tie-in and could just as easily be applied to its content:

“So let’s spend today thinking of ingenious ways to hide and dispose of bodies and discuss tomorrow

See you tomorrow

Producer One”

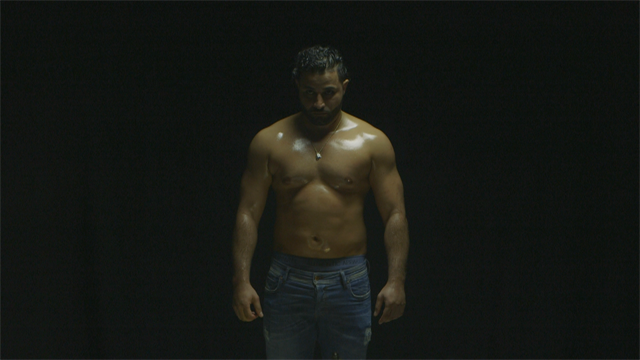

“For some reason I keep being dragged back to these subjects”, Al-Maria chuckles, between sighs and over the phone from her hotel room in Manchester. She seems exhausted, and not just because I’ve caught her in the middle of the Virgin with a Memory install but she’s on the line to talk about a feature-length film she’d spent the last two-and-a-half years working on, only for it to essentially come to nothing. “This show is not a eulogy but a way of displaying all the supplementary materials that went into working on the production”, she tells me about the collection of pseudo-documentary footage and video installations built from the remains of Beretta. It’s a film that would have been a rape-revenge thriller set in Egypt and inspired by Abel Ferrara’s cult-classic Ms. 45, where mute and man-hating prey becomes predator on a killing spree after one too many abuses.

As a fan of Al-Maria’s work and writing, I’d read her memoir The Girl Who Fell To Earth, watched her videos, and seen the work of eight-strong collective the GCC. I followed her blog and more writing on Gulf Futurism across articles in Dazed and Art After the Internet. None of it could prepare me for this:

“I could barely shut the refrigerator door. I had to put his head in the freezer. In the end I used the electric carving knife to get through the tangle of bone at his back. If I had a machete it would have been easier.”

The body above is not just human but ‘tomcat’, or ‘pig’, depending on which simile you choose to describe the men Beretta’s heroine, Sueda, murders as revenge for their part in making her life a living hell. Scattered in fragments across its Virgin with a Memory novelisation, the film-that-would-be is a product of Al-Maria’s own experience as a student in Cairo, set to the backdrop of the 2011 Arab Spring. “Beretta is not only the story of a mute, repressed woman pushed to extremes by her environment,” Al-Maria writes in an excerpt of explanatory notes as part of the book, “but it is the story of a people, raped and degraded by their government, culminating in revolt.”

I remember you writing in The Girl Who Fell To Earth about your experience of Egypt, where you were basically assaulted.

Sophia Al-Maria: Many times. That was one example.

Because the country has become known for being one of the worst countries in the Arab world to be a woman?

SA-M: Well, in the same way that Mumbai is famous for what has been going on there with mob attacks. Certainly, it’s become aggravated by the general chaos of post-2011. In the past I’ve been involved with and continue to support activist groups [in Egypt] trying, from the ground up, to help combat this problem of harassment on the streets. The real issue is that, within living memory, if a man was caught harassing a woman in the street in Cairo, the people who witnessed it would grab him and shave his head so that he would be publicly humiliated.

That just doesn’t happen anymore. Everyone sort of acquiesces to the general anger and aggression of frustrated men. I think that it doesn’t matter with regards to culture, as much as a mixture of over-population and repression. If London was as crowded as Egypt is, I suspect that there would be much more public harassment on the street.

You talk about the film in past-tense, is it not going to go ahead?

SA-M: The film will go ahead but in a different form. We got funding and were waylaid by legal issues at the very last minute, which are hilarious because the financiers wanted something called ‘right of title’. Abel Ferrara, who made the original Ms. 45, was very into the project and was very supportive but then it turned out that the original porn company who produced Ms. 45 had disappeared and Warner Brothers had bought the rights. Then it turned into this kafka-esque farce of trying to get the rights to this movie.

Plus the writer of the film, Nicholas St John has become a monk and moved on top of a mountain somewhere in France, disavowed everything he’s ever done and refuses to sign anything. So in the end we were stuck because somebody somewhere along the line stuck his foot in his mouth and said we should get the rights to this movie so that we can say it’s the ‘Egyptian Ms 45’ which was a huge mistake.

So I’m rewriting it, basically. I’m hopefully going to the Sundance Screenwriters Lab this January and restaging it elsewhere, not in Cairo, and trying to get it back on its legs in a new form. It’s a universal story. I just wanted to set it in Egypt because that is the root of my interest in the subject matter and my experience. But I think there are many other places in the world where this is equally relevant.

In the blurb for Virgin with a Memory, it says a Beretta actress was arrested?

