Outside of the close-knit rings of academia, terms like “design fiction” and “speculative realism” have had little bearing on the design world, only provoking linguistic confusion and at times, honestly, snickering. I mean, what could sound more redundant, more obstinately ridiculous than the paradoxical pairing of “speculative” and “realism”? What, if anything, does it mean?

The response to a recent email titled “What in the Fuck is Speculative Realism?” and sent to a friend at the closing stages of her art history PhD proves this reaction also extends to academics. Her answer, so long as it can be summed up in words, was lines of coded laughter and then only: “Any more first world problems for today?”

I’m not sure there’s a better working definition than that, but Jon Sueda’s All Possible Futures, published by Bedford Press in conjunction with the 2014 exhibition of the same name, believes it is at least a question worth asking. Many of the designers and designing collectives he invites to share their views in the multi-format, mostly textual book, however, tend to vehemently – at times barely respectfully – disagree. When Sueda posits the very definition of “speculative” as a question to the various participating designers – consisting of individuals like Ed Fella and Willem Henri Lucas as well as collectives like Experimental Jetset and Zak Group – the answers are divergent, contradictory, expressive of abstract and theoretical contexts, married to economic and logistical considerations, exasperated, hopeful, confused.

I appreciate this strategy, this inclusion of antithetical and at times paradoxical working ideologies –the punky materialism of Experimental Jetset; the theoretical wariness of Seoul’s Sulki & Min; the expansive ‘designer-as-author’ ethos of Lucas and Jürg Lehni. It seems not only the honest and requisite approach, but also one that, through its very format, enacts the critical discussion of graphic design whose absence Sueda laments throughout the book. And though the viewpoints represent a mixed bag of philosophical, political and stylistic leanings, a certain consistency of thought emerges from their myriad musings –a modern vein, a new conceptualization, a novel approach that is starting to take form both conceptually and formally in the design world.

In each of the sections in All Possible Futures, consisting mostly of a collection of interviews and interspersed with short essays by Sueda and Max Bruinsma, there is a common thread: the re-conceptualization of the notion of design and a reinvention of its very role. Sueda hints to this in his opening essay when he presents the book as a “radical questioning of many accepted rules regarding graphic identity,” and this idea is echoed throughout the book in the responses of each of its diverse contributors. In an interview with Emily McVarish, she reiterates this shift, this “crowding at the core and breaking at the seams of graphic design as a field”, as does Bruinsma in his essay when he says: “More important than the precise form of the end product, in that case, is the way it comes about, the mentality with which it is devised and the analysis that underlies it.”

The sentiment reverberates throughout the subsequent interviews, at times somewhat subconsciously, as when Experimental Jetset spurns the term “speculative” and even the practice of critical theory but later presents the breaking of “the spell of the image”, the awareness of its material existence and preceding creation, as their design objective. Likewise, this interdisciplinary reinvention of the role of graphic design is peppered throughout the statements of Lehni and Lucas, who use phrases like “wearing different hats” and “the designer-as-author approach”, respectively, and expounded quite clearly by Zak Group in the following excerpt:

“In using the strengths and skills available to graphic design, we see the studio as a platform through which we can expand the notion of design production to encompass activities such as publishing, editing, writing, curating, and exhibition-making, even within commissioned projects.”

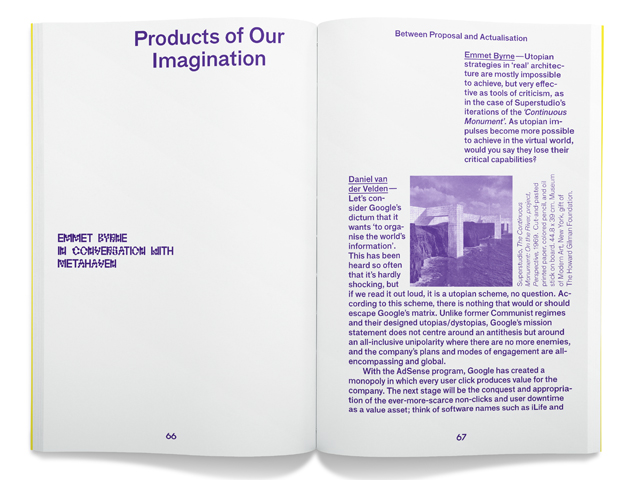

Following these diverse but increasingly unified perspectives is a short interview with the members of Metahaven, a graphic design agency whose spectrum incorporates everything from policy documents and publications to the creation of visual identities and conferences, and whose 2010 book Uncorporate Identity defies the very notion of clear categorisation. In the chronology of Sueda’s All Possible Futures, their very presence reads like the answer to one of Sueda’s earlier interview questions, namely: what is the future of graphic design?

Vinca Kruk of Metahaven responds to this plainly and poetically:

“For us it starts with avoiding making a division between graphic design, architecture, art, politics, and theory, and avoiding differentiating between ourselves as designers versus human beings. It’s interesting to see what comes after postmodernism and post-postmodernism. It’s all about using the remains of the ruin, making the debris of utopian projects productive.”

And so the evasive definition of “speculative” and the indeterminate direction of design-at-large begin to find their form in the pages of Sueda’s book, at the very place at which they intersect. The notions of creativity, of speculation, of re-imagining are found not in the aesthetics or concepts of their designers but in the very breaking of boundaries and in the critical spaces that hang between disciplines and ideologies.

As an epilogue to the book and a final nod to this near-future conception of design, Sueda includes the critical prose of Rachel Berger, whose take on the question and whose very inclusion in the conversation is left hanging like a hollow ring through a noisy room: the very stuff of which future design is made.**

All Possible Futures, edited by Jon Sueda, was published by Bedford Press in February 2014.