A legendary figure in publishing and theory in the US, the French-born Sylvère Lotringer isn’t only credited with bringing the ideas of French post-structuralism to the US through his Foreign Agents semiotext(e) series in 70s California. He could also be recognised as ambassador of a contemporary art aesthetic; Baudrillard’s ideas of simulacrum infiltrating postmodern design, from the pioneer digital media of April Greiman to the grafitti of Futura 2000, a baroque hyperreality trickling down to the decontextualised retrofuturism of the likes of LA-based Not Not Fun bands like Maria Minerva, Dylan Ettinger and beyond.

Lotringer’s influence as a taste-making medium is immeasurable: the Baudrillardian foundation of the Wachowski brother’s The Matrix at the turn of the century, Deleuze and Guattari’s effects on modern Western thought, their rhizomatic ideas pre-empting internet culture. He’s a man who had a friend in Leonard Woolf, learnt English through the writings of the latter’s late-wife, Virginia, and drew parallels between French post-structuralists and downtown New York’s Fluxus writers, leading to the Foreign Agents. It’s this disregard for distinctions and their transgression that makes Lotringer such an influential figure and fascinating character.

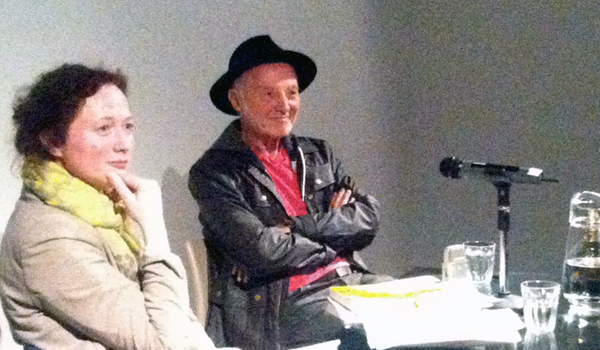

Come to South London Gallery to speak in front of an audience with multidisciplinary artist and film maker Katherine Waugh, a funny and profoundly intelligent 75-year-old thinker talks about Antonin Artaud and The Question Itself. A writer and theatre director who “never had a work” and whose letters to the editor of literary magazine La Nouvelle Revue reflects his function within the present, Lotringer proves Artaud as never more relevant than in this current era of immediacy. Accordingly, interest in the French founder of the ‘Theatre of Cruelty’ has been reignited, particularly in art circles, and as a long-time admirer whose own life and philosophy intersects is here to discuss him before inevitably turning to semiotext(e) and writing as art, within nearly two hours of discussion.

Echoing the thoughts of long time collaborator and Native Agents Series founder, Chris Kraus, who spoke at the RCA in March, Lotringer jokes “the problem is that the art world is eating everything up, and I’m not a big eater”. Interesting, considering the limitlessness of his critical engagement. Between organising the infamous “Schizo-Culture” conference in 1978 and screening his 14-minute video collaboration with Kraus, ‘Voyage to Rodez’ (1986), one is tempted to assume otherwise. Especially when reflecting on the transplanted articulations and contexts of the film, set at the French Rodez asylum, where Artaud was controversially administered electric shock treatment by Dr. Gaston Ferdière, shot on North America’s Rhode Island. And that’s not mentioning the combustive cultural and lexical antagonisms of the aforementioned Columbia University symposium that interrogated the prison system and psychiatry among eminent thinkers like Lyotard, Guattari and Burroughs (or as he puts it, “a collection of weirdos, you can’t imagine”).

That self-contradiction and tension is almost a necessary by-product of Lotringer’s philosophy. From the assertion of “all utopias as [being] inevitable dystopias”, to the truism that “to be aware that you’re alive, you have to be aware that you’re dying”, Lotringer shares Artaud’s compulsion of showing his audience the stark truth that his ‘impossible theatre’, in all its ambiguity couldn’t. Hence, Artaud’s resurgent significance as a 20th century thinker, echoing 21st century pseudomodernist ideas. It’s that of emergent meaning in a context continually in flux and always in progress; “the question itself” that underscores all life as always unfinished and forever incomplete: “You don’t embrace a philosopher, you just live with them… let people take what they want”. **

Header image: Photo by Pieternel Vermoortel. Image courtesy of SLG.