SA-M: Yes. Not the main actress but the second lead who’s the heart of the film. She’s the reason that a lot of the events go down. I wanted there to be a sort of sisterly friendship that causes the revenge, not just what happens to the main character. The main character is raped and is unable to speak to anyone about it because it’s a cop and she internalises all this fear and anxiety –what to do with the body and all these things –until her best friend is compromised and she then goes in and saves her from a sort of bunga bunga party situation, which she has found herself in.

So the actress, who was incredible and blew everyone away in the audition, was unfortunately put in jail. She’s in for a year, which will be up, I think, next spring. She was in the wrong place at the wrong time, accused of smuggling drugs and used as a scapegoat because she was very popular on television at the time. One of the videos that’s in the show [‘Class A’ (2014)] is a sort of love-letter to her. It’s using her audition tapes with footage of an interview she gave where the woman interviewing her is this sort of evil Nicole Kidman type who is being so cruel to her and asking her questions to try to sort of throw her off. There’s these really aggressive bits and then these fractured images of her audition tapes mixed in with it.

I watched the two year-old promotional video for Beretta on vimeo.

SA-M: Yeah. That was done before we got the producers involved; it was just me with a thirty-page version of the script. I’d been in Cairo with a friend and shot some of that stuff with a Nokia, and some random evening cut it together. It had a bit of the vibe of what I wanted and there’s going to be a companion piece shown at Manchester, which was done without my knowledge by the producer.

He took some rushes that we had shot in Cairo and then made this thing to try to convince financiers; he had done a little shoot with the actress on his own and everything, which I found… he really had gone behind my back as the director. So I’m displaying that as well, as a sort of example of the power dynamic between producers and directors these days, which is shifting more and more to the producers, as money gets more and more difficult to raise.

That’s interesting because if you think about that in conjunction with your involvement in the Whose Gaze Is It Anyway? exhibition, when a producer –who I’m assuming is a man –shoots with the woman lead without your knowledge…

SA-M: Yeah, and saying it was a surprise [laughs]. I was working on a new draft of the script. I met up with him after I’d finished and he said, ‘I have a surprise for you!’ and he shows me this ‘taster’ for the financiers. He’d shot this stuff with her and used a Kanye West song underneath. It was a bit of a creative rape moment where, ‘you’ve just taken this thing out of my head, put your own spin on it and then shown it to the people who are supposed to be giving us money. And this is completely not what I want’. It has the actress putting the gun in her garter belt. It was all very, sort of like ‘gaze-y’. I think he worked very hard to get the project where it is, or where it was, and he got a little carried away at that moment. I think in retrospect he understands that [laughs].

Kanye West is an interesting choice.

SA-M: Yeah it’s funny, of all people.

You also mentioned the relationship between directors and producers is shifting as it becomes harder to raise money, that’s pretty much a universal theme when it comes to economic and social stratification.

SA-M: Yeah, things are polarising and its this, sort of, drift. It’s the one per cent and 99 per cent. It’s the corporation and the individual. It’s all of those things. I think these little titles like ‘producer’, or ‘curator’ or whatever will eventually become irrelevant when it becomes ‘studio’ and ‘content’ [laughs]. It’s interesting; things like television, for example, where the director’s role has been massively downsized and now it’s writers who are the show runners. Writers rooms are far more in control and directors shuffle in and out as workmen, or tradespeople on shows. Things are really changing, I think. This is a totally random sidenote…

No, I think it’s all relevant. Like you say, writers are running the show. Even when you think about how history is written, you have a specific set of people who have the privilege of writing it.

SA-M: Yeah absolutely. People link that shift in power to the writer’s strike a few years ago in the US, which then led to things like The Sopranos and these big showpiece series’. And, of course, that’s all about the strike, and about the collective, right? Writer’s finally putting their foot down and taking power but I don’t know what the moral of that story is.

When you think about it, the outcome is Breaking Bad, Mad Men, The Sopranos. They’re all pretty macho.

SA-M: Yeah, and actually the one’s that are overtly trying to subvert that are often really unsuccessful, like The United States of Tara or… there’s one recently with Laura Dern…

Enlightened.

SA-M: Yeah, yeah. I mean, these ones, you hear about them and stuff but they’re not like Game of Thrones or True Detective –which I am so pissed off about, it’s not H.P. Lovecraft, fuck-off everyone. It’s just macho. It uses women as props in the shows… there is much to be torn back because, again, writers’ rooms, as with most things, are still male-dominated. I guess you have your Lena Dunhams but they’re tokenised.

I read an interesting observation that in art, it’s an industry that’s so low-paid and it seems to be woman-dominated, at least on an administrative level.

SA-M: [laughs] Yeah. Hey, there can only be one explanation and that’s money. If you follow the money, you’ll get your answers. Always. **

Select arrow top-right for exhibition photos.