If you haven’t seen Yayoi Kusama’s exhibition at London’s Tate Modern yet, then you should. That’s if for nothing more than to step into the experience of mental illness with her famous Infinity Room at the end of it. Before you reach that spectacular and slightly terrifying installation, though, the retrospective tour of a life’s work provides some fascinating historical insight.

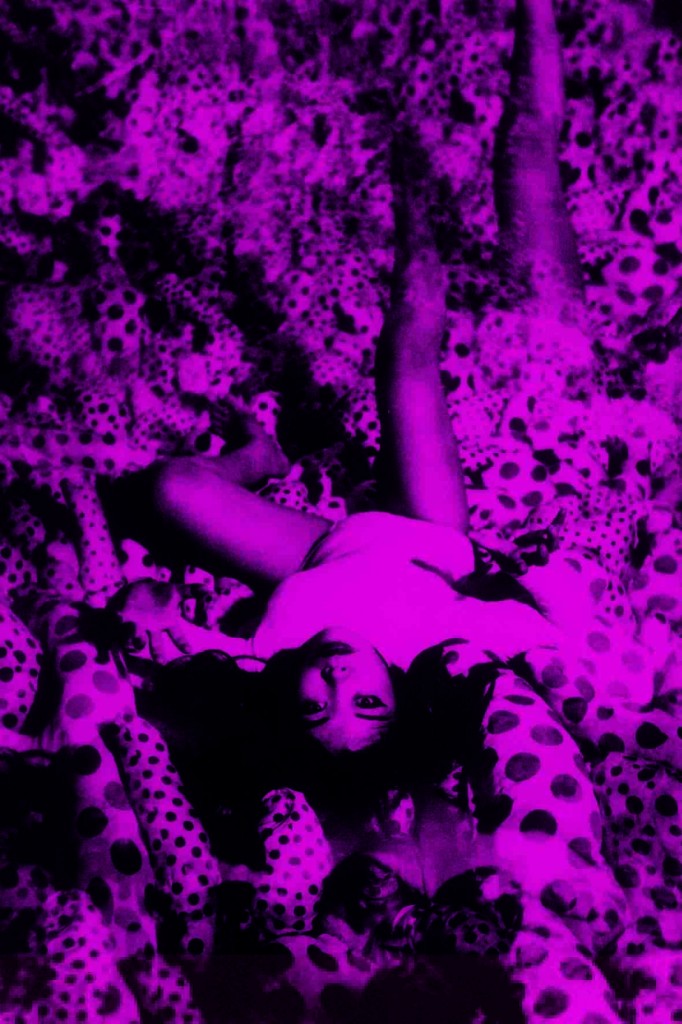

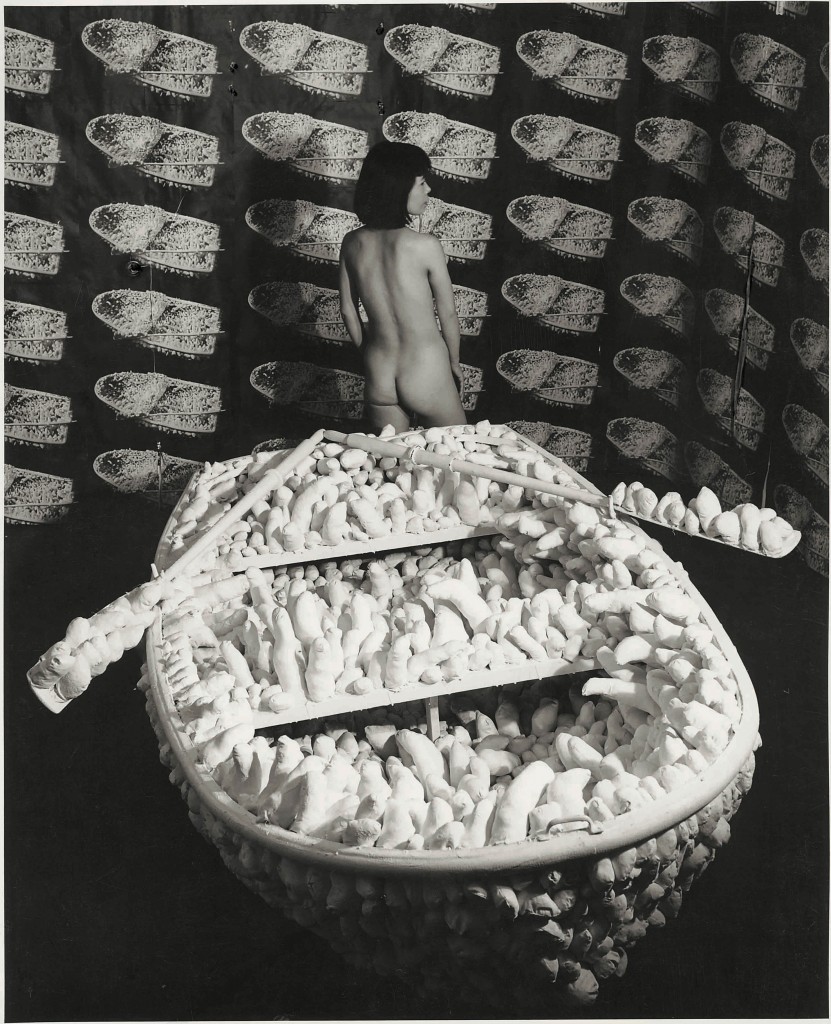

Obviously there are the phases in Kusama’s work covering her earliest Art Brut – style paintings and abstract watercolours of the 50s, her pioneering minimal explorations Infinity Nets and those famous phallic Accumulations of the 60s. Following a foray into collage and film at the same time as of her reactionary ‘happenings’ occurring in the psychedelic 70s, one can see other past motifs return to her work. Collage and watercolour resurfaces after her return to Japan and subsequent voluntary institutionalisation in 1973. The spermatozoa and natural forms of her earliest work return in her acrylic paintings in the 80s and by the 90s her fascination with organic abstraction extends into larger-than-life install pieces of stuffed cushions. The polka dots remain throughout.

Beyond her work, though, the Tate retrospective offers vital insight into the cultural and historical changes Kusama experienced in her over 60 years as an artist. Informative didactic panels and paraphernalia showcases contextualize her work brilliantly. A complaint of the “feudalistic attitudes” and “scorn of women” apparent in Japanese society introduces Kusama’s early gouache pieces, while her struggle with the “double outsider” status –as both foreigner and woman in the male-dominated New York art scene –is expressed through a slide projection featuring Kusama dressed in a kimono and in stark contrast to her urban-industrial backdrop.

There are display cases of letters and correspondence from various galleries, plane tickets and promotional material that construct an image of the times and Kusama’s place in them. A note from friend and artist Georgia O’Keefe sits aside a memo from Orez Gallery in the Netherlands stating they will cover Kusama’s costs in return for some artwork (for much of her time in New York, she was nearly destitute). There are numerous exhibition statements from the artist herself explaining her practice in very detailed, lucid and, importantly, determined language.

In much the same way that time adds value to photographs and architecture, so does it add importance to Kusama’s work and related ephemera. The plane ticket she used to cross the Pacific Ocean from Japan to the US is loaded with as much historical significance as her repetitious collage of airmail stickers from 1963, while the publicity from her Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead almost makes up for not being able to see the real thing. But in all the ways that Kusama’s work and private keepsakes evoke and transport one to days gone by, nothing compares to her Infinity Room expressing how it feels to be in a mind afflicted by madness and the burdensome perception everlasting time and endless space.